Summary of this article

Cybercafé operators, NGO workers, officials, and brokers now function as the real welfare infrastructure

When benefits do not reach people, responsibility dissolves across portals, departments, and protocols

Efficiency achieved at the cost of dignity is not reform. It is abdication.

India’s digital welfare system is often presented as a quiet administrative success. Aadhaar-linked transfers, online portals, biometric authentication, and real-time dashboards are said to have reduced leakages, improved targeting, and made the state more efficient. In this narrative, technology is a neutral upgrade—cleaner, faster, and fairer. But from the perspective of those who actually depends on welfare, digitisation has done something far more consequential. It has reorganised how responsibility, risk, and accountability are distributed between the state and citizens. Welfare has not simply gone digital; it has become a test of endurance.

Based on fieldwork with welfare beneficiaries in Srinagar, Jammu, and Kashmir, our research shows that digital welfare in India operates less as an integrated system and more as a fragmented governance architecture. People do not encounter “the state” through a single interface. Instead, they must navigate a stack of disconnected systems, say, Aadhaar authentication, bank linkages, scheme portals, biometric devices, and automated SMS alerts—each governed by different rules, timelines, and authorities. When something fails, and it often does, there is no clear institutional owner of the problem.

This fragmentation is not accidental. It performs a political function. By dispersing welfare delivery across platforms and departments, the system recentralises control while shifting the burden of coordination onto beneficiaries themselves. The state becomes omnipresent in data and verification, yet elusive when accountability is demanded.

For welfare claimants, this translates into a cumulative administrative burden. Every update, re-verification, or unexplained error consumes time, money, and emotional energy. A welfare claimant who receives a cryptic SMS does not know whether it signals routine information or imminent suspension of benefits. A labourer whose biometric authentication fails is told to “try again later,” with no explanation of whether the fault lies in the system or with the labourer himself. Over time, this uncertainty produces anxiety, fatigue, and withdrawal. Importantly, these are not side effects of just poor design. They are governance outcomes. Emotional exhaustion discourages claims, delays grievance-seeking, and quietly filters out those least able to persist. Non-take-up is not merely a matter of ignorance or apathy; it is produced through repeated friction.

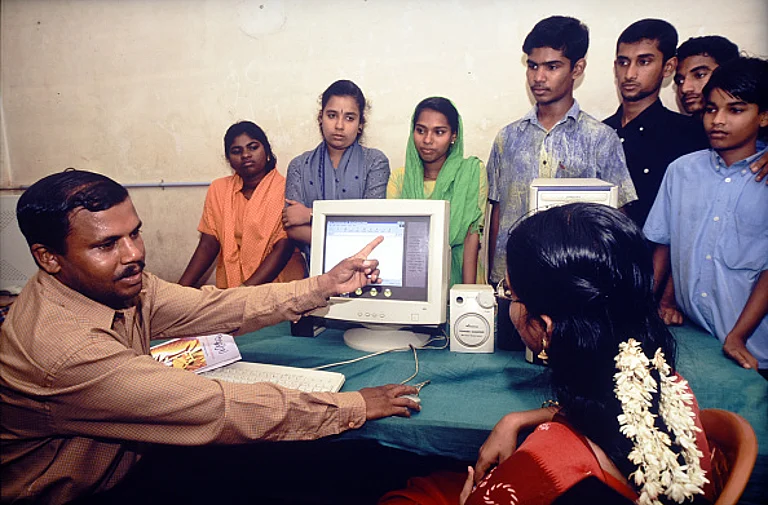

Digital welfare also reshapes who does the work of the state. Despite claims that technology eliminates intermediaries, it has made them indispensable. Cybercafé operators, NGO workers, local officials, and informal brokers now function as the real welfare infrastructure. Beneficiaries routinely share passwords and one-time codes, not out of carelessness but necessity. Privacy and security are traded for access because refusal means exclusion. This is a crucial shift. Risk has been transferred downward. When systems fail, the cost is borne by citizens, not institutions. Entitlement is no longer just about eligibility; it depends on one’s capacity to manage complexity, absorb uncertainty, and endure repeated verification.

These dynamics are evident in Jammu and Kashmir, where patchy connectivity, periodic communication disruptions, and administrative instability magnify digital burdens. But this does not make the region exceptional. It makes it revealing. Srinagar shows us what digital welfare looks like when infrastructural and political cushions are thin.

What is often celebrated as efficiency is, in practice, a form of governance through uncertainty. Fragmentation allows the state to audit, monitor, and verify without fully owning the consequences of failure. It creates plausible deniability. When benefits do not reach people, responsibility dissolves across portals, departments, and protocols. This has profound implications for citizenship. Welfare has historically been one of the most tangible ways people experience the state. Even flawed face-to-face bureaucracies allowed explanation, negotiation, and human accountability. Digital systems replace these encounters with automated messages and opaque processes. Citizens become more visible to the state but less able to engage it meaningfully.

None of this is an argument against technology. Digital systems can and should improve public service delivery. But treating digitisation as a purely technical reform obscures its political effects. Without coordination across platforms, human support at points of failure, and clear lines of responsibility, digital welfare risks becoming exclusion by design. The real question, then, is not whether digital welfare saves money or reduces leakages. It is whether a system that makes the poorest citizens responsible for managing state failure can ever claim to be inclusive.

If welfare is meant to provide security, it cannot operate as a continuous test of endurance. Efficiency achieved at the cost of dignity is not reform. It is abdication.

Views expressed are personal

Dr Abdul Mohsin is a political researcher whose work focuses on poverty, welfare, and everyday experiences of marginalisation. He holds a PhD from Aligarh Muslim University and completed his postdoctoral research at the University of Hyderabad.