Intangible, fluid and a lived experience of communities, folk music is a heritage that has had to fit in the compelling, reductive moulds of the mainstream music industry and governmental networks. In conversation with Arshia Dhar, renowned Hindustani classical vocalist Shubha Mudgal explores the perceptions around this complex aural territory and their implications. Excerpts:

In music, we’ve been seeing something of a folk revival of late. But, in a subcontinent blessed with such aural richness, how did we come to a stage where we would need a revival at all?

I am afraid I cannot agree with the premise that there has been a recent revival of folk music. While folk music is by no means extinct in India, it continues to swim in troubled waters. One of the many problems folk music currently faces is that a large part of the repertoire is at risk of being lost forever because exponents find acceptance only for catchy tunes that can be danced to. Therefore, even among the more successful of folk artistes, for example the popular Langa and Manganiyar artistes of Rajasthan, there is a growing concern that their once large and diverse repertoire is shrinking rapidly. A large part of folk music is linked to life cycle rituals and work activities and may therefore never find acceptance in proscenia presentations. For example, laments sung only as part of death rituals may never make acceptable concert repertoire. Current exponents of these forms may end up never learning them from their elders.

But to get back to your question, it comes as no surprise or shock to me that we are discussing the need to revive folk music. For decades, support for folk arts came from State-funded organisations set up in the Nehruvian era, such as the Sangeet Natak Akademi (SNA), or from private trusts and individuals with a keen interest in conserving the arts. In recent times, the Jaipur Virasat Foundation and its Rajasthan Rural Arts Program as well as the Mehrangarh Museum Trust have been working on providing sustainable livelihood programs for folk artistes in Rajasthan. However, with State-funded organisations like the SNA, there has been little or no attempt to review strategies. Maybe, we need to accept that State funding of this nature is now irrelevant and work towards re-building institutions with realistic goals.

What of representation in other mediums of broadcast, which have multiplied considerably?

With over 3,000 traditional and online radio channels operational in India, the broadcasting boom has also ignored the folk arts to a large extent.

Further, folk music often found its loyal audience in regional communities. Today, exponents of folk music aspire to move to cities for better opportunities, where the standards of success and popularity are set by Bollywood. As a result, urban audiences accept folk music only if it is packaged in the Bollywood mould. What message are we giving then? That if you present a beautiful folk song with traditional instruments, you are orthodox and not moving with the times, but if the same song is presented with an urban band, you are “contemporary” and can even claim to be a modern day saviour of folk music. As an artiste, I feel musicians must have the freedom to present their work as they wish to. And, as a student of music, I feel I would like to hear and learn from both the conventional and new formats of presentation.

Popular Indian cinema is famously a ‘musical’ genre, and folk’s near-eclipse has to do with how it saturated the whole space. Did it create a new aesthetic that was too ‘smooth’ and ‘thin’?

I would not lay the blame solely on Bollywood. It has mass appeal that currently extends beyond India to other parts of the world and it comes from its ability to do aggressive marketing. But blaming Bollywood for the eclipse of folk music is as unfair and unreasonable as a recent malicious article in a publication that blamed the eclipse of musicians on the many concert opportunities that a popular young star of Hindustani classical music is able to secure through what is perceived as her marketing talent and not musical merit. If a singer gets a large number of concert opportunities, what is he/she supposed to say to organisers who approach them with more invitations? No no, please call other artistes and not me, because I have too many concert opportunities?

Bollywood has the money and mass appeal to buy media space in every format available to us today. And the media too must accept some part of the blame. When was the last time you read or saw a cover or lead story on a folk artiste? We are all to blame as a society, which is insensitive to its many art forms.

Film music often filters the ‘coarse’ sound of folk for the public, all the while cannibalising on it for melody and other musical resources.

In recent times, some of the biggest hits in Indian film music have been the raunchy, item numbers that borrow dialect, rhythm and often entire compositions from folk music. No one has had a problem accepting them. On the contrary, people, young, old, children, all take great delight in these numbers with little thought for context and content.

The ‘Golden Age’ of film music also coincided with the dawn of the new Republic. Singers like Lata Mangeshkar and Mohammed Rafi have been called the ‘voices of the Five-Year Plan’. Would you agree that part of their popularity stems from how they embodied the new ideals…Lata as a kind of pure, virginal femininity and Rafi as the ‘new man’, both cleansed of the old ‘impurities’? The sexually aware, melancholic, mature voice of thumri, for instance?

I would say that their popularity truly rests on their indisputable mastery over their art and their ability to become the singing/playback voices of an absolutely amazing range of on-screen characters. Lata ji has been the playback voice of actors of all ages from child actors to young heroines to dowager matrons. The expressive range is also enormous and so convincing that she remains the gold standard for all playback singers even today. Similarly, Rafi sahab could sing for actors as diverse as Shammi Kapoor in Junglee and a melancholic Dev Anand as he sings “Kya se kya ho gaya, bewafaa tere pyaar mein”. The very nature of playback demands this ability to be a singing chameleon of sorts. Therefore despite the quintessentially pristine quality of Lata ji’s bell like voice, it cannot be cast in any one mould. Neither could Rafi Sahab’s. I am unable to agree with Sanjay Srivastav’a analysis of Lata ji’s voice in an article titled Voice, Gender and Space in Time of Five-Year Plans: The Idea of Lata Mangeshkar.

The rupture between folk/classical and the cinema aesthetic has to do, centrally, with voice cultures. As a practitioner, you almost consciously exemplify an older tradition: open-throated singing, coming from open spaces, the fields, the valley…. Are you reacting against a kind of tyranny of the ‘golden voice’?

No, not at all. Reacting against the suggested tyranny would mean a conscious, cultivated decision on my part to sound different. The truth is that even if I had wanted to, I couldn’t have sung in that ‘golden voice’ simply because I don’t have a ‘golden voice’. I just have a Shubha Mudgal voice which, with its inevitable limitations and strengths, was nurtured and developed by my gurus and which I keep examining and working on as I continue to study. To be honest, the tradition of Hindustani music gives students the freedom to find their own voice, which is why in every generation of vocalists, there have been voices with such diverse timbres and textures, such diverse aural personalities. What I have reacted against are the hierarchies and caste systems that exist in the arts, where classical arts are often considered superior as opposed to the folk and popular arts.

This is a bit out of context, but I find it interesting that you say I exemplify an older tradition. Not so long ago, maybe just over two decades back, Outlook re-used my photograph, shot by Gauri Gill initially for a feature on me, without my permission, for a special pull-out ad campaign for a travel company. I don’t remember the exact copy that was used with the photograph but it was to the following effect: “Want to do your own thing and tradition be damned? Shubha Mudgal did it, so can you.”

I sent the magazine and then editor Mr Vinod Mehta a legal notice and received a response which said it was meant as a compliment as I was exemplified as someone with an unorthodox approach.

But obviously perceptions do change!

While the landscape of Indian music changed in the 1950s in a way similar to what happened to dance with its nationalist redesigning—the earthier, more sensuous styles being pushed to the margins in service of the aspirational, revamped ideal—how do we rescue ‘folk’ from the image trap it is in now, as just exoticised specimens of a ‘diverse India’?

I think we would need a multi-pronged approach to do so. And any discussion on how to go about achieving this should involve the principal stakeholders themselves, leaders from among folk musicians. We need their direction instead of constituting expert committees that only include bureaucrats, classical musicians and culture czars and czarinas, however knowledgeable they may be.

Also, the support offered should not only be performance based. It should also address welfare schemes such as health insurance, insurance for musical instruments, taxation etc. Today, the film industry with its organised unions can approach the finance minister for bringing down GST rates on cinema tickets. There is no collective of folk musicians or, for that matter, classical musicians, that can approach the government for solutions, unless they find a mouthpiece with clout in high circles.

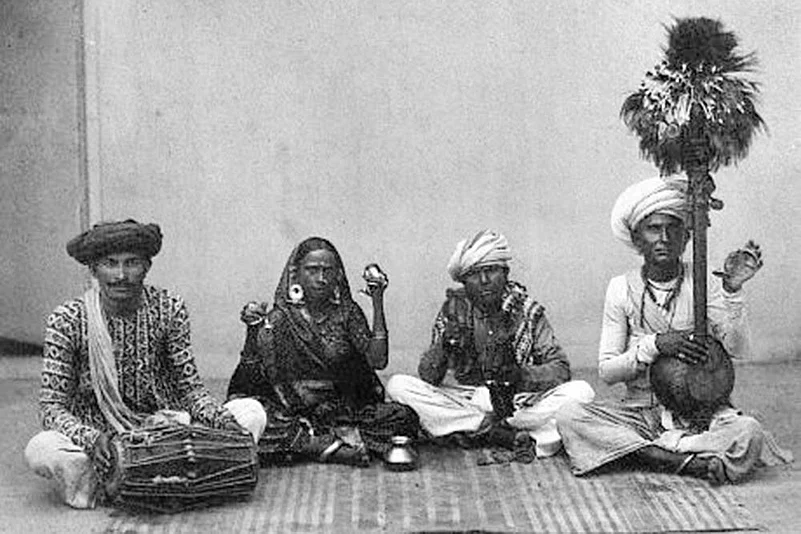

Folk musicians in Bombay, 19th century.

Did AIR and the music establishment in general—government or industry—consciously facilitate the upliftment of certain categories of Indian music over others?

Initially, AIR certainly promoted classical music more than other forms, even though its regular programming included folk music, geet, ghazal, bhakti sangeet etc. But credit must also be given to them for treating all forms with equality. Exponents of all forms of music had to audition, were graded, and based on the grade awarded to them, they received a broadcasting fee. An A grade classical artiste would therefore receive the same broadcasting fee as an A grade folk artiste. This remains a praiseworthy aspect of AIR policy.

In general, decisions taken by the government and its agencies are influenced by the party in power and its political agenda. For example, if the North Eastern states are to be wooed by the government of the day, in the sphere of art and culture, some funding for the arts may be sanctioned. Otherwise, no clear policy is articulated by the government with regard to music.

Would you say the earthier, timbrally richer styles are ultimately impossible to abolish? You see them filtering back into the mainstream in one guise or the other—the ersatz ‘folk’ singer of film, a qawwal like Nusrat...

Indian film music may include folk musicians or Qawwals or classical musicians in the occasional track as a novelty. But other than that, I do not foresee a more mainstream role for these genres.

It is only when audiences/listeners/consumers ask for more variety and are ready to put their paying power to test that a change may occur. For example, if a radio channel for folk music were to be started by some intrepid soul, would subscribers even pay a nominal, rock bottom subscription for it?

Does the converse also happen? Would you agree the pop/cinema aesthetic has infected classical and folk? Perhaps in the kind of voices we see now in classical, as opposed to the days of, say, a Krishnarao Shankar Pandit or an MDR? Or in the eruption of cheap studio versions in the case of the latter?

The use of amplification for live concerts as well as recording is largely responsible for the change in voice projection in classical music. Earlier, singers had to project their voices without microphones to reach everyone in their audience whereas now all concerts are amplified. In fact, many are amplified at ear-shattering decibels.

The short duration format of film songs has also influenced some classical musicians who believe that discarding the crucial element of detailed elaboration of and composition and presenting classical compositions/bandish with backing instruments like drums and guitars will be more attractive to listeners. So we are seeing many such renditions.