Summary of this article

The density and intensity of life, faith, worship, poetry, music, food, and politics in Banaras lie in the mesh of people and places populating the city

In some sense Banaras has become unrecognisable for all, ever since Narendra Modi adopted it as his electoral constituency in 2014

Symbols of this political imprint include the NaMo Ghat, named after the Prime Minister’s initials, built at a far end of the river, away from Assi Ghat.

It’s been almost six years since my mother’s death. I am travelling with the American scholar, Linda Hess, an expert on Kabir, the medieval saint poet of Banaras, predecessor of Tulsidas by about a century. Linda, who is already 80 years old, has been coming to Banaras since she was a student. She is the star speaker at a music festival called “Kabira”, after her poet. Since I am her companion I get to stay with her at Ganges View, the storied hotel on Assi Ghat. We chat with the proprietor, addressed as Shashank Bhaiyya by everyone, who comes from a family that migrated from Bihar some generations ago and now owns most of Assi Ghat. The hotel has a beautiful collection of books and art, and is a hub for scholars and writers from across the world who stay there when they visit Banaras.

The Alice Boner Institute and Harmony Bookstore next door to the Ganges View make for an attractive little cluster of institutions. Just a bit further up, in Lanka, is the sprawling campus of the Banaras Hindu University, established in 1916 by the nationalist leader, Madan Mohan Malaviya. We run into a well-known professor visiting from an American university on the terrace one morning, and Linda recognises him. He says not to mention on social media that he is in Banaras, as one group of his Indian friends and colleagues will be offended to learn that he is present in their city without their knowledge. He’s trying to complete a manuscript in the balmy Banarsi winter.

Linda has spent half a century working on the two greatest Banarsi poets of medieval India—Kabir and Tulsidas. Her familiarity with the city is intertwined with her scholarly interests and human relationships built over a long time. That she is American, born Jewish, a practicing Buddhist, a woman, an academic who has spent her career at Berkeley and Stanford—somehow all these facets of her identity have become seamlessly enmeshed with her dedication to Kabir and her love of Banaras. It is as if the poet speaks directly to her, across the centuries. In pursuit of his words and voice she has become closely connected to the musical traditions that preserve and propagate Kabir’s poetry in song. Thus the classical Hindustani maestro, Kumar Gandharva (1924-92) and the folk singer, Prahlad Tipaniya (b. 1954) have been a part of her passionate journey with Kabir’s legacy.

Seeing Banaras through Linda’s eyes is to see it as unrecognisable relative to the 1960s, ’70s and ’80s, when she spent time there as a young researcher and a seeker of sorts. But it is also to see the city from the inside—from the ghats looking at the river, rather than how I see it, from a boat gliding past the panorama of the ghats. The density and intensity of life, faith, worship, poetry, music, food, and politics in Banaras lie in the mesh of people and places populating the city, not in the eyes of visitors like me who see it from a distance, laid out like a set on a stage, picturesque, inviting and mysterious. But there’s a long history of the city being seen from afar, observed from the water, painted and etched and sketched and photographed from colonial times, the very acme of the Orientalist gaze, half-imagined and half-dreamed, as insubstantial for the onlookers as it was real for the inhabitants.

And in some sense Banaras has become unrecognisable for all, ever since Narendra Modi adopted it as his electoral constituency in 2014 when his party, the BJP, was elected to power and he became India’s prime minister. The city, known by its formal name, Varanasi, is literally not even Banaras when seen in its avatar as Modi’s seat in Parliament. Typically (for him), he has built a ghat at a far end of the river from Assi called NaMo Ghat, after his own initials.

But his real intervention, perceived as decisive in changing the city’s historical geography, is the redevelopment of what is now called the Kashi Vishwanath Corridor, the entire area of lanes, houses, ghats and shops around the Vishwanath temple complex, and the Gyanvapi mosque that abuts its boundary wall. Together with the building of a new Parliament House in Delhi and a new Ram Temple in Ayodhya, the Kashi Vishwanath makeover has the imprimatur of the Modi government’s authoritarian ambitions.

The music festival at which Linda is speaking arranges a tour of the Kashi Vishwanath Corridor for delegates. As expected, the place looks nothing like it used to. Instead of the cramped alleyways with their tiny shops, eateries and shrines all higgledy-piggledy pressing around the temple and mosque, there are massive pyramidal steps going up from the river to a monumental triple-arched gateway, and inside it, a huge plaza, more gateways, connected courtyards, eventually leading to the sanctum sanctorum. The food court, the security arrangements, the wide open spaces without ornamentation or shelter that have to be traversed barefoot, the absence of greenery and water, the forbidding stone facades of various boundary walls, all bespeak fascist hubris rather than human scale.

Manikarnika, the burning ghat adjacent, is walled off. The Gyanvapi mosque is hidden behind scaffolding; it no longer functions as an active place for prayer, and no doubt it will be demolished sooner or later. The god at the heart of this enormous structure seems small and inconsequential, no longer Vishwa-Nath, ‘Master of the Universe’, whose power has sustained Kashi for centuries but a mere idol, dwarfed by the gigantic architectural apparatus put in place by the Hindu nationalist state to further its own ends. These include spending money freely towards ‘developing’ the prime minister’s constituency, ‘cleaning’ and ‘beautifying’ the riverfront to encourage religious tourism, eliminating all traces of Muslim history from Banaras, and most importantly, asserting the demographic, cultural and political dominance of the majority community.

Linda didn’t want to see what had happened to Kashi Vishwanath, and it wasn’t just my visit to Kashi Vishwanath that bothered me. All of Banaras seemed changed—and not so subtly, either. On Assi Ghat, early morning Hindustani classical music concerts or free yoga lessons—all amplified by loudspeakers. On Dashashwamedh Ghat, a nightly performance called Ganga Arti, a totally ersatz ritual branded as ‘timeless’ (it was invented as recently as 1998, it seems). And the Kashi Vishwanath esplanade, with special lights and high security surveillance cameras, regimenting and disciplining a city traditionally considered recalcitrant to the whims of political power. The ghats seemed somewhat cleaner but the river looked as murky as ever. The little eatery near our hotel, once a private home where Linda had rented a flat long ago, now served freshly-made thin-crust pizza and chilled smoothies.

Linda was roiled by her memories, and I by mine. We made for a couple of fairly neurotic roommates. But she was doing worse than I was—she had a sore throat, jet-lag, and was thirty years older than me. Her real grief, though, was connected to the war in Gaza that had started just a couple of months before we got to Banaras, one that she opposed fiercely. She was constantly upset by the mounting civilian casualties, the dead babies and maimed children, and the Israeli army’s increasingly ruthless attacks on defenceless Palestinians. She scoured the Internet for news from America and Israel. Somehow, when the day came, she managed to wear a beautiful silk sari and deliver an absolutely riveting account of her life with Kabir at the festival. To see her on stage she seemed like the young woman and free spirit she must have been when she first started visiting India.

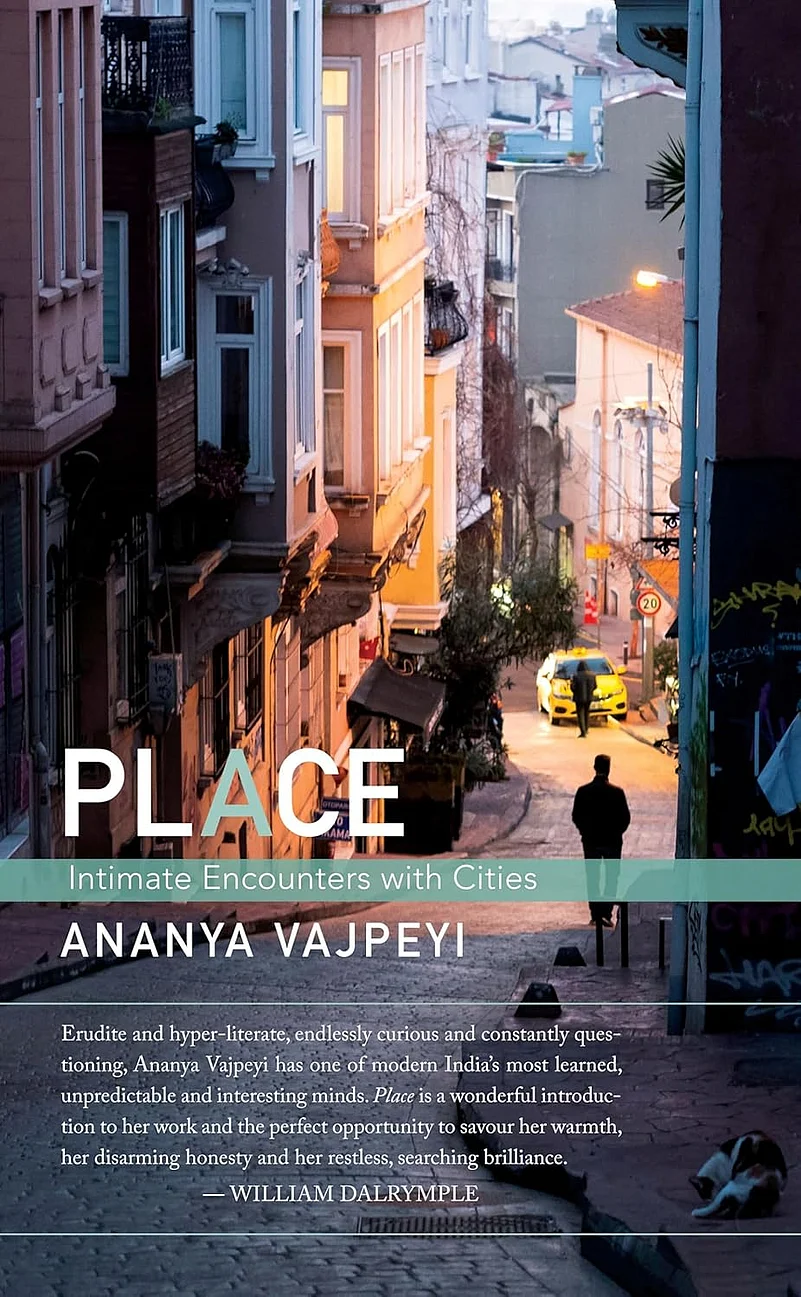

(Excerpted from Place: intimate encounters with cities by Ananya Vajpeyi, published by Women Unlimited Ink)