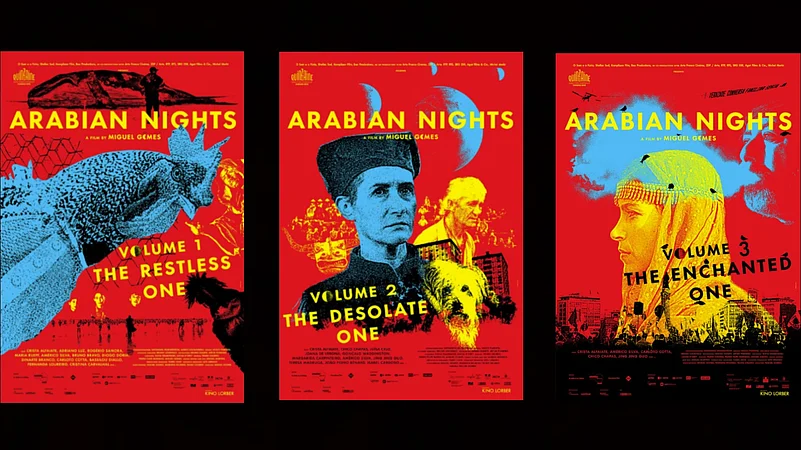

Miguel Gomes' Arabian Nights trilogy turns ten.

Fusing documentary and magic realism, the films take a playful look at Portugal rocked by recession.

The films premiered at Directors' Fortnight in Cannes 2015.

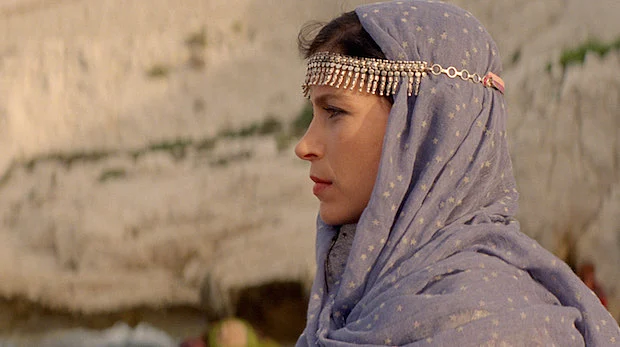

In Miguel Gomes’ three-part Arabian Nights (2015), Scheherazade (Crista Alfaiate) reminds us that the purpose of stories is “to bridge the time of the dead with the time of those to come.” While the princess in the original fable spun tales to prolong her life, Gomes uses stories as political reassertion. The direness of survival here is tinted with economic necessity. To re-energize, re-awaken his country Portugal clutching at straws, Gomes slides beyond docu-fiction in a patchwork of genres and subjectivities. Not just humans, animals and birds speak about this sad, weary, sinking land.

Community is at the center of this labyrinthine saga filled with detours, which we’re encouraged to get lost in. After all sorts of absurd, meta-theatrical experiments, the third volume chucks magic and observes a chaffinch trapper community with deliberate plainness. The conceit beneath it is remarkable. This is a group of people from very different backgrounds, bound by an obsession to train their chaffinches for birdsong competitions. These are Portugal’s impoverished working-class men, left with nothing but this to kill time. At every step in these films, Gomes flirts with the line between realism and fancy. He fights, as he himself puts it, the idea that we’ve to “evacuate the fictional” to talk about serious social issues.

Between 2010 and 2014, Portugal was plunged into its worst financial crisis. The government enacted a slew of austerity measures to dodge another international bailout. Salaries were cut, taxes spiked and unemployment surged. The social climate was stoked with layoffs and strikes. The cost-cutting didn’t pan out as intended, leaving an entire populace adrift. Gomes teamed up with few independent journalists for a year, who sourced stories and anecdotes from all over Portugal. These were presented to a “central committee” that combed out those best amenable to fabrication. In a ragtag way, Gomes sought to get the production off the ground. In the first volume, subtitled ‘The Restless One’, an official reprimands him, “The meagre resources of Portuguese cinema are incompatible with your reveries.” Early on, Gomes flees his own production. Nevertheless, this enterprise balloons beyond conventional wisdom. Over the three parts, the tone switches from that of bemused travelogues to farcical sketches to blankly observational treatises.

The trilogy owes a direct lineage to his earlier works, Our Beloved Month of August (2008) and Tabu (2012), in its constant emphasis on dramatized reality. Should we even see Gomes’ project as three separate entities or one, long unit? He withholds the answer. The worlds Gomes constructs defy containment within finite, pre-defined frameworks. Bursts of anarchic humor, sheer irreverence towards structure are primed as essential rebuttals to a government that has ceased to make any sense. Everywhere, there’s structural collapse. When citizens are hemmed in from all sides, what recourse remains but to scoff, advance their own dissident realities? Through plural, resistant narratives, Arabian Nights challenges an official, imposing truth. Gomes privileges no one dominant narrative or storyteller. Perspectives and terrain keep getting redrawn, renewed. Through the eyes of a dog happily shifting among owners, miseries of several depressed, financially down-and-out couples come forth. In interviews, Gomes stressed giving private reality the same consideration as collective, common reality.

In this, the films democratize responsibility and ownership, returning them to the regular working-class strata—the disenfranchised. Aesthetically, this entails embracing being messy, fractured, imperfect. At times, Gomes favors mobilizing unrest and anger, like among the dockworkers in Volume 1 swindled by their own country. The critiquing doesn’t baulk at going after the nexus of government and massive corporations which tramples all and weaves extortionist webs.

Working with a sprawling canvas, cinematographer Sayombhu Mukdeeprom isn’t fussy in propping up multiple tableaux. Yes, there are lush, sweeping shots of landscapes, bejeweled fineries. At times, the camera is just content to soak in the still, resting beauty. However, this is also promptly interrupted by rugged, verite impulses. Shot on both 16mm and 35mm, the films keep re-adapting, tonally and visually, to every discrete narrative leap. A bright, dazzling light streaks through it all. Much of the unique pleasures in Arabian Nights stem from Gomes’ dilemma. As much as he is besotted with the beauty and lavishness of royal chambers and accoutrements, Portugal’s ugly reality also insists.

In the second volume, ‘The Desolate One’, a judge gets overwhelmed to tears as every case folds into another. Everyone in the audience is exposed as complicit, with the country’s economic situation pushing all to desperation. No singular indictment becomes possible; rather, an entire system comes under the fray. In this chapter, the most overtly political in the saga, public disaffection is allowed to clamor out. Times are so dire that a social services functionary pretends to be homeless on TV to extract money. The judge tries to be furious but ultimately cedes defeat. She can no longer work out an individual solution. Exertion of State violence is felt throughout the trilogy, forcing a settled resignation among all. Authorities that are supposed to preside over and bring rational correctives are shown incapacitated. Justice cannot exist in such a skewed system. Ruthless poverty has rendered criminality all but natural. This somber proscenium-style open-air courtroom scene also incorporates burlesque elements. Peculiar demonic masks adorn few faces, while fugitive cows testify their own injustices, questioning the country’s terrible roads.

Throughout Arabian Nights, seriousness is undercut with surreal jolts. The first installment dips into ribald satire with a segue on austerity-imposing bankers afflicted with impotence. They are promised relief if they lift measures. Then, there are the unemployed citizens being interviewed by a trade unionist, juxtaposed with a beached whale that explodes.

Gomes is aware this unashamedly ambitious endeavor risks serious bloat. There are times when you feel he’s playing with the material just for the sake of it, caught in an aimless self-proclaiming loop. But he pleads that we put full faith and commit to the long haul. In a 2015 interview with Film Comment, Gomes emphasized, “We cannot renounce fiction, the possibility of saying things in very different way.” To cling to a homogenizing vision would be to fall in line with the establishment. Hence, the triptych’s scattershot impulses, occasionally frustrating, should be seen as retaliatory forces. Just the bewilderment of the visions the films dole out far supersede flat, predictable templates rife in cinema. Gomes’ magnificently disobedient storytelling has the gospel force of the best dissident art. Listen keenly.