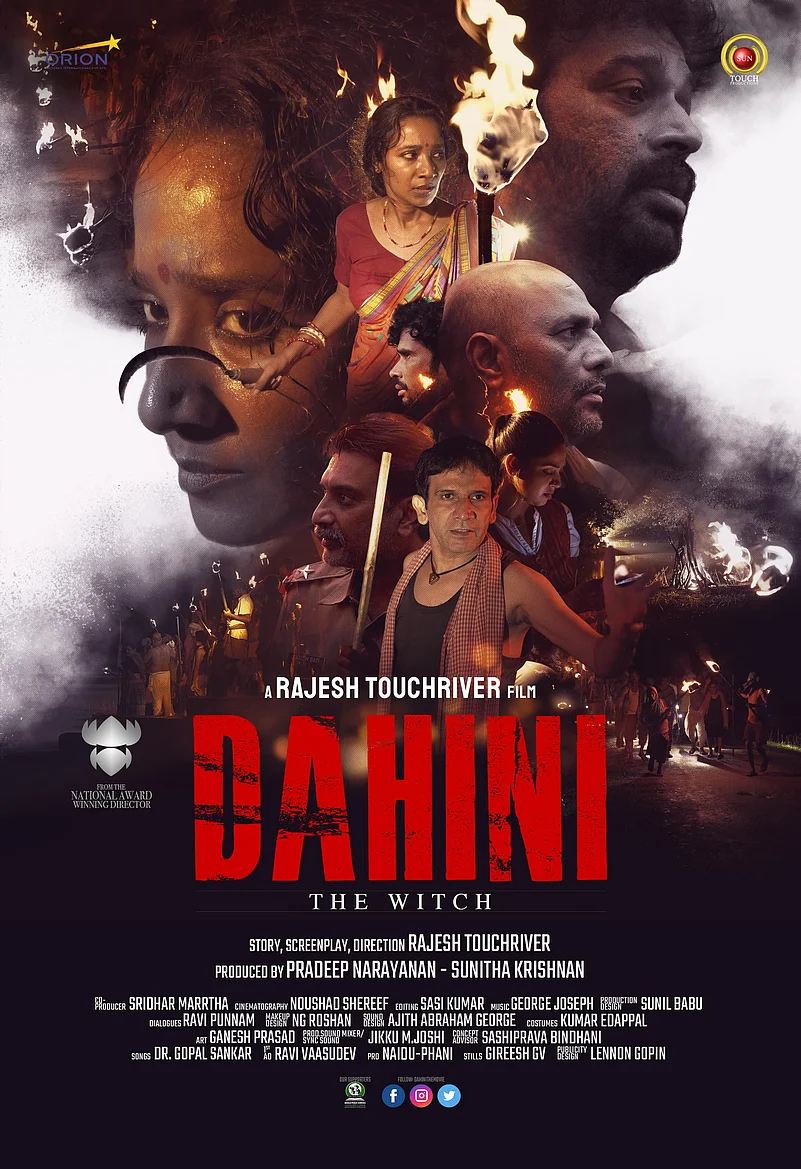

Rajesh Touchriver’s Dahini: The Witch (2023), which is being screened at the Indian Film Festival of Sydney 2025.

The film stars Tannishtha Chatterjee and JD Chakravarthy, among others.

It is premised on the horrific and cruel witch-hunts of women that continue to take place in India even today.

Rajesh Touchriver’s Dahini: The Witch (2023), which is being screened at the Indian Film Festival of Sydney 2025, opens with the promise of moral urgency. Set in the fictional Bhageerathipura, Odisha, the film dives into one of India’s most horrifying, and least-discussed, social cruelties: the witch-hunts that continue to claim women’s lives in the twenty first century. It’s a story steeped in superstition, misogyny, and systemic neglect, with the potential for blistering commentary on rural violence and gendered oppression. Yet, despite its worthy subject, Dahini fumbles in execution and ends up diluting the very outrage it seeks to stir.

Touchriver, a National Award-winning director, builds his narrative around Kamala (Tannishtha Chatterjee), who becomes the target of a deadly witch-hunt after she spurns the advances of Chuniya (Badrul Islam). With the connivance of a local ojha (Mohd Ashique Hussain), Chuniya plants a human skull in Kamala’s home and spreads rumours that she and her widowed sister, Pallavi, are witches responsible for the village’s misfortunes. The sarpanch’s son is ill, livestock are dying, and the community—gripped by fear and blind faith—descends into mob frenzy. What unfolds is a horrific witch-hunt that culminates in brutal acts of violence, humiliation, and death.

The story itself, based on real incidents of persecution in rural India, should have been enough to sustain the film’s gravity. But Dahini struggles to translate the horror into convincing cinema. Its flaws may not begin with, but hinge vastly, on Ravi Punnam’s dialogues, which are painfully repetitive. Characters circle endlessly around two lines: “Woh daayan hai!” (she is a witch) and “Yeh daayan-vayan kuch nahi hota!” (There are no such things as witches).

Touchriver’s script’s unevenness is compounded by clumsy pacing, a fundamental structural issue, uninspired editing, and dialogue that feels more dubbed than lived. Despite being set in Odisha, most of the film is in Hindi, robbing it of regional authenticity and rhythm. What could have been an unsettling immersion into the psyche of a community gripped by superstition becomes instead a stagey exercise in social messaging.

Even the film’s action choreography falters. Dahini has an abundance of confrontations—villagers chasing women, mobs beating women, physical scuffles. But all the punches look fake, the kicks are limp, and even the most violent sequences lack the raw physicality or theatrical weight they need to jolt the viewer. When Pallavi is dragged out of her home, beaten, humiliated with human waste, and beheaded, the scene almost feels gratuitous.

Actors like Tannishtha Chatterjee and J.D. Chakravarthy (in a largely underwritten role) try to rise above the material. Chatterjee’s Kamala is a woman caught between defiance and terror. But even she can’t salvage the clunky writing. Chuniya, the antagonist, veers dangerously close to caricature, and the film’s portrayal of the villagers lacks nuance.

It’s frustrating because the stakes of Dahini couldn’t be higher. Witch-hunting is not a relic of folklore—it’s an ongoing, gendered epidemic. According to the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), over 2,500 women have been killed on accusations of witchcraft since 2000. The victims are overwhelmingly from Dalit or Backward Castes.

The practice persists, largely because it’s a form of social control over women’s bodies, property, and autonomy. It is this intersection of superstition and patriarchy that Dahini aims to expose—but Touchriver’s treatment never quite transcends the obvious. There’s no psychological excavation, no structural critique of how caste and class determine who becomes the scapegoat. Instead, we get a morality play: evil men, gullible villagers, and a helpless victim.

What makes the film’s shortcomings even more glaring is the contrast between its subject matter and the cultural moment it arrives in. Witchcraft, in recent years, has seen a revival in urban, social-media spaces. On Instagram and TikTok, “witchy” aesthetics—tarot cards, moon rituals, crystals—have become a shorthand for feminine self-empowerment. It’s a reclamation of the witch archetype: the independent, intuitive woman who refuses patriarchal order. But while urban influencers brand witchcraft as liberation, rural women are still being murdered under the same label.

Despite its cinematic clumsiness, Dahini matters. The very act of putting this violence on screen—of demanding visibility for a horror that thrives in silence—is political. In one of the film’s final moments, Kamala screams at her attackers: “If I were truly a witch, you would be running from me, not the other way around!” It’s a line that momentarily cuts through the noise. In that instant, Dahini remembers what it set out to do.

One only wishes the film had done more justice to its own cause. For all its sincerity, Touchriver’s film feels less like an exorcism and more like an unfinished incantation—powerful in intent, but muddled in form.