Summary of this article

1.Twenty years on, India’s Gender Budget has helped mainstream gender tracking in public spending, yet there is a long way to go for ensuring increased women’s labour force participation.

Experts flag weak focus on care work, labour force inclusion, safety infrastructure, and underfunding of schemes like Nirbhaya.

Feminist economists, stakeholders demand a more inclusive, bottom-up gender budgeting process that prioritises work, care infrastructure, and informal women workers

In India, the Gender Budget is a policy tool used to analyse and track government spending from a gender perspective, to ensure that women and girls benefit fairly from public expenditure. Introduced in 2005–06, it does not mean a separate budget for women, but a detailed statement in the Union Budget that lists schemes where 100% or at least 30% of funds are meant for women.

The Gender Budget helps assess how allocations for sectors such as health, education, livelihoods, nutrition, housing, and social protection address structural gender inequalities, including unpaid care work, low workforce participation, and limited access to resources. By making gender impacts visible in fiscal policy, it acts as an accountability mechanism, pushing ministries and states to design and implement programmes that promote women’s empowerment, safety, and economic independence, rather than treating women as passive beneficiaries.

While its impact has varied due to uneven implementation and limited outcome tracking, the Gender Budget remains a crucial intervention that has reframed budget-making in India by recognising that public spending is never gender-neutral and must actively address the deep-rooted social and economic inequalities faced by women.

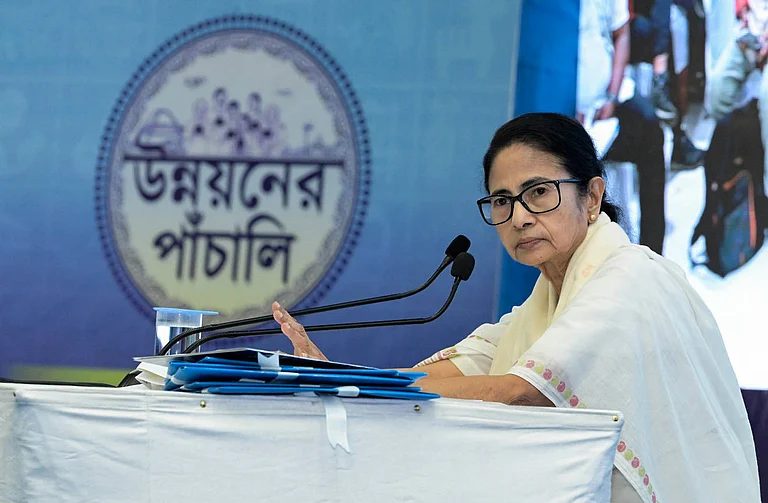

“From the beginning of the gender budget in India 20 years ago till now, we have been fairly successful in mainstreaming the gender budget as a tool to track financing for women’s empowerment. However, there is much emphasis on social protection schemes for women in the gender budget, such as PM Awas Yojana, etc. Though this is crucial, the schemes and funds that contribute to women’s labour force participation—their economic growth—remain lower in the gender budget,” says Mitali Nikore, founder of Nikore Associates, an economic research think tank. Nikore has also worked with the Ministry of Women and Child Development on several projects and consultations.

Throwing light on the nuances of the gender budget and its vision to achieve gender equity, Nikore adds, “India needs to look at programmes and schemes in artificial intelligence, technology, and research from women’s participation and growth perspectives. Funds and infrastructure for women’s participation in the labour market should be given more importance. Providing more working women’s hostels in tier-two and tier-three cities, crèches, safe transport, safe workplaces, and funds for lower- and middle-income entrepreneurs should be prioritised along with social protection schemes.”

Nikore also notes that earlier only four to five ministries would engage with the gender budget process. Over the years, the number of ministries and line departments engaging with the gender budget has significantly increased, which is a key success of the idea.

History of the Gender Budget in India

In India’s Gender Budget Statement, Part A covers schemes with 100% allocation for women, such as maternity benefits or women-only welfare programmes. Part B includes schemes where at least 30% of the funds are meant for women, even though they are not exclusively for them, such as education, health, or livelihood schemes. Part C (introduced later) captures women’s employment-related provisions, mainly government spending on women employees, including salaries and benefits, to reflect the state’s role as an employer in promoting gender equity.

India’s Gender Budget emerged from sustained feminist advocacy and global commitments to gender-responsive budgeting, particularly after the 1995 Beijing Platform for Action, which urged governments to integrate gender concerns into public finance.

The idea gained ground in the early 2000s through the work of women’s movements, economists, and institutions such as the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP). This led to the formal introduction of the Gender Budget Statement in the Union Budget 2005–06, making India one of the first countries in Asia to institutionalise gender budgeting.

Over time, the framework expanded from a symbolic listing of women-oriented schemes to a more structured fiscal tool covering multiple ministries, with guidelines issued by the Ministry of Finance and capacity-building initiatives at the central and state levels.

Limitations and Challenges of the Gender Budget

A limitation of the gender budget is the lack of focus on care work—particularly schemes and policies that address paid care work. The recent Economic Survey 2025–26 illustrates that women in India still shoulder a disproportionate share of unpaid household and care work, spending significantly more time on these tasks than men, which limits their access to paid work and economic opportunities. It observes that care responsibilities often conflict with formal employment, highlighting the need for stronger care infrastructure, more equitable sharing of domestic work, and flexible work policies to enable women to enter and remain in the workforce.

The Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA), a non-profit based in Delhi, was invited by Union Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman to make submissions on behalf of poor women in the informal sector during pre-Budget consultations in November 2025 for the Union Budget 2026–27.

SEWA made key recommendations focusing on increasing the productivity of women workers through enhanced social protection and better employment opportunities for young workers in this sector.

These submissions included reinstating and allocating funds from Central Budget support for Beedi Worker Welfare (health, scholarships, ID formalisation) after the repeal of the Beedi Welfare Cess; using unspent BOCW Cess (Building and Other Construction Workers’ Cess) to link registered construction workers with ESIC and cover employer and employee contributions for comprehensive healthcare; expanding climate protection for informal workers by scaling sector-specific climate insurance; waiving 18% GST on such products; creating a blended-finance “Climate Fund” for adaptation, mitigation, and insurance access; and strengthening NAMASTE (the national scheme for waste pickers) with hybrid (digital and physical) registration, enhanced scholarships for waste-picker children, and reforms in solid waste management rules to reserve key work (door-to-door collection and MRFs) for registered waste pickers and cooperatives.

Whether these demands find reflection in the Gender Budget 2026–27 will become clear after the Union Budget is presented on February 1.

Feminist economists have also observed that the schemes and allocation of funds listed in the gender budget for women’s empowerment are highly demand-driven. For instance, if there is greater demand from line departments in public health focused on women’s health and nutrition, these receive priority in the gender budget. On the other hand, schemes that enable women’s participation in the workforce are given less importance in comparison.

State-level cash transfer schemes, which provide women with amounts ranging from Rs 12,000 to Rs 36,000 annually (varying from state to state), do help women, but they do not contribute to sustained labour force participation.

Allocation for women’s safety is a crucial component of the gender budget, yet the Nirbhaya Fund for women’s safety has drastically reduced over the past 10 years. Feminist researchers argue that the limited funds are also being used for cosmetic changes—for example, installing CCTV cameras and purchasing police patrolling vans. Meanwhile, initiatives such as one-stop centres, created for first-line response and redressal in cases of gender-based violence, are floundering. However, this is not due to limitations of the programme itself, but rather a failing systemic approach to funding.

Gender Budget Consultations Need Inclusion and Diversity

The gender budget consultation process involves discussions between the Ministry of Women and Child Development, line ministries, and states to identify programmes that benefit women. These consultations help assess allocations, refine priorities, and ensure gender concerns are reflected in budget proposals before finalisation. However, the consultation process needs to be more inclusive and adopt a bottom-up approach by inviting diverse stakeholders, including women working on the ground.

“There is huge scope to ensure inclusion, diversity, and an intersectional approach among stakeholders invited for pre-budget consultations. There should also be dialogue on how many SC, ST, OBC, and Muslim women are given opportunities in such consultations,” said a feminist activist who was invited for the pre-budget consultation for the Union Budget 2026–27 and wished to remain unnamed.