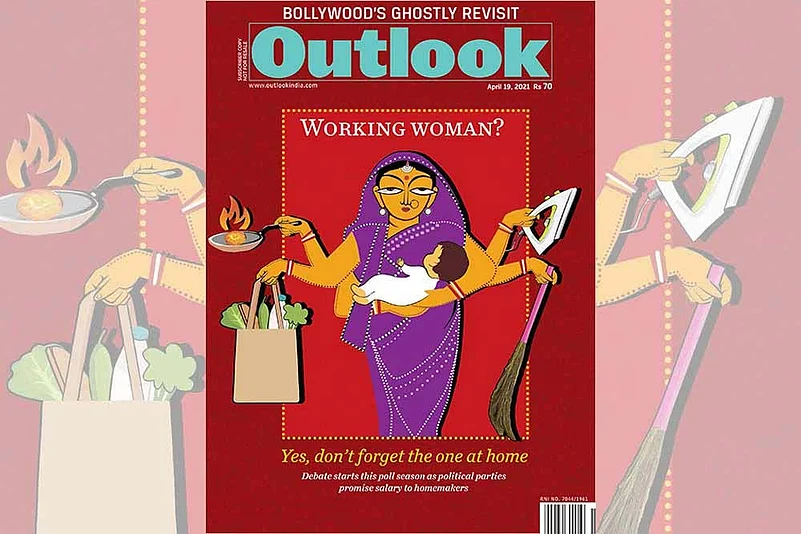

Poll manifestos of several parties—most notably the Congress and Kamal Haasan’s MNM—have promised an unconventional but populist scheme of doling out an allowance, or salary, to homemakers. Questions spring up from this: Should homemakers be paid for their household work and is there a better alternative to make them financially independent. Supreme Court advocate and AIDWA vice president Kirti Singh, former international athlete Ashwini Nachappa, equal rights campaigner Barkha Trehan, and women’s rights activist and Centre for Social Research director Dr Ranjana Kumari weigh in on the topic.

Kirti Singh: What the parties have proposed are welfare measures and they are welcome, but ultimately these are a form of dole for housewives and widows. Unless these are linked with an assessment of what an individual is entitled to—a fair and just entitlement—these wouldn’t be of much help. Also, we have to know the scope of the scheme: how many housewives will it cover; will it be universal; what will be the criteria and the entitlement? The Supreme Court, hearing a motor accident claim, was computing the notional income of a homemaker who had been killed, and made important observations about the economic value of the woman’s work at home and the need to provide compensation in a fair and just manner. The court looked at Time Use in India, a report of the National Statistical Office, which showed the gendered nature of housework, and that women typically spend around seven hours a day doing household work and care work. However, though the court appreciated the time and effort put in by the homemaker, it did not specify how this work should be computed. For instance, it did not say that the homemaker’s work should have the same value as her spouse’s work.

ALSO READ: Who Pays The Homemaker

Ranjana Kumari: While the intention behind the promise of allowance for homemakers is noteworthy, numerous facets still need to be addressed. Firstly, the principle behind compensating women’s unpaid labour is potentially an effective strategy to support their economic empowerment and get rid of inequities in unpaid work. According to the ILO, there is an unfair distribution of unpaid labour globally, with women doing three times more unpaid work than men. Compensating women for their work can provide them with tangible tools for upward socio-economic mobility. However, there is a risk that this strategy could further reinforce the unequal division of domestic labour between men and women. Before monetising work of homemakers, steps need to be taken to not only reduce housework, but also redistribute the work. Domestic and care work should not be the responsibility solely of a woman. Otherwise, the idea of compensation runs the risk of solidifying heteronormative patriarchal principles of man as breadwinner and woman as homemaker. Any policy framework should view domestic work as gender-neutral and provide for any person taking on domestic duties, regardless of gender.

Barkha Trehan: This is a ridiculous idea and must never be implemented. What a housewife does for her family is out of affection and dedication. You cannot put a price to it. Once you start putting a price to it, the entire construct of an Indian family and our values will be threatened. Where will it stop? Will these parties also promise money to children who help with household chores? And what about men who help at home too? Is their effort worthless? Will you also put a price to how many children a wife delivers?

From Left Kirti Singh, Dr Ranjana Kumari, Barkha Trehan, and Ashwini Nachappa.

Ashwini Nachappa: In India, we have always taken care of our parents. It’s been a part of our culture. I would prefer that the government try to ensure the safety of homemakers through other means as doling out sops would lead to a different set of challenges. Every scheme stemming out of appeasement politics has been misused.

How do you determine the notional income of a homemaker?

Kirti Singh: Woman’s income evaluation should be seen as at least equal to the husband’s financial contribution because a woman works long hours at home besides putting in time for her professional commitments if she is also employed. It is impossible to assess the hours put in by a homemaker in comparison to her husband, though the time-use surveys give us some indication, and then say which is of a greater value. The economic worth of a woman’s homework has to be assessed at least at the same level as the husband’s, if not more. When we ask for legal entitlement, we say the homemaker must be considered as equal to the husband and must have an equal right to assets—both movable and immovable. There has to be gender parity. Now, say a woman is educated and qualified for a job, but has become a housewife to cater to her family’s needs at home. You have to consider what she may have been earning in a regular job if she hadn’t been a housewife; the loss of opportunity needs to be considered. Working women, who are also homemakers, have to carry a double burden and the expectation from them is to balance both perfectly.

ALSO READ: Not Content To Be Second Leads

Barkha Trehan: You simply cannot. Who will compute this salary or allowance or pension and on what basis? Different families have different number of members and so the amount of work put in by the homemaker will vary from one household to the other. You can’t have a common sum doled out to every homemaker. Ultimately, you’ll have homemakers fighting over how they are getting less than what a neighbour may be getting.

Ranjana Kumari: Data from the OECD shows that women in India spend 352 minutes per day on domestic work. This unpaid work sustains the economy and contributes 3.1 per cent of the GDP. Is Rs 2,000 (homemaker’s salary promised by the Congress in Assam and Kerala) enough to compensate that? Does it calculate the emotional labour and burden a woman endures? Using time as a value measure through time-use surveys might help produce better labour statistics and policies for women. Making the homemakers’ salary explicitly, and intentionally, gender-neutral will help avoid promoting rigid gender roles.

How will one monitor if the intended beneficiary actually benefits?

Kirti Singh: You have to ensure that the money is credited to an account solely in the name of the intended beneficiary, so she has exclusive access to and control over her money. Simultaneously, you have to run sustained and extensive awareness campaigns. But it is difficult to ensure that the woman has exclusive access to the cash after it has been withdrawn from her account.

Ranjana Kumari: There needs to be a well though-out state policy that ensures the beneficiary is receiving the money. Such policies need to be accompanied with campaigns and awareness workshops that continue tackling issues of gender and power.

Ashwini Nachappa: If we had a proper social security system in place, we would never need these sops. The only way they can make such a scheme work is if they base it on an economic system, giving priority to the economically weaker sections. I don’t know how any government will come up with a formula to make this work. Making a promise is one thing, but implementing it is something else. I don’t know if these parties have done their homework before making such promises in their manifestos. If they have done their research, then they have to make it public so that it can be debated.

Given cases of domestic violence over money, will such cash transfers put homemakers at greater risk?

Kirti Singh: The domestic abuse argument or that the woman may be coerced into withdrawing and handing over the money to the husband or in-laws is a problem because if that’s the environment in a household, then such things will happen irrespective of the woman getting an allowance or not. It happens with working women too. The solution to prevent this from happening cannot be to stop the woman from getting any money. What certainly must be done is to ensure that in terms of immovable marital property, the woman has an equal share in her name because that is more difficult to take away. We have seen this with regard to the property rights that women received following the 2005 amendment to the Hindu Succession Act, which studies have shown made women more financially independent.

Barkha Trehan: Firstly, housewives aren’t the only victims of domestic violence—men suffer too. We just don’t know about the incidents wherein the man is the victim because we have a flawed system and the government doesn’t even keep data of men facing domestic abuse. Even assuming that wives face domestic violence over money, such a scheme would only make matters worse. You’ll have all kinds of cases being filed—most of them false ones—accusing the husband of taking away the wife’s money.

Ranjana Kumari: Simple cash transfers to homemakers could possibly put them at risk of incidents of domestic violence. This is another reason that such a policy needs a thoughtful and gender-sensitive implementation strategy. Without providing safeguards for payments, men may see these payments as household resources. Husbands may believe they have a right to that money, which can lead to power struggles and incidents of violence.

Ashwini Nachappa: Irrespective of whether women are earning or not, we hear of numerous cases of harassment over dowry. This happens even in affluent families. So, what do you think will stop the family members from misusing this money? It is bound to happen. It all boils down to an individual’s intent.

A better way to make homemakers financially independent?

Kirti Singh: There are various possible approaches. If a married couple is buying property, then it would be preferable to have a system of mandatorily making such purchase in joint names of the husband and wife. Government grants of land and other benefits should be given joint names too; if the household is woman-headed or the husband is missing for any reason, they should be in the woman’s name. In agricultural communities, the housewife must be recognised as a equal farm worker and be recognised as someone who can apply for credit from banks and financial institutions. Also, the housewife must have a legally sustainable entitlement to half the share in income and assets of the household. As far as separated or divorced women are concerned, I would suggest a right to matrimonial property act that entitles the woman to half the property and savings of the couple accumulated through the span of their married life, irrespective of whether the woman is employed or is a homemaker.

Ranjana Kumari: The aim should not merely be compensating women’s care work, but also attaching value to it. We need to consolidate housework into a real profession—a long-standing demand of women domestic workers and unions. In Tamil Nadu, domestic workers and their unions have raised legitimate claims to account for the value of housework by thinking about a minimum wage, day-off, protection of basic rights and bodily autonomy.

We need to think about how women can be encouraged to live to their fullest potential and participate in other spheres of life, economic and political, without being chained to their homes. The government needs to continue investing in initiatives that reduce housework. The government can also invest in regular time-use and labour-force surveys to capture the work that homemakers do.

The government must also continue investing in primary drivers of empowerment such as women’s education and political participation. Initiating more solutions that provide security to women like focusing on women’s right to property, resources for battered women, closing the gender gap in higher education institutionsand so on are also foundational to better economic outcomes for women.

Ashwini Nachappa: What’s important is that every citizen of this country lives with dignity and merely doling out money will not ensure that. However, many things can be done. For instance, governments can provide free medical care to all homemakers. They can also build good quality old-age homes, which are like a community by themselves. This is important, because with every person entering the workforce these days (men and women alike), not many people have the time to take care of their ailing, old mothers. In such a case, they should have the option to move out of their child’s home and live a life of dignity. Also, whichever member of the family earns, be it the husband or the children, they should give a part of their income to the homemaker. They should make sure a small amount from their income goes to the piggy bank of the mother/wife for her personal use.

—Debate curated by Outlook Bureau