Be it Salman Rushdie, AK Ramanujan or any other author who has upheld the sanctity of progressive thought through their writings, no one has ever been lauded, rather, accepted for their works. The religio-political stance of the likes of Rushdie and Ramanujan has always challenged the deeply entrenched stereotypes and conventionalities of religion and has subsequently been viewed through the narrow lens of the so-called modern society. The lethal attacks on Rushdie and the removal of Ramanujan’s essay from the syllabus of one of the top universities of the country have been proofs that if rationality and wisdom find a voice, they are surrounded by the cacophonies of irrationality and fanaticism to drown that voice out.

And then to add insult to injury, some authors are born women. The part they play in shaping public consciousness towards literature is deeply connected to their feminine identity.

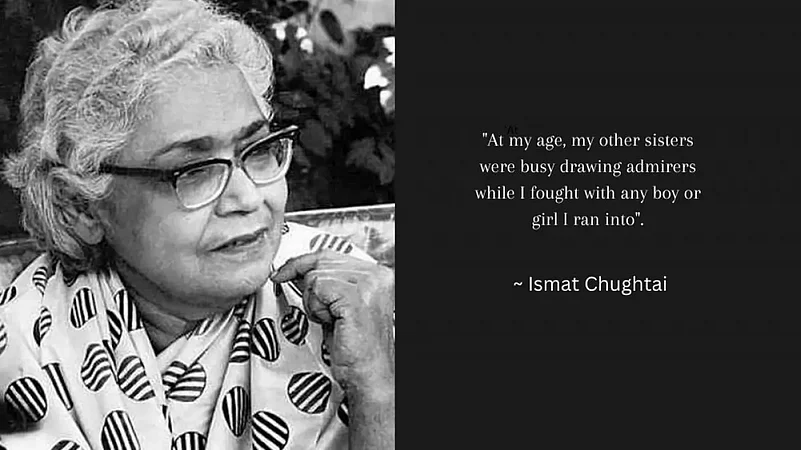

One such author was Ismat Chughtai, endearingly called Ismat Apa by many of her admirers.

Fame and Notoriety

Ismat’s life and works reflect the changing paradigms of literary culture. Ismat Chughtai was an author of the Urdu language. She was born in a liberal Muslim family on 21 August 1915 in Badayun, Uttar Pradesh. Her stories are mainly about the lives of women she saw and met with in her everyday life. The characters of her story emanate from how she relates to and perceives the women around her, who cut across class. While in one story the protagonist is a wealthy lonely begum, in another the limelight is on an energetic chirpy domestic help.

Chughtai began writing from an early age but her works were exposed to the public from the 1930s onwards and the canvas of her writing kept expanding and influencing critics and connoisseurs till the 1960s-1980s. The author remained a centre of controversies for several years and attracted both notoriety and fame with the changing times.

For Chughtai, notoriety came as the instant result of the exposure of the public to one of her stories when she wrote it and the same story brought her copious amounts of fame when several years later, it was seen as a ground-breaking work of her times. The modern literary public has also had a meandering trajectory when it comes to embodying the openness for modern thought.

Lihaf is one of Chughtai’s most popular stories. Written in 1942, it is about a neglected wealthy begum who develops a sexual desire for her masseuse and the co-exploration of their desires together. This particular story created quite a flutter in the times that be. Not only did Ismat Chughtai draw flak from the so-called sophisticated echelons of the then society but also from the court. She was summoned by the Lahore Court in 1944 and thrashed for producing an obscene work. But Ismat stood her ground, saw through the judicial process and was acquitted.

In the present times, Lihaf has been cited as an exemplary work by many activists for LGBTQI rights and Chughtai has been seen as an advocate of such rights and desire among women.

Reception of her works

What becomes interesting to note is that a literary public who was reading Chughtai’s work was and has not been a monolith. While the middle-class public and the Lahore Court looked down upon the story, the woman about whom the story was, drew strength from the story on reading it and took a bold step in her life. The present-day activists draw solidarity for their cause from the story and so the reception of the story by different sections of the society at different points of time has been varied.

Another intriguing work of Chughtai is Gharwali. It is a story of a single man who is attracted to her domestic help and ends with him consummating his relationship with her. A strong theme of the story is sex – a hushed-up topic even today. Many of Chughtai’s stories deal with taboo subjects. An important consideration here would be, was the then public ready to read about taboo subjects in literature. And if not, were Chughtai’s works opening them up to taste different flavours. It is then that one can try to unravel, whether the author was building a public with a literary consciousness or there already existed a literary consciousness among the public which was smothered and bolstered by the works of Chughtai. However, one can say with confidence, that Chughtai was writing fearlessly and the might of her pen was and has been making forays in the unknown territories of literary culture in India.

Influence of the social milieu

A milestone moment in understanding the social mores of the times in which Chughtai lived can be her joining the Progressive Writers’ Association in 1936. Several celebrated authors of the time, including Sadat Hasan Manto were part of the association and it is amply clear that the groundwork for exposing the public to new liberal ideas, breaking away from a conservative way of living, was being done. The currents of progressive thought were already rippling in the then society and the Progressive Writers’ Association was a step towards consolidating it. Manto, one of Chughtai’s greatest friends, and Chughtai together, had to bear the brunt of a tumultuous trial when the too “progressive” writings of these authors came under the atrocious scrutiny of the then public. Their writings were badged as obscene and seditious, and it was demanded that they be scrapped. It is important to note here that what had been called obscene were deeply political and socio-political commentaries on the society written in a manner that was bitingly sharp, and nowhere near to hurting sentiments.

As far as the bigger picture of the country and its influence on shaping brave authors was concerned, there occurred religious riots in Bombay in 1936, the civil disobedience movement was on and there was the proclamation of temple entry by Dalits in Travancore. The country at large was moving towards a more progressive station and this was reflected in the way rational and progressive thought was finding its way through the works of the writers of the time who were thinking and questioning the status quo.

Chughtai’s feminism

Themes of feminism and femininity have dominated almost all of Chughtai’s works. Her novels and stories have strong female characters who are often rebellious and deviant just like she was. This has not only contributed to the vast pool of feminist literature in India but has also established that waves of feminism were not just confined to non-literary writings during those times. If several women across different sections of society were responding to the call of Gandhi, there were many who were asserting their participation in society through their pens, one of which was Ismat Chughtai.

Adapting to the changing times

With the passage of time, Chughtai moved on to write plays, screenplays and made films too. She was adapting to the changing times while also keeping up with what was in vogue. It is not that only the commoners were influenced by Ismat Chughtai’s works but a number of other present day litterateurs have absorbed many of Chughtai’s works into their own renditions. Naseeruddin Shah adapted the works of Chughtai in a play called “Ismat Aapa Ke Naam.” It is an anthology of her stories and Shah’s daughter was the lead actor in the play. Short story writer and critic, Aamer Hussain, appreciated Chughtai’s stories by saying that she never shows or explains through her prose, infact it is studded with poetic observations like that of American author Toni Morrison. Chughtai in one of her works named Ajeeb Aadmi written in 1970, discusses about the extra marital affair of a popular Bollywood figure. Remarking on this particular work of Ismat Chughtai, author Jerry Pinto once said that the way she wrote about the convoluted personal lives of Bollywood players was unprecedented.

Several of Chughtai’s works have been translated into Hindi and English, widening the reach of her stories to a larger readership. A whole new contemporary literary culture has been created out of Chughtai’s works that were written in the past but are on issues that are omni-present and ever so timely.

Ismat Chughtai is a resounding voice in literature in India. She once said that she does not want to be buried after her death as burial is suffocating. She wanted to be cremated instead. Upon her death on 24 October 1991, she was cremated in Bombay.

Her life and works have influenced a kind of people that comprises of commoners, critics, connoisseurs, men, women, children, adolescents, activists, feminists and anybody who wants to understand what fearlessness in thought and writing is, from a woman’s perspective.

(Malvika Sharad has previously worked with the Economic and Political Weekly. View expressed are personal)