This article was published in the Outlook magazine issue 'Emergency: The Legacy/The Lunacy' dated October 1, 2024. To read more article from the issue, click here.

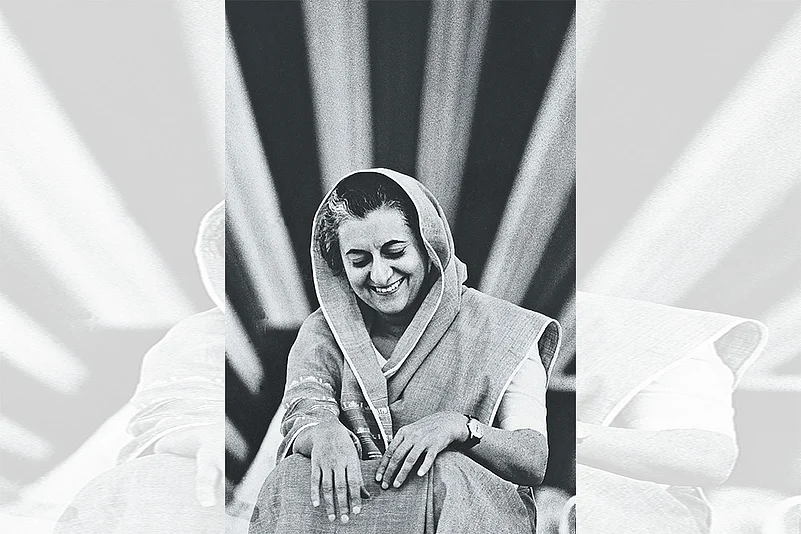

If Prime Minister Narendra Modi completes his current term in office, he will exceed Indira Gandhi’s term in office by a few months short of a year. During the past decade, Modi has never missed any occasion, never let slip the slightest opportunity, to denigrate her and glorify his government’s achievements during its rule over India. Indira Gandhi died in tragic circumstances more than 40 years ago. So for obvious reasons, she cannot defend herself. But that doesn’t mean that others can’t.

My entry into journalism in 1966 virtually coincided with her becoming Prime Minister, and by sheer coincidence, I was on Safdarjung Road on October 31, 1984, a couple of hundred metres from her home, when a constable erecting a barrier told me—his eyes red with grief and suppressed anger—that Indira Gandhi had been shot.

In the 17 years between 1966 and 1984, I commented upon her government’s policies and actions almost every day in editorials and columns in The Times of India. In the past 10 years, I have done the same with the policies of the Modi government in The Wire. Much of my writing in this decade has been devoted to correcting the warped version of our history and religion, and of Indira Gandhi’s rule that Modi and his digital army have been projecting. In what follows, I have looked back over those 17 years and tried to assess the validity of Modi’s criticisms.

When she came to power, Indira Gandhi had lived India’s politics all her life, but had absolutely no experience of administration. To make her task more difficult, she became the prime minister when our country was in a crisis. India had just suffered the first of two colossal droughts in 1965, and had been able to feed its population only because of the vast American wheat shipments under its Public Law 480. The passage of the Second Industrial Policy Resolution of 1956, which aimed to create a ‘socialist pattern of society’, had all but blocked not only private investment, but also severely limited the growth of existing industrial enterprises in the private sector.

In 1956, India was also in the middle of a foreign exchange crisis caused by the exhaustion of the foreign exchange reserves it had accumulated in London during the Second World War. This had forced the government to impose an almost total ban on imports. Finally, since domestic political pressure had forced the Jawaharlal Nehru government to ignore the World Bank’s entreaties to devalue the rupee in 1961, India’s principal exports, tea, jute and cotton textiles, had become increasingly uncompetitive. Therefore, when Indira Gandhi came to power, the country was nearly bankrupt.

Indira Gandhi had no administrative experience, but she was a nationalist to the core. So she took the decisions that both Nehru and Lal Bahadur Shastri had shirked, and devalued the rupee by a massive 57.5 per cent. This would have restored India’s export competitiveness immediately, had the US Congress not held up a $900 million World Bank transition assistance package in an attempt to force India to repeal its near-ban on private and foreign investment. The result was a sudden and extreme, shortage of manufactured consumer goods, which combined with a second consecutive drought in 1966, pushed wholesale prices up by 32 per cent in a single year.

The setback, however, was short-lived. The near-ban on imports created space for small enterprise-based industry to arise within the country. Therefore, industrial growth averaged nine per cent in the next decade.

The end of 1966 also saw the first fruits of the Green Revolution in wheat—production jumped from just over six million tonnes in 1965-66 to over 11 million tonnes in 1966-67. In the mid-1970s, the Green Revolution also spread to rice and, in the next half century, turned India from a chronic food importer into the largest exporter of rice and second-largest exporter of vegetables, dairy products and meat in the world today.

All this resulted from Indira Gandhi’s willingness to listen to advice from her Principal Secretary L K Jha on devaluation and from Agriculture Minister C Subramaniam on winding up cooperative farming in agriculture.

Indira Gandhi’s most historic decision, however, was to liberate East Pakistan from the grip of West Pakistan. Even here, true to form, she allowed Chief of Army Staff, Sam Manekshaw, to decide the timing of the liberation. Manekshaw waited until the torrential monsoon rains had ended and the ground was firm enough to support tanks, and ended the war in 16 days. Indira Gandhi used the hiatus to train the Mukti Bahini and, when the war began, ignored threats by the US to come to Pakistan’s aid, and its despatch of an aircraft carrier to the Bay of Bengal. India ended the war before the carrier arrived.

All of these paint the picture of a prime minister who owed her success to her respect for democracy, law and due process. So why did she declare an Emergency, and ‘postpone’ parliamentary elections for a year in June 1975? The popular belief, fanned relentlessly by the Sangh Parivar, is that Indira Gandhi did so in order to cling to power at any cost after an Allahabad High Court judgement of June 12, 1975, upheld by the Supreme Court, had found her guilty of having spent more on her election in 1971 than was allowed by the Constitution.

This is simply not true because Justice Krishna Iyer, who headed the vacation bench of the Supreme Court, had allowed her to continue functioning as prime minister without a vote in Parliament, till her appeal had been heard by a full bench of the apex court. Indira Gandhi took advantage of this and stayed in power to prevent a vacuum from developing at the epicentre of State Power, at a time when the country was sliding into chaos.

The slide had begun 13 months earlier with a student-led rebellion against Congress Chief Minister Chimanbhai Patel in Gujarat in December 1973. The catalyst had been a belief that Patel had manipulated edible oil prices to benefit family and friends at a time when Gujarat was in the grip of drought.

Indira Gandhi first tried to propitiate the students by making Patel resign, declaring President’s Rule, and putting the Gujarat Assembly in suspension. But this turned out to be a tactical mistake. Sensing weakness, the entire opposition—from the Communists to the Jana Sangh and the Congress (O) —joined the students and demanded dissolution of the Gujarat assembly and a new election. When Morarji Desai went on a fast to force the issue, Indira Gandhi, despite having 148 seats in the 168 seat assembly, again gave in and dissolved the house in March 1974.

This further emboldened the Opposition and, with the disciplined cadres of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and the Jan Sangh in the lead, turned what had begun as a legitimate expression of grievance into an illegitimate attempt to force regime change through coercion. Within days, the movement spread to Bihar. By June 1974, it had spread to Karnataka, Uttar Pradesh and Punjab. In his autobiography, P N Dhar, Indira Gandhi’s principal secretary at the time, says, “Nobody shed a tear for the demise of the rule of law and constitutional means of changing governments.”

Indira Gandhi had no administrative experience, but she was a nationalist to the core. So she took the decisions that both Nehru and Lal Bahadur Shastri had shirked, and devalued the rupee by a massive 57.5 per cent.

The turning point was the assassination of Railway Minister Lalit Narain Mishra in Bihar on January 3, 1975, the first such political assassination since that of Mahatma Gandhi. Five days later, Siddhartha Shankar Ray, the chief minister of West Bengal, wrote to Indira Gandhi that the time had come to restore order through the declaration of a national Emergency.

Indira Gandhi still did not do so. Even the Allahabad High Court’s judgement did not persuade her. It was only when Jayaprakash Narayan, one of the last and most respected stalwarts of the freedom movement, advised the police not to obey orders to arrest demonstrators, that she finally changed her mind.

But she had no intention of extending the Emergency, let alone of abolishing democracy. After the fateful early morning Cabinet meeting on June 26, K C Pant, one of her most trusted and liked Cabinet ministers, asked her pointedly whether she was really postponing the next parliamentary elections for only one year. “When I asked her this”, he told me several years later, “She was irritated and replied abruptly, ‘…of course, this is only for one year. To extend it further would destroy democracy’.”

This was confirmed several years later when Dhar, Indira Gandhi’s longest-serving and most trusted principal secretary, published his memoirs. He disclosed that when the IB informed her that their surveys showed that the Congress would win only 153 seats, Indira Gandhi’s son Sanjay, and two of his closest advisers, had urged her to extend the Emergency for another year. Her reaction was to cut Sanjay out of policy meetings for the next three months, until she had announced the date for the elections in January 1977. Indira Gandhi went into that election knowing she would lose. Would Modi have done the same?

In her long tenure, Indira Gandhi also made her quota of mistakes. Her first and most serious was the banning of corporate donations to political parties after the Congress’ near defeat in the 1967 elections. Though Lok Sabha constituencies are 6,000 square km in size, as opposed to 370 square km in Britain, the Constituent Assembly, in its ‘unwisdom’, did not consider it necessary to create a national election financing system for the country. By 1962, this had begun to create problems even for the Congress, so all political parties had turned to the corporate sector to meet their needs. To encourage this, the government had exempted donations to recognised political parties from taxation.

By 1967, however, companies were no longer giving donations only to the Congress, but also in increasing amounts to the newly-created, industry-friendly, Swatantra Party, which, to make matters worse, had teamed up with the Jana Sangh. In the elections that followed, not only did the Swatantra Party emerge as the second-largest party in Parliament, but the combine wrested four state governments from the Congress.

The Congress party panicked and asked Indira Gandhi to ban company donations to political parties altogether, arguing that the Congress could always raise the sums it needed by twisting the arms of the industrialists. Indira Gandhi agreed and enacted the ban in 1970. Since money was still needed in growing amounts, this not only criminalised the entire political system, but also gave the Modi government the weapon, in the form of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA) that it is using to destroy the Opposition today.

But the mistake that has had the most long-lasting effect on Indian politics was, to a large extent, forced upon her. This was the split in the Congress in 1969, even after V V Giri, Indira Gandhi’s candidate for the Presidency of India, had defeated N Sanjiva Reddy, whom the Congress organisation had fielded against Giri. The split proved to be fateful because it converted the Congress from a party that ruled through consensus between powerful regional leaders, as it had been since 1885, into one ruled by a single leader, a supremo. Today that structure, and the sycophancy it has bred, has become the principal obstacle to the creation of a durable alternative to the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

Nothing demonstrates this better than the Congress’ decision to steamroll Rahul Gandhi’s Bharat Jodo Nyay Yatra through Bihar, over the strenuous objections of its chief minister and key INDIA bloc member, Nitish Kumar. Had Rahul Gandhi and his advisers heeded Kumar’s request, the INDIA bloc would have been in power today, and Rahul Gandhi may well have been the prime minister of India, instead of lecturing the diaspora in the USA.

(Views expressed are personal)

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Prem Shankar Jha is a columnist and author residing in Delhi