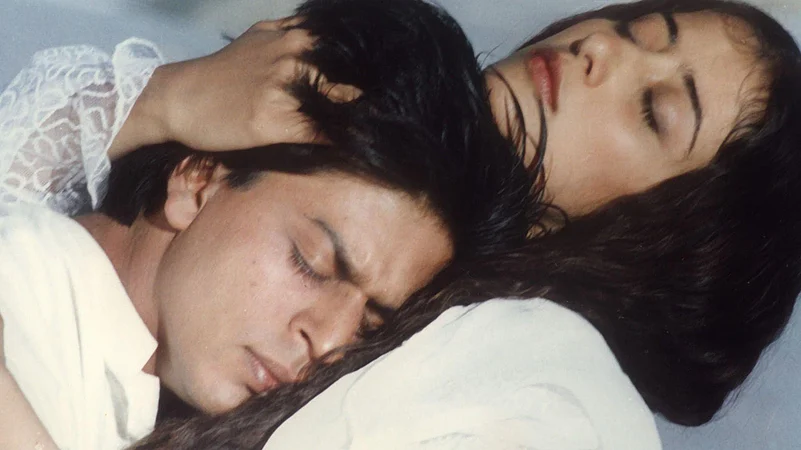

Mani Ratnam's Dil Se.. (1998) has been re-released in theatres to celebrate actor Shah Rukh Khan's 60th birthday.

The film features Shah Rukh Khan, Manisha Koirala and Preity Zinta in key roles.

This essay unpacks the unease of re-watching Dil Se.. in theatres and realising it is not just another SRK love story.

As the opening titles end, a frame appears—largely blue and mostly blurred. We hear the thunder and the strong gushes of wind that carry the rain with them, violently shaking what appears to be the branch of a tree. Within this frame, two orbs of yellow light glide along each other before moving apart. The camera lingers, allowing the frame a moment or two to exist as a quiet, dreamy, moody introduction to the sequence. Just as we begin to figure out that the two orbs of light are headlamps of a car, the camera pans to reveal barbed wires rattling in the wind. We are at a checkpost. An interaction occurs between the passengers and what are presumably Army officials, after which the car is given the green signal to go forward. As the car is moving away from the camera, the lens blurs the car’s body into orbs of different lights. But before the frame can dissolve, it is again interrupted with the barbed wires coming into view, lit by a caged work light.

This is the opening sequence of the theatrically re-released (perhaps for the first time) Dil Se.. (1998), a film immortalised by its soundtrack. Videos of people dancing to the song “Chaiyya Chaiyya” in the theatres are doing the rounds on social media. Much has been written on its music and its politics. This re-release, however, pushed me to think about where it falls within Shah Rukh Khan’s oeuvre, coming as it did in 1998, 50 years into India’s independence. Most viewers of my age arrive/have arrived at this film after listening to the songs or viewing the videos of the songs on music television channels or YouTube while growing up. The songs, if viewed outside of the narrative, might give the impression that they are expressions of a love story set in turbulent times. Many new viewers to the film, therefore, express unease, when it slowly starts to creep on them that this is not really a love story. Khan’s character Amar, an employee at All India Radio, appears to irritate and harass Manisha Koirala’s Meghna. His attraction to her seems forced and one-sided, which makes his attempts at a romantic relationship seem creepy, bordering on sexual assault. The theatre I watched this film in echoed this unease—each new song, placed as it is within the narrative—invited fewer and fewer hoots and cheers. The film, in a way, exceeded the context under which it was re-released (a film festival to celebrate SRK’s 60th birthday, featuring some of his other films). This article unpacks the specific nature of this unease. In some ways, the abstract opening sequence reveals this dance between beauty and barbed wires, and our unwillingness to see violence amidst beauty.

The film occupies an almost singular place in SRK’s filmography. This is not to say that he has not played unlikable characters. In Devdas (2002) and Kabhi Alvida Naa Kehna (2006), he has played entitled men with a chip on their shoulders. In Chalte Chalte (2003) and Hum Tumhare Hai Sanam (2002), he has played the parts of insecure husbands who doubt their wives. He has also played outright villains in Darr (1993) and Anjaam (1994), charming but obsessed lovers in Deewana (1992) and Maya Memsaab (1993), and the anti-hero in Baazigar (1993), Don (2006), and Raees (2017). In Fan (2016), he plays both the star and his obsessed fan, where he returns to the legacy of some of his psychotic roles. In all these films, however, any moral ambiguity present emerges from a clear motivational core. Dil Se.. unsettles because SRK plays Amar as a charming, upright, middle-class citizen, without any trauma or insecurities, ambitions or revenge missions. Amar’s antics with Meghna border on madness. During one of their interactions, he induces a trauma response in her, which is later revealed to be the response she had to her rapist. His madness is expressed through the songs, all of which, except “Jiya Jale”, clearly emerge from his own desires and not Meghna’s. But while the film is clearly drawing from the Sufi idea of destruction of the self in love, it does not fleece from the actual material context or the consequence of this endeavour.

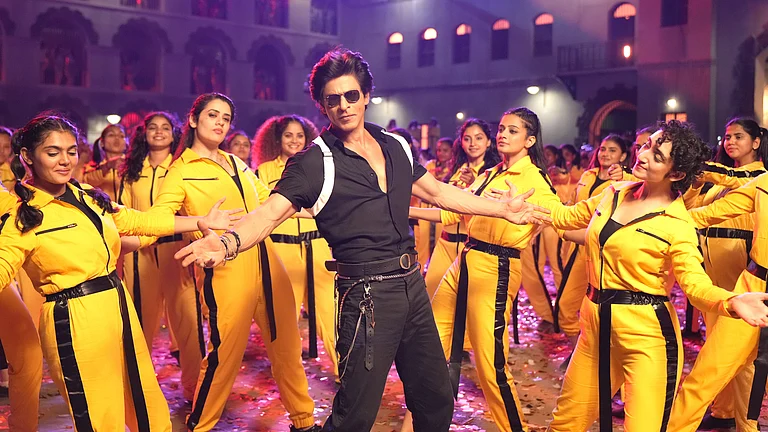

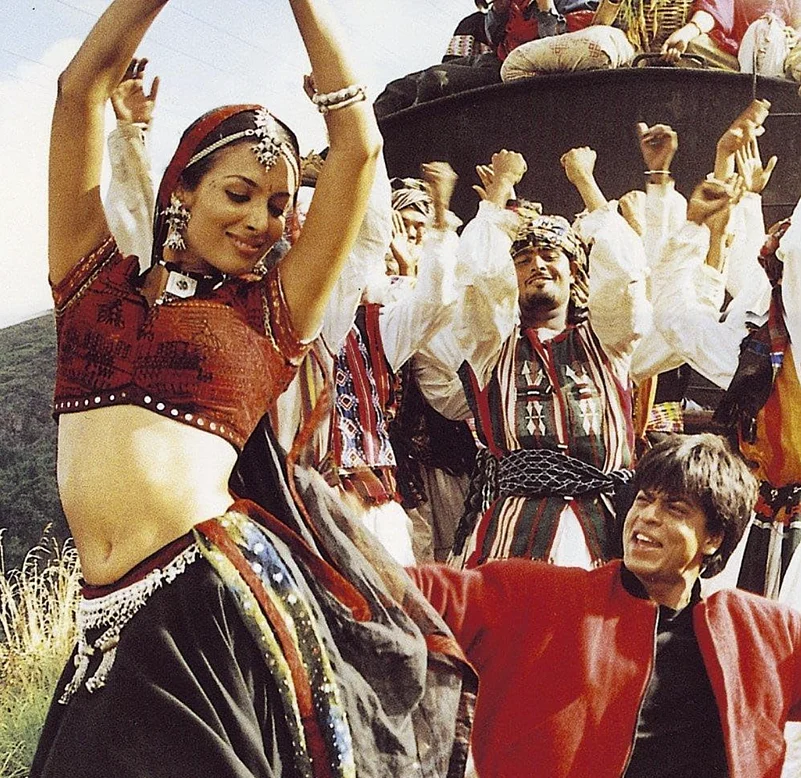

So, “Chaiyya Chaiyya” describes her as an object of desire—as a sweet smell, whose voice is as mesmerising as Urdu. The title song “Dil Se” emerges from his self-mythologisation of their relationship, where Meghna, who otherwise doesn’t smile, gladly falls into Amar’s arms, surrendering herself to him as the world literally is on fire around them. “Ae Ajnabee” is a singular call for connection between Amar, and the stranger he is infatuated with. “Satrangi Re”, which begins after he catches a glimpse of her bathing, is an expression of his conviction that they have become one unit. After she leaves him unannounced, in Ladakh, all his desires are frustrated, ending his fantasy-ridden ideas about their relationship. He goes back to living his ‘normal’ life, working for the state and receding into the familiar and the familial. “Jiya Jale", on the contrary, is the fantasy of the other woman, Preity Zinta’s Preeti (to whom he’s engaged), the only song in the film led by a woman (and sung by the late Lata Mangeshkar). The songs, all of them except the last one, therefore, accentuate the twisted nature of Amar’s advances towards Meghna. But because they are shot as such specific flights of fancy—“Chaiyya Chaiyya” on a train, “Dil Se” in a war-torn land, “Ae Ajnabee” played through the radio, and “Satrangi Re” across arid landscapes—they don’t repel. Their in-betweenness is a result of them being expressions of realms of desire—beautiful, stark, rhythmic and dangerous.

Amar has been characterised by academics such as Ananya Jahanara Kabir as a stand in for the violence of the Indian state, while Meghna a stand-in for the exoticised but oppressed people—in this case the different states of Northeast India. But less attention has been paid to how SRK’s stardom is mobilised in the film. In Dil Se.., he is both lover and abuser at the same time, deploying all the tools in his arsenal he had earlier honed as a romantic hero to great success in Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge (1995), Pardes (1997), and Dil Toh Pagal Hai (1997). It is this hero—a symbol of love, adored and upheld by the family and the nation and marketed as its best commodity—whose world is fractured with the arrival of Meghna in Dil Se.., a living archive of the failings of the Indian state. Amar, the romantic, fails to understand why Meghna just cannot love him, despite his charms and quirks, and his utter (performance of) devotion to her. His fantasy, captured through the title song is precisely that love can rise above violence without properly acknowledging it—a deliberate de-focusing of a picture draped in blood and gunpowder. But the barbed wire always rears its head. And a major reason for that is Meghna, who refuses to be subsumed in the love story he imagines for them.

Apart from standing out within SRK’s filmography, the film also differs in structure from Mani Ratnam’s Roja (1992) and Bombay (1995) in the ‘terror trilogy’. The previous two films have married couples at their narrative centres, whose lives are upended due to the actions of others. In contrast, the characters in Dil se—apart from the flashback revealing the massacre of Meghna’s village by the Indian army, and her and her sister’s rape—either directly engage in violence of their own or invite violence onto themselves. Meghna is a highly complex character, not only defined by her oppression, but also by her guile in navigating hostile environments. She drives the narrative forward in the second half of the film, when she turns up at Amar’s house, asking for a job at All India Radio and a place to stay. There is a wedding in this film too, but with a secondary character and not central to its plot. Within SRK’s filmography too, it remains the only film which flips the Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge template, where he isn’t the one with ulterior motives at a wedding, but the woman is. Her presence at the wedding generates anxiety for the viewer because it brings the possibility of violence within the home. This anxiety is even more heightened towards the end of the film, where the intelligence agencies close in on the one hand, and Meghna appears less and less inclined to carry out her mission on the other. In his quest to foil the militants’ plot and save Meghna at the same time, Amar is increasingly framed through a Hitchcockian lens of claustrophobia—attracting the wrath of both the militants and the Indian state. In the end, unlike the other two films in the trilogy, where the lovers separate and are reunited after their trials and tribulations, the two central characters in Dil Se.. become a unit only in their choice to die together, as they blow themselves up. The question of undoing the nation’s irreconcilable fractures is deliberately left unresolved.

Dil Se.. wasn’t considered a success at the time it released—its box office paling in comparison to the huge hits SRK had given in the previous years. In 2025, Dil Se.. arrives on the big screen with almost three more decades worth of our engagement with SRK’s public persona, where his trysts with the Indian state have diversified and become more complicated. Therefore, the denial of reconciliation, or a clear redemptive arc for SRK’s character takes on new meanings. So does conjecture about the lack of more such roles, with this shade of grey, in his filmography since then. For this reason, Dil Se.. feels like both an antecedent and outlier in SRK’s attempts at embodying the impulses of the Indian state.

Piyush Chhabra is a Ph.D Scholar of Cinema Studies at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. He works on the entanglements between law and different media forms.