Summary of this article

Binaca Geetmala turned radio into a national ritual, with Ameen Sayani’s voice uniting India every Wednesday night long before playlists or algorithms existed.

Built on listener postcards and public opinion, the show didn’t just play songs, it made audiences active participants and sharp judges of Hindi film music.

Through decades of cultural change, Sayani remained the constant, leaving behind a rare legacy of collective listening and genuine audience inclusion.

Before countdowns, playlists and algorithms told us what to like, there was a single voice that tuned an entire country to the same frequency. Every Wednesday night at 8 pm, India paused—mid-meal, mid-homework, mid-life—for Ameen Sayani’s Binaca Geetmala.

Much before digital music platforms were in vogue, Binaca Geetmala (named after the then popular toothpaste Binaca, manufactured by CIBA, the sponsor) played for a few decades on Radio Ceylon. It was a time when families huddled together around the radio, often making bets on the hierarchy of songs that would play out. Wednesdays came to be known as Geetmala day, and everything was planned around it.

The songs were chosen on the basis of a poll, with votes coming from all over and the build up to the last paydaan, as he called it, was nothing short of sensational. During its almost four decade run, Binaca Geetmala seeped into everyday life; the programme’s peak popularity years were the mid-1950s to late 1970s.

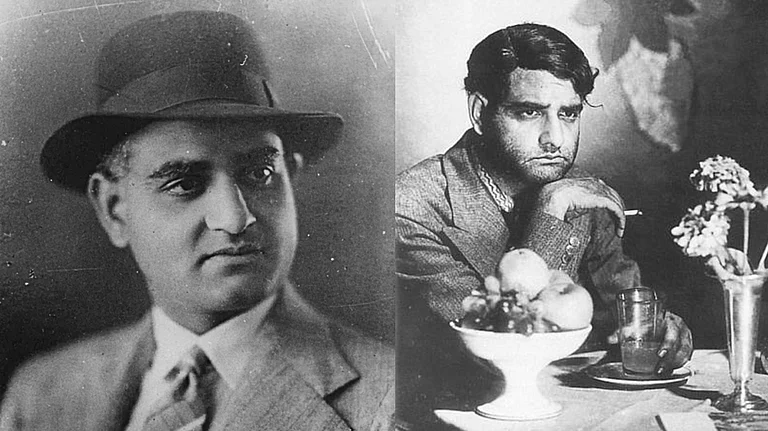

Ameen Sayani, who passed away in February 2024 at the age of 91, was arguably South Asia’s best known radio broadcaster, who greeted Binaca Geetmala’s listeners with a version of “Behno aur Bhaiyon….” recited in his characteristic upbeat style.

Binaca Geetmala was not just a family ritual, but a national one, especially at a time when Vividh Bharati had banned Hindi film songs in 1952, courtesy the then I&B minister B V Keskar. The programme ensured that every listener had an opinion about Hindi film songs’ overall merit and that sort of expertise in discernment of a song’s value became a popular pastime. The one hour programme became an absolute rage. Just like how the streets would be empty when B. R. Chopra’s Mahabharat (1988) or Ramanand Sagar’s Ramayan (1986) would be on television, the same happened with Geetmala, with everyone indoors, or even outdoors, at shops, nooks and railway stations, gathering around a radio or transistor.

Sayani listed 16 songs in order of popularity, the final one being introduced with a bugle, the build-up often dramatic, with edge of the seat vibes. The list was prepared on the basis of postcards received from listeners and responses came from every part of the country. He often picked out the odd postcard to read out; listeners became very familiar with names of places

they had never heard of before, such as Jhumri Talaiya and Rajnandgaon, among others.

The Limca Book of Records says Sayani has recorded over 54,000 radio programmes, which only goes on to demonstrate how integral he has been to the nation’s broadcasting journey—a part of the growing-up years of many generations who, through him, heard songs they wouldn’t have known otherwise.

In 1963, the immortal duet “Jo wada kiya woh nibhana padega” from Taj Mahal, sung by Lata Mangeshkar and Mohammed Rafi, earned the well-deserved #1 position in Binaca Geetmala and stayed on top for so long that the programme had to change its rules regarding the maximum number of weeks that a single song could be featured on the top of the charts.

As the years went by, the name of the toothpaste changed from Binaca to Cibaca and, then, after the company was bought over by Colgate, it became Colgate Cibaca Geetmala. Through all these changes, Ameen Sayani remained at the helm and effectively transformed ordinary radio listeners into opinionated and discerning Hindi film song experts.

Listeners took film song competition so seriously that many (including yours truly) kept detailed records of each week’s listings and often quizzed each other. Thursday mornings were important days for analysis and feedback. While many were elated that their song of choice was the sartaj, others rued that the postcards were rigged. What song would move up and what song would move down in the countdown was a crucial aspect of people’s lives and fodder for many arguments.

Public opinion became so important that the sponsoring company, CIBA, decided to create formal radio shrota sanghs, or radio clubs, which consisted of groups of people who would meet every week, listen to music in private homes or public spaces, vote for their favourite songs, and mail their choices to the company’s studios in Bombay. At the peak of the programme’s popularity, Geetmala had about 400 radio clubs.

Perhaps the greatness of Sayani lies not in how he began things but also the thought he left you with: “Agle saptah phir milenge, tab tak ke liye apne dost Ameen Sayani ko ijazat dijiye. Namaskar, shubhratri, shab-ba-khair!” Have we ever felt more included as an audience? I wonder.