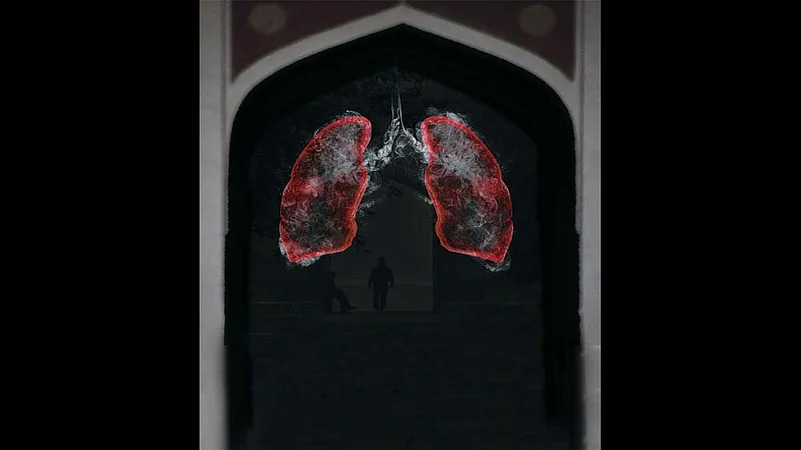

The clock is ticking for Delhi. It’s time, once again, for the haze and smog to tightly wrap the city after the monsoon cleansed the air considerably. The first, ominous signs appeared by end-September. Delhi’s air quality index (AQI) shifted from ‘moderate’ to ‘unhealthy’ even for a relatively clear blue sky. According to AQI data, the capital had only eight ‘satisfactory’ days this September. By mid-October, air quality moved to ‘hazardous’; the state government enforced the graded response action Plan (GRAP), banning diesel generators. Anu Mukarji of Gurgaon, mother of a teenage boy, dreads the annual smokescreen. As the pollution metre cranks up with a nip in the air, respiratory problems resurface. “As a parent I feel helpless locking my son indoors. There is a dilemma of choosing between two devils—indoor and outdoor air. Every year we see a repeat,” she says despairingly. The foul air triggers breathlessness, wheezing, coughing, and Mukarji had to rush her son to hospital emergency in the middle of the night once.

Air pollution has bedevilled many, forcing them to take drastic steps. Take Anuja Bali Karthikeyan, who shifted from Gurgaon to Pune when her seven-month-old son developed respiratory illness. Parents dread the Delhi winter—as air gets poisonous, children, a vulnerable group, develop breathing issues. “Evidence suggests that COVID-19 has a sinister link with air pollution. A higher AQI is likely to increase risk of infection and mortality. Post lockdown, we must avoid the temptation, in the name of economic recovery, to go back to intensive use of fossil fuels, unrestrained use of automobiles or inaction to stubble burning,” says D.J. Christopher, professor of pulmonary medicine at CMC, Vellore.This year, stubble burning showed up in September, much earlier than usual, at the Punjab Remote Sensing Centre. “If alternative arrangements are not made, pollutants like particulate matters and toxic gases like carbon monoxide and methane will cause severe respiratory problems, which will worsen the COVID-19 situation as the virus also impacts the respiratory tract,” a news report quotes Sanjeev Nagpal, advisor to the Union and Punjab governments on crop residue management.

ALSO READ: Chokehold

“Last year, nearly 50,000 cases of stubble burning were reported in Punjab. It contributes about 18 to 40 per cent of atmospheric particulate matter in the northern plains. It also emits toxic pollutants like methane, carbon monoxide and carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons,” said Nagpal. Last year’s stubble burning in Punjab and Haryana had contributed to 44 per cent of the pollution in Delhi-NCR, according to System of Air Quality and Weather Forecasting and Research (SAFAR), the Ministry of Earth Science. Vehicular emissions contribute between 25-30 per cent.

According to chief minister Arvind Kejriwal, anti-pollution measures by neighbouring states are failing to clear Delhi’s air. An emergency meeting was held on October 1. Five states—Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, Haryana, Rajasthan and Punjab—participated; the Centre allotted Rs 1,700 crore for stubble management. Currently, 80 per cent subsidy is being given to cooperatives and 50 per cent to individuals on machines to clear stubble. The Delhi government has been directed to take action on 13 city hotspots. Fifty teams of Central Pollution Control Board officials will be deployed to take action.

ALSO READ: Warrior Moms, Crusader Kids

Amongst possible solutions discussed at the meeting was the microbial decomposer capsule, a chemical that can decompose stubble. Delhi will start sprinkling the solution from mid-October over 800 hectares; Uttar Pradesh will do the same for 10,000 hectares.

A Capital Battle

Delhi’s chronic foul air is India’s oldest running pollution battle. Around 1998 to 2003, as Delhi gasped for fresh air, Supreme Court directives and public campaign catalysed initial measures. These included the shift of the capital’s public transport from diesel to CNG, shifting of polluting industries and removal of15-year-old commercial vehicles. They helped stabilise pollution levels and bought some time.

ALSO READ: Startup Army Is Airborne

That time ran out by 2007-08—air pollution started to spike again, with an exponential rise in numbers of private diesel vehicles and construction activities. By 2014, thick winter smog choked the public, as Delhi kept on adding vehicles. That year, it added around 1,400 private vehicles daily. The last economic survey put the total number of motor vehicles in Delhi NCR at 109.86 lakh on March 31, 2018.

“Between 2010 and 2014, we saw more awareness and public conversation on air pollution and smog. The dieselisation of cars hogged attention despite a strong industry pushback,” says Anumita Roychowdhury, executive director, Centre for Science and Environment. Since 2015, judicial interventions, science-based evidence in courts and public action sped change towards multi-sector clean air plans in Delhi-NCR, adds Roychowdhury.

ALSO READ: ‘Our Clean Air Plan Is A Shot In The Dark’

However, anti-pollution measures that followed were difficult to implement and were contested in the SC. Nonetheless, all coal-based power plants closed down, most legal industrial units moved to natural gas, and there was a virtual ban on all dirty fuels, including coal, pet coke and furnace oil in all sectors in Delhi. Daily entry of trucks declined drastically due to an environment compensation charge, restriction on old trucks and diversion through peripheral expressways. A fleet renewal based on BS-IV emissions standards took place during the decade, as share of diesel cars dropped due to a ban on 10-year-old diesel vehicles and environment pollution charges on big diesel cars and SUVs. In recent years, BS-VI fuel and vehicles have been introduced; nearly all commercial vehicles run on CNG and Metro ridership has increased.

“After these difficult measures, Delhi bent the annual pollution curve, as evident in air quality data. But the big lesson is that even after this reduction Delhi needs to reduce its PM2.5 levels by another 67 per cent to meet the national ambient air quality standards. Just imagine, how more difficult measures are needed for the next big cut!,” says Roychowdhury. Delhi has the highest number of real-time monitoring stations at 38, whereas both Mumbai and Bangalore come second with 10 each.

ALSO READ: Throwing Straws Against The Wind

Gaps In Action

Overall, India’s manual monitoring stations far outnumber real-time data stations. The crux of the problem, according to Chandra Bhushan, CEO, iFOREST, lies in the status of air pollution monitoring—tracking, collating, analysing various data sets. “The government is cherry-picking data to suit its narrative. Continuous monitoring of air pollutants began in 2018 in Delhi while CPCB data between 2012 and 2018 shows that the amount of PM2.5 has doubled during this period—from 63 ug/m3 to 121. Air pollution levels have only increased in Delhi, not reduced, as claimed by government advertisements,” says Bhushan.

More than 1.16 lakh children died in India in 2019 due to indoor air pollution—the main culprit being smoke from kitchen chulhas .

There is lack of consensus, too, on the status of monitoring and baseline data. “Air pollution is a multi-sectoral problem involving multiple institutions and we have huge capacity and infrastructure deficits. We urgently need a national-level emission inventory—emission factors, data transparency and sources in open domain to understand and plan better,” says Tanushree Ganguly of the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW).

According to Roychowdhury, areas where action has been slowest in Delhi include little progress in citywide public transport, walking and cycling strategies and measures to control vehicle numbers. The auto industry lobby delays targets for electric mobility too. Also lagging behind are plans to control pollution from small/medium scale industrial units, including informal recycling units, industrial waste burning and dust management. For example, there are around 3,000 brick kiln units in Delhi-NCR. Large consumers of coal, they are highly polluting.

Solid waste, construction and demolition waste, plastic waste and e-waste pose another problem. There is enormous infrastructure deficit for decentralised segregation, recycle and reuse of waste. Delhi needs a new set of measures to bridge the gap between policy and implementation. Symbolic solutions like smog towers will never work.

ALSO READ: How To Not Waste A Crisis

In a research paper—Can We Vacuum Our Air Pollution Problem Using Smog Towers?—Sarath Guttikunda and Puja Jawahar of Urban Emissions, a repository of information, research and analysis related to air pollution, debunked the plan to vacuum away outdoor air pollution, calling it unscientific. Since air has no boundaries, to assume that one can trap, clean and release air into the atmosphere is a risible idea.

As per CEEW estimates, if the smog tower at Lajpat Nagar makes a difference in air quality, Delhi would need at least 2.5 million towers at a cost of Rs 1.75 lakh crore. For a fraction of that cost, says Guttikunda, Delhi can increase its urban bus fleet to 15,000, create infrastructure for walking and cycling, and improve waste collection and landfill management.

ALSO READ: The Trash We Inhale

But such arguments haven’t reached ears in high places. Earlier this month, Kejriwal grandly announced: “To curb pollution, Delhi government has decided to set-up a Rs 20-crore smog tower in Connaught Place, in addition to the…tower coming up in Anand Vihar. This tower will suck the air from the top & release filtered air near the ground.”

Trees, not medieval-sounding smog towers, are a much better option: species like Banyan (Ficus Benghalensis), Peepal (Ficus Religiosa), Jamun (Syzygiumcumini), Champak (Magnolia champaca) and others are known to filter particulate matter and act as natural air filters. Ironically, and criminally, should we say, Delhi has chopped 15,000 trees in the last three years for ‘developmental’ activities. Its two ecologically rich zones—the Aravallis and floodplains of the Yamuna—continue to be misused.

During the COVID-19 lockdown, air pollution trends showed a remarkable improvement across the country. Ambient air pollution levels improved as much as 50 per cent. Even the crop residue burning during April, after harvesting of the Rabi crop, went largely unnoticed. The cleanest day in Delhi was also recorded during a lockdown day—on May 30, when heavy rains washed down the city to a 24 µg/m3 24-hour average. Otherwise, the cleanest day without a major rain event stood at 26 µg/m3 registered on March 28. But to sustain such pristine standards, tougher norms and better planning with a generous assistance of science seems to be the only way forward.