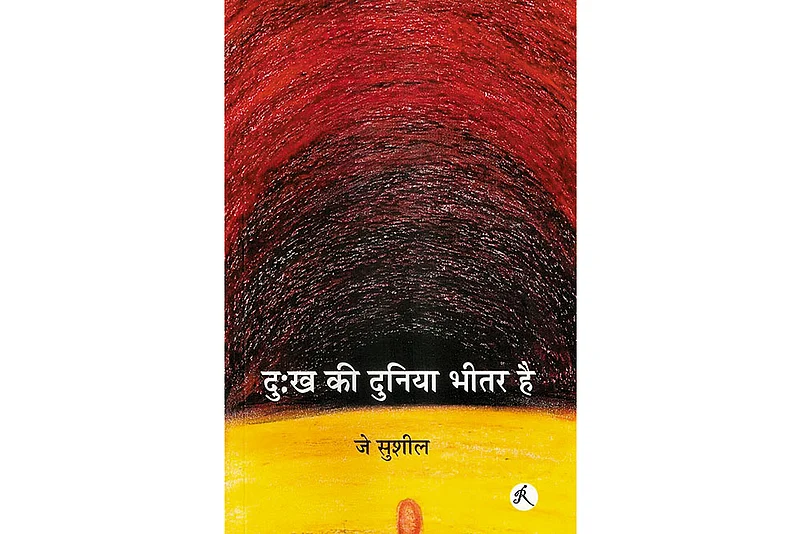

Sushil's life shaped by the ideals of industrial India—the “temples of modern India”— where one could hope to build a secure livelihood and a better future for one’s children

The book begins with the father’s return to his ancestral village after retirement, carrying the hope that he would spend but he is not excepted.

The second portion of the book shifts to Jadugoda, where Sushil was born and raised.

At its core, the memoir is the story of Sushil’s father, a man born in a small village in Bihar, who spent his life working in the uranium mines of Jadugoda, Jharkhand. His was a life shaped by the ideals of industrial India—the “temples of modern India”— where one could hope to build a secure livelihood and a better future for one’s children. But by the end of his life, those hopes had given way to the quiet despair that has touched so many workers in liberalised India. Written from the son’s perspective, the memoir opens with the shock of loss and slowly threads together fragments of memory to recount the life of his father and the larger family journey.

The book begins with the father’s return to his ancestral village after retirement, carrying the hope that he would spend the latter years of his life in the place where he was born. But the village refused to accept a man who had, in many ways, become an outsider. Petty self-interest, property disputes, family quarrels, and the relentless financial demands of relatives created a climate of alienation. The same village the father had left in his youth in search of work now offered only estrangement in his old age.

The second portion of the book shifts to Jadugoda, where Sushil was born and raised. Here, his father is a mine worker, and the township itself symbolises a generation’s faith in collective labour, the dignity of public-sector jobs, and an ethic of honest aspiration. Sushil paints a novelist’s picture of this industrial colony: uranium mines and factory sounds, trade unions and strikes, the sweat-soaked clothes of men returning from a day’s hard labour, and the faint, pungent odour of machine oil clinging to their bodies. Gradually, the memoir becomes a full social chronicle of an ordinary working-class Indian family. Through the lives of his father, mother, and three siblings, Sushil also comments on the condition and direction of Indian society: an elder brother’s inter-caste love marriage and the tensions it provoked, a middle brother’s broken home, and his own departure to faraway cities and foreign lands. Each episode carries the texture of lived experience, shaped as much by the tides of time and society as by individual choice.

Sushil’s style is both observational and autobiographical, marked by brute honesty. He writes as if sitting across from the reader, unafraid to open his heart, to speak the most inconvenient truths. He avoids artificial ornamentation of language, but still, the emotional undercurrents run deep in the whole narrative. There is no false colouring of grief, no self-glorification, and no melodrama. One of the book’s great strengths is its emotional restraint: Sushil describes deeply personal moments in a measured voice. Sometimes, even the most poignant scenes are rendered in an almost flat tone. For example, when he hears of his father’s death, he describes it without drama—just a quiet, growing pain that slowly seeps into the reader’s heart, like steady rain. A long career in journalism might have shaped his writing style. He often writes as a witness, an observer with the objectivity and clarity of someone reporting from the scene. This is why his depictions of Jadugoda’s social life, the factory atmosphere, his father’s co-workers, and the details of domestic life feel so vivid that they take the reader into the social milieu of Jadugoda.

Sushil writes openly about aspects of his family that many would leave unspoken: his father’s quick temper and occasional violence, his mother’s wasteful spending and domineering ways in household matters, and his brothers’ weaknesses. This unflinching honesty lends the memoir its authenticity. At times, he relies heavily on conjecture to enter his father’s mind—wondering why he acted as he did, imagining what he might have thought. This can give some episodes a repetitive feel, but it also reflects a son’s earnest desire to enter the inner world of a man separated from him by decades.

Some of the most memorable passages hinge on sensory memory: the smell of grease and oil from his father’s work clothes and the complex theatrical arrangements of the funeral feast, where the family and relatives seemed more concerned with donations and rituals than the human beings.

The episode of the elder brother’s life is particularly affecting. Defying the family to marry outside his caste, he provoked a rupture with their father. After leaving home, he drifted into addiction and eventually died in an accident. Sushil tells this story without drama, but this episode fills the reader with sorrow and grief. Apart from this, the memoir is shadowed by the theme of silence, especially that of the father. We see a man who was once a fiery union leader and a fighter for the oppressed retreat into a world of his own, a sort of shell, in his later life. The growing silence between father and son becomes almost a theme in its own right. One senses the son’s longing for conversations that never happened. In this light, the entire book can be read as an attempt to break that silence, to reach across time and even death to speak with his father.

This absence of dialogue, especially between a father and son, is a familiar feature of many Indian families, at least for the previous generation. Much remains unsaid between close relatives. After his father’s death, Sushil realises there were sides to the man he never fully knew; his spiritual leanings, aspirations, and failures remain partly a mystery. Like Michael Ondaatje in Running in the Family, Sushil reconstructs his father’s character through memories, fragments, and the words of others, and by the book’s end, we feel a quiet reconciliation taking place. Childhood resentments and unspoken grievances seem to melt in the warmth of mourning, and though his father is gone, the son has finally said what he wanted to say.

Of course, no work is without its limitations. For all its emotional authenticity, Dukh Ki Duniya Bhitar Hai is, by nature, deeply personal. It is, after all, the story of one family—rich with the names of people, the details of domestic disputes, and specific contexts that may not resonate equally with every reader. Those who have not experienced similar loss or familial dynamics may find certain episodes less compelling. A Dalit from rural Haryana, for example, might not relate to the elaborate death rituals that followed the author’s father’s demise; a tribal woman might respond differently to the theme of father-son relationships, silences, and unspoken words. Yet there is a common thread that binds most readers: the memoir’s emotional narrative. And these are minor shortcomings compared to the book’s strengths. The honesty with which Sushil writes, the balance he maintains between intimacy and detachment, and the way he transforms a family story into a work of social commentary make this memoir stand out in contemporary Hindi writing.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

(Ravinder Kumar is a Phd candidate in history at the University of Oregon)