Summary of this article

In a petition to the Supreme Court (SC) in 2019, the mothers of Rohith Vemula and Payal Tadvi,for strict implementation of the 2012 UGC regulations.

Scientific classroom teaching, including the development of skill and capabilities to deal with diversity, through specially designed courses is necessary.

NEP 2020's course drew moral values from all religions, human rights and the Constitution, in practice the course mainly draws moral values from Brahmanism such as the Vedas, the Upanishads and the Smritis, including Manusmriti.

The University Grants Commission (UGC) had framed the UGC (Promotion of Equity in Higher Educational Institutions) Regulations, 2012, with a goal to eliminate discrimination and promote social inclusion in higher education campuses. In a petition to the Supreme Court (SC) in 2019, the mothers of Rohith Vemula and Payal Tadvi who lost their children had asked for strict implementation of the 2012 regulations. In response to an advisory by the SC, the UGC brought out an improved set of regulations in January 2026. However, a section of general category students expressed dissent over some provisions of the regulations. Responding favourably to the arguments, the SC kept the 2026 regulation in abeyance and ordered its review for it believed that the provisions were vague and capable of being misused.

The petitioners primarily expressed opposition to the separate mention of “discrimination only on the basis of caste or tribe against the members of the Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes, and Other Backward Classes”. They asserted that there was no need to mention caste discrimination as it would be covered under the general definition of “discrimination”, which includes all forms of discriminatory treatment, including caste. They also argued that a separate mention of caste may result in division on campuses. Apparently, this argument by the petitioners is not justified. Although there is a similarity in the nature of discrimination embedded in caste/untouchability and those associated with gender, religion, race, colour, the former is unique and special. Therefore caste/untouchability-based discrimination, besides being made a part of general discrimination, also needs to be mentioned separately. Besides, the 2012 regulations have been in operation for the last 11 years, and they have not resulted in division on the campuses or misused.

However, there are a few important missing links in the 2026 Regulations. The 2026 regulations proposed a dual strategy to eliminate discrimination and to bring equity and social inclusion. First are safeguards for a person who faces discrimination through necessary action against the discriminator in the form of civil punishment. The second strategy is sensitising students to bring about an attitudinal change to prevent discrimination through measures that include furnishing an undertaking at the time of admission to promote equity and not to indulge in any form of discrimination. These include orientation lectures by the Head of the Institution at the beginning of the academic session, holding workshops, displaying posters on the campus and other events.

The missing link in the strategy for sensitisation is that it does not go for an “unlearning” of the prejudicial values that students carry with them and imparting the right value of non-discriminatory behaviour. It has to be recognised that the massification of higher education has brought in diversity in student composition. In 2018, the student population composed five per cent Scheduled Tribes (STs), 14.86 per cent Scheduled Castes (SCs), 37 per cent Other Backward Classes (OBCs), 27 per cent upper castes, 9.63 per cent Muslims, 2.67 per cent Christians and about three per cent Sikhs/Buddhists/Jains. Along with the diverse social belonging, the students carry with them values and ideas, which are often prejudicial and discriminatory against other groups. Diversity brings social grouping involving discriminatory attitudes against Dalits/Tribals/ OBCs, women, Muslims/Christians and students from the Northeast, based on caste, gender, religion and race respectively. There is significant evidence from studies that discriminatory attitudes result in a social divide in classrooms, laboratories, hostels, messes, cultural functions, sports, clubs and friendships. In the case of Dalit and Adivasi students, it involves humiliation, and contempt, which is demeaning and undermines the dignity of students.

What is required is scientific classroom teaching, including the development of skill and capabilities to deal with diversity, through specially designed courses.

These negative attitudes and values are built up among students in early stages through socialisation in the family, caste/religious association and through societal interaction. Therefore, what is needed is the “unlearning” of the negative values of inequality, restrictions related to food and dress, apart from anti-social behaviour involving contempt—sometimes coercion and violence. Orientation through written undertakings about non-discriminatory behaviour, lectures, posters and workshops for sensitisation may have some impact, but will not “unlearn” and remove the values of treating “others” unequally and differently, restrictions, non-fraternal, and non-compassionate attitude, which are built over a long period of time through socialisation in the family and in interactions with society.

The limitation of the sensitisation strategy is that it does not involve systematic classroom teaching on moral education. Besides, it does not expose the student to the real situation. What is required is scientific classroom teaching, including the development of skill and capabilities to deal with diversity, through specially designed courses. It requires a conscious effort to build values of equality and equal opportunity, non-discrimination, individual freedoms, fraternity, compassion towards others, and a collective well-being of self as well as of others.

When educational campuses in the US department got diversified from white-only students to mixed-women—Black, Latino and South Asian students—the education ministry asked the Association of College and University teachers to inquire into the linkages between diversity and discrimination. The report, which was submitted in 2000, recommended a special course named “Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement”, which was made compulsory in many universities. It includes themes such as poverty, inequality, racism, colourism, religious prejudice, feminism, elitism, and classism. Under democratic engagement, it involves visits by white students to Black localities to personally experience their life. It also involves new pedagogical methods, in which face-to-face group discussions are held among white, Black, Muslim, Christian, Jew, Hindu, Latino and south Asian students to understand each other’s religious values and develop tolerance and positive attitudes, replacing stereotypes and prejudices.

For the Indian education system, panels from the first Education Commission in 1882 to the Radhakrishnan Commission, 1948, and the Kothari Commission in 1965, down to the Kasturirangan Committee in 2019, have recommended “moral education”, but no systematic steps were initiated. The National Education Policy, 2020, did suggest a course on moral education—a “Mulya Pravah” for higher education and “moral value and disposition” for school education in its curriculum framework of 2023. Though it pretended to draw moral values from all religions, human rights and the Constitution, in practice the course mainly draws moral values from Brahmanism such as the Vedas, the Upanishads and the Smritis, including Manusmriti.

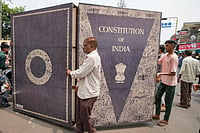

What we require is a special course based on the values etched in our Constitution—the values of democracy, socialism, secularism and national unity, which form the governing principles of our nation. Also, it should contain the fundamental rights of equality to all, liberty, fraternity and humanity. It should also include the duties of citizens, and the cultivation of scientific and rational temper among students. It must include the ideas prescribed in the Directive Principles of State Policy, which requires the State to develop policies for social justice and equality. The Karnataka Commission on Education 2024-25 has recommended a compulsory course on “Constitutional Moral Education” for higher education students. The student is required to undertake this course at least once. Similar courses on moral education are proposed for schoolchildren.

A review of the impact of the course, “Civil Learning and Democratic Engagement” in 2011 in the US—10 years after its introduction in 2000—in a “Crucible Movement Report” found a positive impact on the character and personality of students, including academic performance. The Union government should incorporate such courses in the UGC regulations for all Indian education institutions to build the character of students to transform them into good citizens.

(Views expressed are personal)

Sukhadeo Thorat is the former chairman, UGC