Three other scholars whose names I cannot pass over in silence, are the late R. D. Banerji, to whom belongs the credit of having discovered, if not Mohenjo-daro itself, at any rate its high antiquity, and his immediate successors in the task of excavation, Messrs. M.S. Vats and K.N. Dikshit…

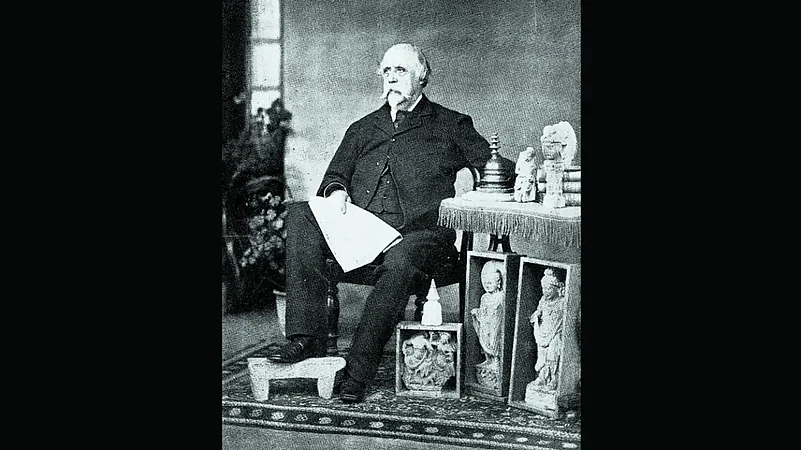

John Marshall

Director-General (1902-28)

Archaeological Survey of India

For more than 150 years, the discovery and subsequent excavation of the ruins of Mohenjo-daro since the mid-19th century have remained a crowning glory for the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI)—founded by the British but driven by Indian field officers working diligently and meticulously in their search for the truth. The report on the discovery of the Harappan civilisation, it is said, was written over three decades—and remains a testimony to the painstaking effort put in by the ASI to analyse every piece of evidence before they became part of the official records.

Fast forward to 2003. On August 22, the ASI submitted a 574-page report to the Lucknow bench of the Allahabad high court on its excavations in Ayodhya to verify claims about a Hindu temple beneath the then-destroyed Babri Masjid. The report was compiled within 10 days of the completion of the survey on August 12. Obviously, the two sites cannot be compared as the former was a vast area with thousands of artefacts. Also, with modern technology and equipment, the ASI is in a position to work much faster than it was ever before. But even then, critics and a section of the archaeological community were aghast at the ASI’s rush to submit its report.

History has invariably influenced the shape of the modern nation-states. And the past has always had a bearing on the present political ideologies. Thirty years after Babri Masjid was demolished, new flashpoints have emerged in some parts of India with many Hindu organisations staking claim on Muslim monuments and places of worship which were allegedly built over destroyed temples. Drawn into this clash of ideologies is the ASI, which has found itself mired in controversy and criticism—most of them hurled by political opponents of the ruling BJP at the Centre.

A questionnaire sent to the ASI director-general on the allegations and criticism went unanswered till the time of going to print.

Past and present

ASI experts, past and present, admit that politics does influence their work to an extent but they also add that it is not a new trend. Former employees of the ASI Outlook spoke to say that the organisation has been under pressure from all governments. According to one of them who retired over a decade ago, the organisation has been strongly influenced by the political classes that emerged post-1947. “After this period, the pressure increased and the brief was for findings connected to ethnicity and religion. There was a clash between archaeological research and ground reality. This has continued,” he says. This is probably the only department whose investigations and findings create tensions, says a former ASI director-general. “There is a close link between religion and archaeology and the ASI is helping establish it,” he adds.

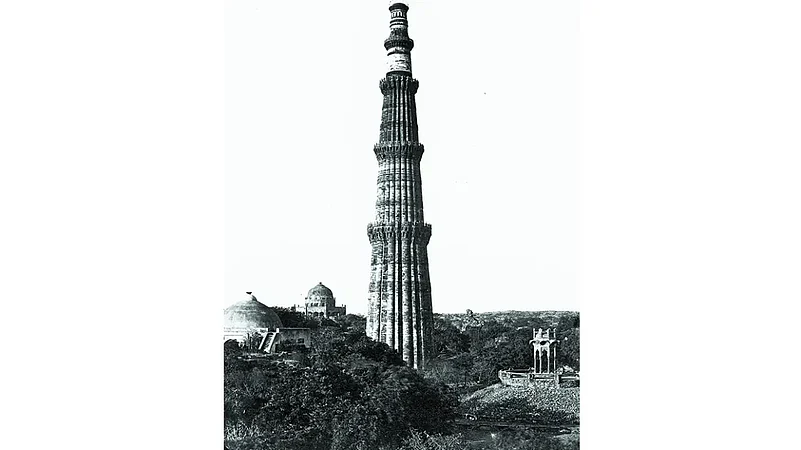

Speaking on the condition of anonymity, serving ASI officials say that despite political influence, the organisation’s work has always been guided by evidence. Take the case of the demand for allowing prayers at the Qutub Minar complex in Delhi, one of them says. On May 24, the ASI told a Delhi court that the Qutub Minar has been a protected monument since 1914 and its structure cannot be changed now. “The revival of worship cannot be allowed at a monument where such a practice was not prevalent at the time of it being granted the ‘protected’ status,” the ASI said. The Centre has already asked the ASI to carry out a survey in the Qutub Minar complex following demand by a Hindu group to conduct prayers in the protected monument. Earlier last month, the ASI put up in public domain photographs of the sealed rooms in the Taj Mahal premises to scotch speculations after Hindu groups demanded their reopening to look for possible signs of Hindu heritage.

Faith over fact?

Some ASI officials, however, do not deny that there is “more pressure” on them as the right-wing seeks to revisit and reconstruct history from the Hindu viewpoint. “The ministry of culture, the parent body of the ASI, is focused on excavations at sites built by the Mughals because it believes that these were Hindu religious sites before. The ASI is the tool to deliver,” says a source. The ASI is caught in a quagmire of political, social and nationalistic pressures, says a source who has followed the shifting ideologies of the organisation over the years. “There was pressure when the Congress held power at the Centre, but in the present government’s politics, the ASI is definitely playing an important role,” a former head of the ASI tells Outlook.

The ASI became a much more familiar name to the general public after the 2003 excavations carried out at the Ram Janmabhoomi–Babri Masjid site in Ayodhya. The excavation to unearth a Hindu temple buried underneath the Babri Masjid had caught the attention of the nation. Fifty-three personnel from the ASI, 131 labourers and others had excavated the site at Ayodhya from March 12 to August 7, 2003. Police and paramilitary personnel protected the ASI team, while the Public Accounts Committee kept a close watch on the happenings, say sources. “We did not know what we would find but we were tasked to find the remnants of Hindu gods,” says another source. This challenging excavation was done in two shifts–day and night. The team had found all sorts of things—pottery shards, burnt bones, tiles, terracotta pieces, fragments of unknown idols etc.

In normal course, excavations carried out by the ASI are unhurried, done over years slowly, often at a snail’s pace. “Analysis of all that is found at sites takes a very long time. We have to establish the periods and the age of the discoveries we make. This is the reason that reports are endlessly delayed,” says an ASI expert. “However, in the case of Ayodhya, the report was completed and presented to the court in 10 days,” the expert adds.

In the Taj Mahal case, a public interest litigation was filed in the Allahabad high court stating that idols of Hindu gods have been locked up in the closed chambers of the World Heritage Site in Agra. This petition—filed by Rajneesh Singh, the media in-charge of the BJP’s Ayodhya unit—has demanded that the ASI should open these 20-odd rooms in the Taj Mahal. “This has become a new trend now. Some right-wing organisations file a case against Mughal monuments seeking that ASI should be directed to excavate it to find out if they were built after razing Hindu religious structures,” says another source. The ASI can pilot largescale excavations as it is the premier archaeological organisation in the country. In 2002, when the NDA was in power the ASI launched the Saraswati Heritage Project, which was a multi-disciplinary study of the river, considered holy by Hindus. After the BJP lost the elections in 2004, the Congress-led UPA government stopped this project. However, it was revived by the ASI after the BJP-led NDA came back to power in 2014.

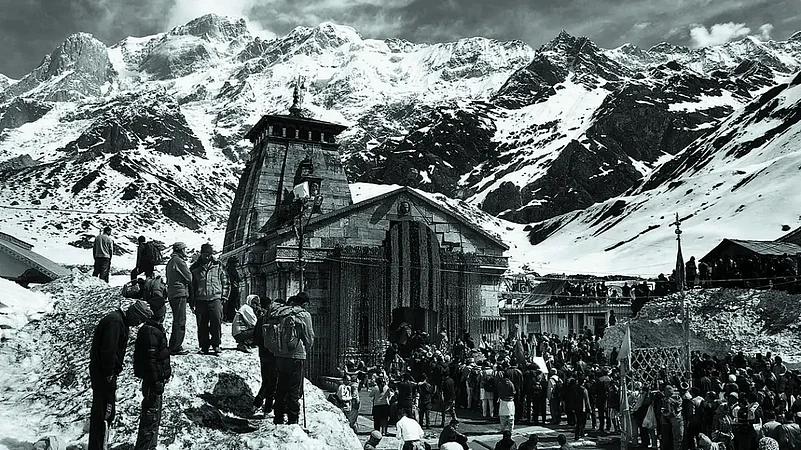

In 2014 too, the ASI had courted controversy over “hurried” restoration work on the Kedarnath Temple post the devastating floods of 2013, which had destroyed parts of the temple. The then president of the Badri Kedar Temple Committee had criticised the work of the government agency and had said that the ASI should adopt a transparent and efficient approach and make good use of the government money. Outlook spoke to a number of archaeologists from various parts of the country and most of them were unanimous in their criticism of the ASI. According to one, the ASI is a “conservative organisation that is unmanoeuvrable”. An archaeologist from Gujarat says that “this is a government organisation run by bureaucrats and is politically controlled by the government. The Central government lays down its agenda and the ASI follows it. After all, bureaucrats fall in line with the government of the day.”

ASI was founded in 1861 by Alexander Cunningham who became its first director general and archaeological surveyor. In 1958, it was brought under the Union Ministry of Culture through an Act. The ASI conducts archaeological research and protects the archaeological heritage of India. The workforce of the ASI includes trained archaeologists, conservators, epigraphists, architects and scientists for conducting archaeological research projects.

Despite its frequent brush with controversy, the ASI has stood as the gatekeeper of India’s antiquity, restoring and preserving monuments that are visited by millions of people from across the world. Across the length and breadth of the country, faceless and nameless workers continue to dig, scrape and brush away layers of dust to bring to light some of the most glorious periods of the country’s history and prehistory. And despite shifting political ideologies, the ASI remains the strongest link between the past and present.

The truth is out there. And someone, somewhere is working to unravel the truth. One ancient brick at a time.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Seek and Ye Shall Find")

Haima Deshpande in Mumbai