Until Sachin Tendulkar travelled to Australia, India’s touring sides were viewed by the locals more as a group of men from an exotic land than an outfit to be treated seriously. Of course, the generalisation was grossly unfair towards a proud nation with a diverse and inspiring history—as well as being a production line for artistic cricketers. But it is all the more reason to praise Tendulkar. Not only did he create wide-eyed spectators with on-field deeds, but he opened minds away from the ground.

Instead of Test series with India being viewed as part of the interval between Australia’s major battles against England, South Africa and the West Indies, the engagements were quickly upgraded to marquee status from the middle of Tendulkar’s career. In the 44 years before his first Test against Australia, in Brisbane in 1991, the sides had contested 11 Test series. The recently completed campaign was the 12th in which Tendulkar had appeared against opponents wearing the baggy green.

Those dramatic schedule changes weren’t solely the doing of one man, but they wouldn’t have happened without him. And given the often patronising glances—or worse—at the Indians before the Tendulkar era, it was even more remarkable that he had swayed and besotted Australians of all beliefs. From those who guzzled on the Adelaide hill, to the blazer-wearing folk at the MCG, all the way to the nation’s top office. Last year, Julia Gillard, Australia’s prime minister, announced that Tendulkar would be presented with the Order of Australia, a rare civic accolade for a non-Australian citizen. The honour, she said, was a “very special recognition of such a great batsman”. It was also a tribute to cricket being “a great bond between Australia and India”. Again, Tendulkar’s role in this link cannot be understated.

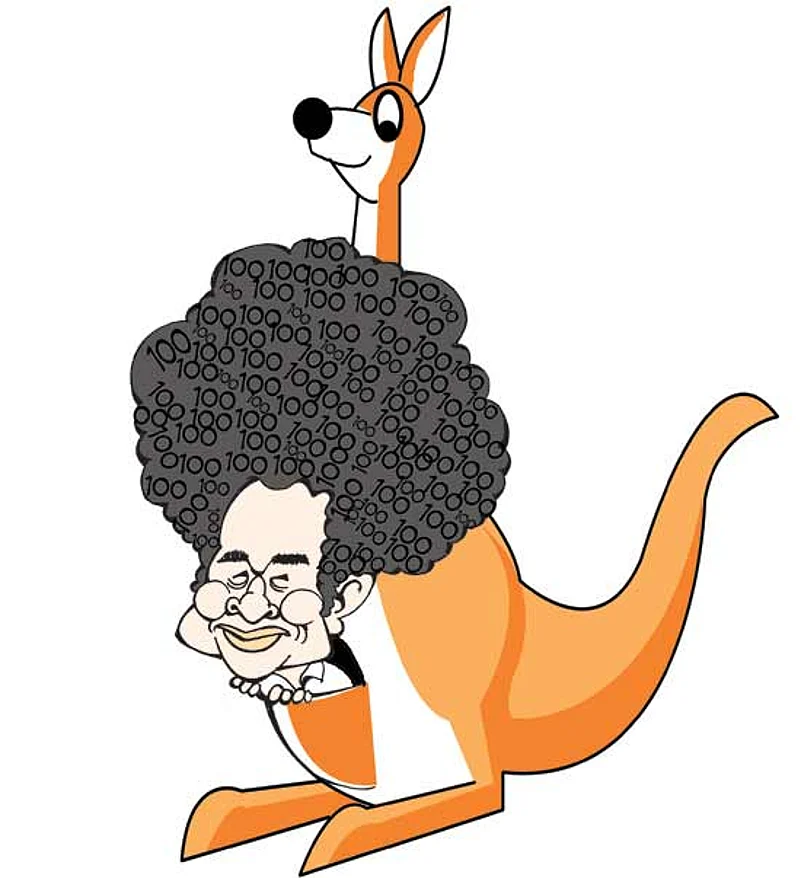

Even though he has been in the international game for almost 25 years, few cricketers have risen so high so quickly. With curls hiding behind his oversized helmet and pads rising almost to his hips, Tendulkar was just 18 when he first played Down Under. His sleeves were rolled neatly to the forearm, and as he waved his broad wand in the summer of 1991-92, he quickly established himself as a fearful-yet-fascinating threat. At the SCG, his unbeaten 148 was described by Richie Benaud, in awe in the commentary box, as “one of the best innings I’ve ever seen”. Shane Warne was on debut, looking more like a surfer than a spinner, and spent the first of many demoralising days wondering whether any type of deception was possible. The soon-to-be-greatest spinner was rarely lethal to the best batsman of the era. He would go on to dismiss Tendulkar only three times in 12 Tests. Anyone who could make Warne’s bowling impotent gained instant respect in Australia.

At the end of Tendulkar’s SCG innings, Dean Jones sprinted to shake Tendulkar’s hand. He had just become the youngest Test centurion on Australian soil, an innings definitely worth running to see. The following month, he finished the series with 114 at the WACA. This time, Benaud called it “the type of hundred that deserves a crowd of 100,000”. Tellingly, Tendulkar hit his pad in anger as he walked off, signalling to the world he would never be satisfied. A boy in body, he was already a superman in the mind. Merv Hughes teased Allan Border that his Test run-scoring world record was already in danger.

On India’s next visit, Tendulkar lured me to Adelaide for my first holiday as a full-time worker. It was a trip made with urgency, both in case his aching back forced an early retirement, and because of the uncertainty over when India would next return. It wasn’t his best series, but my trip was not wasted. Over the next couple of years, Australia would set a 16-match winning streak, but the instant memories from that Adelaide Test do not come from the deeds of Steve Waugh’s men. It’s Sachin—so small, so assured—dissecting Michael Kasprowicz for three fours in an over with no loose offerings. A hazy memory has distorted the order, but one was a clip in front of square, another just eased through mid-off. Then my favourite: a backfoot push along the ground through mid-on, the bat as straight as a ruler. None of the shots seemed to require any strength, the bat barely moving, the ball soon racing. Such beautiful battery. It didn’t matter that the punishment was directed at Kasprowicz, my favourite player. As Kasprowicz himself once said, “Don’t bowl him bad balls—he hits the good ones for four”.

Even back then, the crowds celebrated him as he attempted to floor their side. During that match in Adelaide, as the spectators in the Old Member’s stands roared, the rust-coloured rooves rattled and echoed in aesthetic appreciation. Had the Oval’s most famous batting Don been there, he would have again whispered in his wife Jesse’s ear asking for a comparison. And these emotions occurred during a “mere” half-century.

Disappointment and controversy followed in the second innings, when he ducked into a Glenn McGrath short ball and was ruled shoulder before wicket. Slightly shocked but dignified, he accepted Daryl Harper’s decision. At the end of the match, a 285-run defeat, Tendulkar spoke in his quiet way, explaining how he needed to “pull up his socks”, as captain and batsman, over the rest of the tour. The gentle self-admonishment seemed out of order, for there were few moments in Australia when anything he did could be considered unkempt. Even after his conflicted role in the Monkeygate scandal and his almost silent trip in 2011-12, he was still adored by a legion of supporters. Following his own advice, he registered a hundred and another half-century in the next match in Melbourne.

On his next Test visit, in 2003-04, he was on the way to 241 at the SCG when he drove a group of Australian fans to the beach. Occasional supporters who wanted to see the home side dominate, these guys grew tired of the pummelling and adjourned to Bondi. Meanwhile, in the Member’s Pavilion, the aficionados were able to savour his 353-run stand with V.V.S. Laxman. More joy came to them four years later with another Tendulkar epic, but this century was overshadowed by the fallout from a contentious, ill-tempered contest.

That series might have been the end of his playing relationship with Australia. Age-old slang marks out one who has more goodbyes than Dame Nellie Melba, an opera singer reluctant to leave the stage. On Tendulkar’s past two trips to Australia, in 2007-08 and 2011-12, the “farewell” ovations across the country were so sustained that a pernickety official could have considered a rash of timed-out rulings.

Only a handful of visitors have managed to crack the code for unfettered adulation from Australian crowds. To the cricket cognoscenti, Tendulkar sat comfortably among them; yet he was also appreciated by the masses. Matthew Hayden was a relentlessly hard-nosed and fierce-lipped opponent, but even he, a previously devout Catholic, was converted to a new religion. “I have seen god,” Hayden said, “he bats at No. 4 for India.” In painting Tendulkar as his favourite player, respected sports writer Greg Baum also looked on high. “Here is a man whose name is synonymous with purity, of technique, philosophy and image.... Tendulkar is surely the game’s secular saint.”

For all his trips to Australia, it was a short visit as a tourist that remained Tendulkar’s favourite. To mark Don Bradman’s 90th birthday, he and Warne went to Holden Street in the Adelaide suburb of Kensington Gardens for a short celebration. Both nervous, in suit and tie, both about to be inspired. Even greats have their heroes. “We just stood beside him and allowed him to talk as much as we could because we wanted to hear him,” Tendulkar recalled last year. Bradman was dressed in a well-worn cardigan and the occasion was sealed with a trio of signatures on a very lucky bat. Most spectators have Tendulkar’s batting signed in their minds.

Treasured cricket journalist Mike Coward wrote of the beauty and pain of watching him during his “first” farewell series in 2007-08. Despite the age and inaccuracy of the description, it remains hugely relevant—and delightful. “It is never easy to say goodbye to someone who has graced the game in such a manner and brought great joy. There is a sense of privilege at having lived in his time but, at the same time, a deep regret that he won’t be back again.”

Of course, when Tendulkar does retire, the emotions will be felt across the cricket world. But there will always be a special place for him in Australia, a land in which he altered the game in many ways.

(Peter English is an Australian sports journalist and academic. He writes for cricinfo.com, Wisden, Wisden Cricket Monthly and the Guardian.)