As Uttrakhand goes to polls on Monday for its 70 assembly seats and decides the fate of Chief Minister Pushkar Singh Dhami, one of the striking, rather alarming highlights of the crucial election this time will be the complete absence of poll activity in 1,564 “ghost” villages.

No EVMs were randomised, no polling booths set up and no polling parties deputed for the villages, which are completely abandoned. The entire population of 1,564 Uttrakhand hill villages has migrated to big cities for multiple factors, notable ones being lack of development and employment.

There are other 650 villages, which are also left with a population of less than 50 percent, thus all these villages are now called “bhootiya villages” or Ghost villages of Uttrakhand, a state formed in 2000.

Even as the poll activity in the state generated heat with BJP, already in the power for the past five years, boasting about development, the issue of migration remained almost overshadowed. The ground realities, however, can alarm anyone traveling to the state to get a sense and meaning of the elections for the poor hill population.

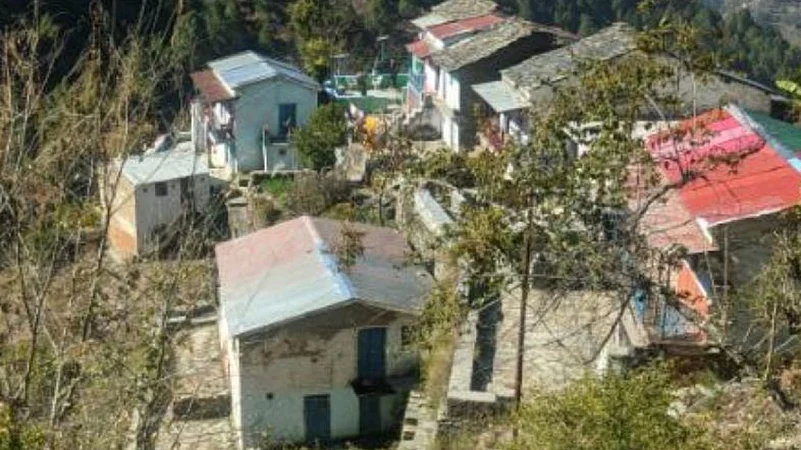

In Pauri Garhwal -- a district with six assembly constituencies, there are 180 villages with zero population and 300 others that are partially inhabited. The houses are abandoned, crumbling and wild bushes and shrubs growing all over the spaces. Not even a single human soul in sight, in and out, for years.

Collector Pauri Dr. Vijay Kumar Jogdande admits that no polling parties have been sent to these ghost villages where there is none to cast votes. This is definitely a picture of contrast in the election time in the hill state.

On reasons of migration, he says “There are multiple factors. Almost 50 percent left for lack of employment opportunities, 16 to 17 percent due to non-availability of education or schools and other 10 to 12 percent health facilities not being set up. This is a big problem indeed”.

The Migration Commission set up by the former Uttarakhand Chief Minister Trivendra Rawat to study an alarming problem of out-migration in the state has confirmed a mass exodus from the villages, mainly the districts like Pouri Gharwal, Chamoli, Almora, Tehri Garhwal, Rudraprayag and Uttarkashi. All these are districts lack basic facilities, prominent of these lack of employment, roads infrastructure, health care and education.

This has not left unaffected Radha Balabh Puram, the native village of former Uttrakhand Chief Minister BC Khanduri, where only five to six families live now.

Migration commission Vice-Chairman, SS Negi says, “More than 1.19 lakh people have left their villages in the past one decade. There is a striking 50 per cent of them deserting their villages only in search of livelihood. The others because of poor education and health facilities. Some of them have migrated out of compulsions and in distress, rest voluntarily migrated moved from one part of the state to another for jobs, education of their children and caring for better health facilities in the towns”.

He also underlines the point that there is a huge imbalance in the development priorities in the plains versus hilly districts.

In Kot block of Pauri, 20 km from the district headquarter, village Boundil has already attained the notoriety of sorts with just a one-woman Bimla Devi, 71 left to live in the village that had 60 to 65 families. It was only during the Covid pandemic that two other families returned.

“There is no transport facility in the area. No roads were built. We have to climb a high mountainous path, which is marked by the growth of wild bushes, plants and creepers. Several times, I got confronted by leopards and wild animals while escorting my daughter to a school 6 to 7 km treacherous walk. Almost all families have left because of the everyday struggle to survive and earn their living," Dheeraj Kumar Juiyal says as he points to locked and deserted houses.

The worst affected villages are in two blocks Kaljikhal and Kot. Another two ‘ghost villages’ are Gaundli and Kagadi in Khirsu block,15 from Pauri with 100 percent migrations. Baluni, a village in Kaljikhal block, once a hub of agriculture activities and green fields, has turned barren with none to cultivate the field. Locks in some of the houses clearly show no human activity. Houses are broken and roofs collapsed. Wild animals can be seen roaming during the day.

Says Bhaskar Bahuguna, a social activist who works on livelihood matters for rural communities,“ The people are deserting their villages not only to look for livelihood means but survive. The areas are highly underdeveloped, with no road facilities, no health care and no schools for children. Moreover, there is also a threat of wild animals invading these villages. If people don't find themselves safe, they will not live”

The 2011 Census listed 1,053 such “uninhabited villages” as “ghost villages'' while the Migration commission‘s studies have put the number of such villages at 1564 as of January 2018 while another 650 have their population reduced to below 50 per cent.

Between 2001 and 2011, Pauri district registered a negative population growth of -1.51 percent as Almora, reflecting -1.73 percent. Yet in contrast, the districts of Dehradun, Udham Singh Nagar and Haridwar have shown a population growth of 32.48 per cent, 33.40 percent, and 33.16 percent respectively. These are districts with better amenities and a lot of job avenues.

“A huge chunk of people from hills migrated to these districts as also places like Gurgaon, Bhopal, Lucknow, Delhi, Mumbai and Chandigarh. They built their properties and never returned. Yet few families do visit for religious rituals and ceremonies in their villages but not to live,“ Bhaskar Bahuguna explains as his own village Kothar—one of the biggest villages, now left with just five-six families though barely six to seven km from Pauri.

There are no categories of people migrating. One those having got education, selected as civil servants, engineers or businessmen. Others look for jobs as migrant workers outside the state or get employed in the private sector.

Village Sumari, a village with the highest literacy ratio of 80 percent has several IAS officers and successful businessmen but is left with less than 50 percent population.

Bhagwad Sein valley, known for best agricultural produce has turned barren as no one is inclined to stay in the village for lack of basic facilities – roads, health care and education.

"But has this become a poll issue," says Rajesh Dharmani, who is AICC in charge in Uttrakhand. He adds, “It’s certainly an issue which the new government has to address on priority. Migration of course is a big issue as primarily it’s related to lack of employment and development. There are 57,000 vacancies in the government sector alone. No development has taken place in the districts of Pauri, Almora, Chamoli, Pithoragarh and Uttarkashi. Naturally, the villages have no one living to die. It’s the instinct for survival."