Keshav Kunj, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh’s (RSS) rebuilt headquarters in Delhi, is a compact city.

Keshav Kunj broadcasts the RSS’ determination to establish an urban anchor in the capital.

The building is in active use, with senior leaders relocating their offices and national meetings are already underway.

On February 19, 2025, in New Delhi, media and members of India’s Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh’s (RSS) gathered around three towers that stood tall in Jhandewalan. These were not temples, nor shiny corporate campuses, but the RSS’ nerve centre—a new campus for an organisation that has itself seen a resurgence and rejuvenation over the past century.

Keshav Kunj, the RSS’ rebuilt Delhi headquarters, is a compact complex: three towers named Sadhana, Prerna, and Archana, comprising approximately 300 rooms, three large auditoriums, a library loft on the 10th floor, a five-bed hospital, manicured lawns, and a Hanuman shrine within.

“The Sangh’s headquarters will always be in Nagpur; that is where we started. But, Delhi is India’s capital city and must be accorded that importance,” says Narender Thakur, the Akhil Bhartiya Sah Prachar Pramukh.

Keshav Kunj spans about five lakh square feet spread across four acres and cost Rs 150 crore, which was raised, reportedly, through public donations through over 75,000 contributors.

For the Sangh, which is celebrating its centenary this year―having been founded in 1925―Keshav Kunj is the embodiment of its dual-ended plan for the future of increasing the public’s sense of civic duty through volunteering and of increasing its own presence in India and globally.

The refurbished Keshav Kunj offers the Sangh a greater capacity for training the youth and for hosting larger events. However, these huge towers also symbolise the RSS’ fixation for establishing a powerful presence in the capital. The building is in active use, with senior leaders relocating their offices and national meetings are already underway.

Past the gates, modesty meets grandeur. The Ashok Singhal auditorium features seating for large crowds. One tower houses the Sangh offices, a medical dispensary, a hospital floor that is used for physiotherapy by its members and citizens who live around the building, says Thakur. The other two towers are residential.

The Keshav Pustakalaya library has “over 10,000” books, says Ankit, a 31-year-old who started working in the building as a librarian earlier this year. “Many people come here to do research—we have religious books from every religion, we have history books and also books on the history of the RSS, so often, people who are doing their PHD or higher studies on the Sangh come here to do their research,” he adds.

There is a mess hall and a canteen, and parking for 135 cars.

Rajasthani and Gujarati architectural motifs, combined with granite frames that reduce timber use, blend tradition with sustainability.

The variety of facilities available at Keshav Kunj speaks to the Sangh’s view of itself. This is not just an organisation building, but also a stage for its long-term influence at the national level. Spaces like the library and research rooms show long-term ambitions of training members, supporting research, increasing influence among citizens, both young and old, through sewa, and coordinating a national network of workers and volunteers.

Keshav Kunj’s funding remains a striking point. Sangh functionaries had earlier told the media that 75,000-odd donors contributed sums ranging from Rs 5 to several lakhs of rupees. “The Sangh does not take money from anyone outside—we fund ourselves through individual donations, and no institutional donor money―not even the government’s―is taken,” says Thakur.

Opposition politicians label the building a symbol of ostentation, while Thakur says it a resource hub in line with Delhi’s political significance as India’s capital city. These competing narratives say a lot about Keshav Kunj’s importance. It is both: for the RSS, it’s an operational centre and for the Opposition, it’s a public signal about the Sangh’s possible role in India’s future.

A 100-year-old Repertoire: Service, Training, Influence

To see what Keshav Kunj may mean for the next decade or two, let’s consider what the Sangh already does and the opportunities for scaling. The RSS relies on a familiar set of activities: daily shakhas for training, social-service relief, educational outreach, and a broad network of affiliates across politics, academia, and the media. The new headquarters enables greater centralisation and professionalisation for these initiatives. It now serves as a training hub, research library, accommodation for scholars, and a venue to build wider networks.

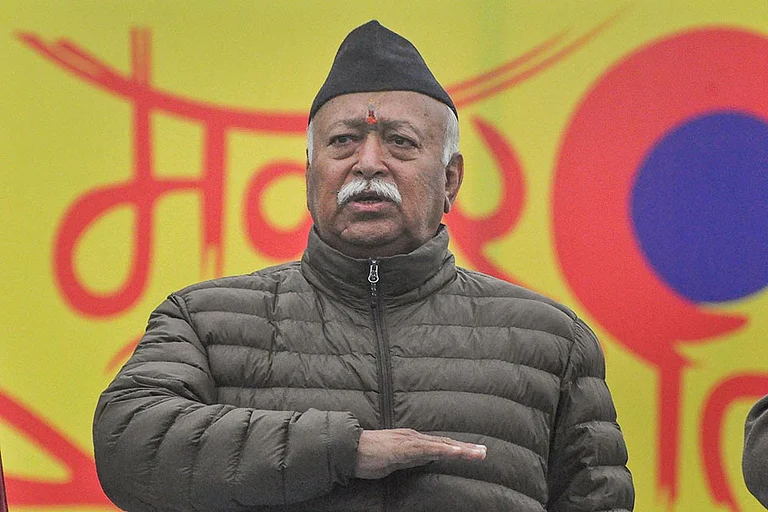

In recent speeches, RSS Chief Mohan Bhagwat called for not just cultural regeneration, but national self-reliance and enduring social mobilisation. At Keshav Kunj gatherings, Bhagwat asked workers to match the building’s impressiveness in their work and pursue larger goals: national resurgence, cultural confidence, and disciplined service. For an organisation that values institution-building over individual recognition, the new headquarters supports steady, long-term mobilisation.

Keshav Kunj, with its training, research, events, and accommodation, suggests three possible paths.

First, consolidating urban presence. The Sangh’s strength lies in its rural and small-town networks. A modern capital hub signals a shift towards urban engagement, recruiting youth for city shakhas, building ties with urban NGOs, and hosting cultural programmes to integrate itself into cosmopolitan life―Karyakarta Milan and other events model this expansion.

Second, knowledge production and narrative control. A dedicated library and research suites enable the Sangh to host or fund scholars and researchers, while affiliated publications help reinforce favoured ideas. In time, this may yield more organised research, curated exhibits, and policy recommendations influenced by the Sangh.

Third, institutional resilience and state interfacing. Through social, cultural, and affiliate networks, the Sangh engages with state institutions. A large, modern Delhi hub lets it host delegations, convene experts, and partner in civic events and relief work. A refurbished Keshav Kunj enables more engagement in education reform, disaster response, and health, in an attempt to turn legitimacy into a durable policy and public influence.

A Capital Stage For Contestation

Keshav Kunj is both a centre and a stage. It will be used for internal rehearsals, including training, meetings, and planning, as well as public performances where politicians, scholars, and influencers come together under the Sangh’s roof. That mixture is what makes the building consequential. Keshav Kunj will not determine the Sangh’s future on its own, but it will give the organisation a steady, visible base to test and normalise its practices in the national capital. For the Sangh, the prize is legitimacy, more than being legally recognised. This involves shaping the public’s daily habits in the capital: the language of civic duty, the rhythm of community service, and the architecture of meetings and debate. For critics, the prize is different: the conversion of cultural muscle into institutional power.

If institutional architecture reveals anything about intent, Keshav Kunj suggests that the Sangh plans are for the long term. It is an investment in time: rooms that will host people, auditoriums that will hold arguments, and a library that will accumulate texts.

For a capital that is always staging the interplay of ideas and power, the opening of the RSS’ new Jhandewalan address is now another scene to watch. The Sangh will press its case from inside the towers named Sadhana, Prerna and Archana―that it can be modern and rooted, disciplined as well as grand. Others will watch to see whether that modernity deepens plural participation in civic life or narrows the public debate to one script. Either way, Keshav Kunj has made a long-term argument in architecture, which New Delhi must now answer.