As a child, whenever I lay in the veranda for an afternoon siesta, I used to hear a roar-like sound from somewhere. My grandmother would tell me that it was Vibhishana calling out Ram in agony because of a stomach ache that Ram gave him after killing Ravan and enthroning him as the king of Lanka. When Vibhishan wriggled in pain, Ram told him, “If you cry Ram-Ram loudly, the pain will go away.”

Almost till my cynical teenage days, I heard it quite often and never refused to believe the tale. Another story says that when Ram decided to accept Sita for the second time, after abandoning her, she cried and called for her mother Earth, which split into two, took her in and she disappeared underneath. When Ram furiously grabbed her hair, he got only a handfull. Ram then threw her hair over the fence, which grew into a plant and later came to be known as Sita’s hair. Today, this is a good medicinal plant used for hair growth.

This kind of validation of culture through storytelling is a function of folklore. Every Indian child went to sleep praying to Hanuman, to wake him up by hitting him with his tail and not allowing him to be afraid, when he had a nightmare at night. Like this, as a story, as a play, as a shadow, the Ramayana lives with every Indian. On an average, there are at least eight versions of the Ramayana in each Indian language. It is not limited to the continuation of the Vedic literary culture. Different versions of Ram stories can be found in the same village, which have been told, written, sung, danced and enacted. It is this multiplicity that makes the Ramayana an epic of everyone.

ALSO READ: Who Is Ram And What Is His Story?

Not limited to devotion to Ram

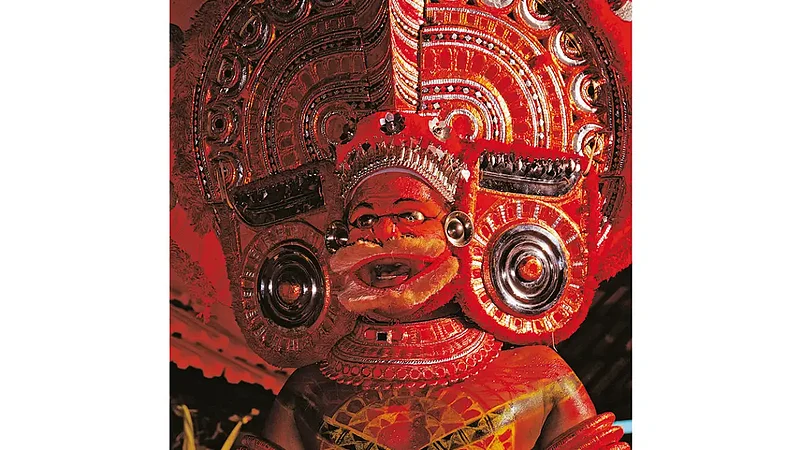

In Kerala, the Karkidakam of the Malayalam month (July–August) is observed as the Ramayana month when Adhyathmaramayanam Kilippattu, the most popular version of the epic, is read in every home. Kilippattu in Malayalam means a story told by a parrot. As a revolt against the upper class, who possessed and refused knowledge to the lower castes, poet Thunchat Ezhutchan wrote it in the 16th century.

The rendition ends with Pattabhishekam, the crowning ceremony of Sri Ram. But the Ramayana cannot be limited to the perspective of devotion to Lord Rama. It always interacts with time and land, challenging its own myths and logic, and keeps on updating itself with the present value systems. The Ramayana is ultimately a human story and that is why Ramayanas are as diverse as human beings.

ALSO READ: Who Is Ram? Defining The Enigma

Bhakti, or devotion, is only a part of the epic. It deals with many outlooks beyond devotion. Anthropology, nature, agriculture, gender justice, mythology and knowledge, among many issues, come into play in the Ramayana. It is political too. Many moments of subtle debates on political correctness remain unnoticed in the Ramayana. In the Valmiki Ramayana, ‘Aranya Kandam’ 6th Sargam talks about the sages who meet Ram at Dandakaranya during his journey through the forest along with Sita and Lakshman. They complain to Ram that the rakshasas are bothering them a lot. Ram, in turn, promises them that he would kill the rakshasas. Later, Sita reacts by gently warning Ram about a possible genocide that will follow.

“You have promised the sages. Therefore in the forest Dandakaranya, wherever you see a ß you may shoot arrows at him. Why do you kill them without any previous enmity? The forest is their home. You are an armed kshatriya. If you take a weapon, your intellect will be corrupted. You will get intoxicated with violence. I think it is better to follow kshatriya dharma after your return to Ayodhya. This is the forest and the life and values here are different. Isn’t wisdom appropriate here? I am only gently reminding you, not advising you,” Sita tries to correct Ram, who has nothing to say except express his helplessness, “I promised them…”

In Adiya Ramayana, a tribal version in Kerala, Hanuman does not like Ravan calling him a monkey. Hanuman takes it as a racial insult and feels like burning Lanka to ashes. There seems to be no other literary work that has done as much democratisation of knowledge as the Ramayana.

The Mappila Ramayana was sung by a folk singer called Hasanar in Kondotti, a town in North Kerala. Author and scholar T.H. Kunjiraman Nambiar collected and published this oral Muslim version of the Ramayana. In this version, Raman is given the Muslim pronunciation of regional slang, ‘Laman’. Surpanakha tells Ram, following the rules of marriage in the Islamic religious code, that even if he has a wife, he can marry her too. There the plot of the Ramayana itself is venturing into an Islamic precinct.

One place, many Ramayanas

Similarly, Wayanad has a great tradition of rendering various versions of the epic, as mentioned in Aziz Tharuvana’s Wayanadan Ramayana. Folk versions like Adima Ramayana, Wayanad Chetti Ramayanam and Wayanad Sitayanam make characters from the landscape, plants, rivers, agriculture, customs and beliefs of Wayanad. They believe that Wayanad was created by Mayan, father of Mandodari. Sita, who was walking up and down the hill and mountain with baskets and pots, stopped and gave way to the wayfarers Ram and Lakshman. Her polite demeanour makes Ram feel an insatiable desire for Sita.

According to these versions, the group led by Hanuman in search of Sita, who was abducted by Ravan, reached Lanka via Pakshipathalam, Tirunelli, Mananthavadi, Pongini, Mutil, Puthurvayal, Mepadi, Meenmutti, Anapuzha, Nilambur, Mannarkad, Palakkad, Pollachi, Palani, Madurai and finally Rameswaram. This route map very well matches with the logic of the folklore, time and places. It is from Rameswaram that Hanuman flies to Lanka.

In the folklore of Wayanad, Valmiki’s ashram is at Ashramkolli near Polpalli in Wayanad. The lake in Ponkuzhi is where Sita’s tears fell. The water in the Kannaram river, where Sita bathed in turmeric, is still yellow in colour. In their Ram story, Luv and Kush tied Ram’s yagaswam near Ponkuzhi in Wayanad and the statue of Sita made for Ram’s rajasuya yajna is not of gold, as Valmiki says in his Ramayana, but of wheat flour. Jatayatakavu is the place where Ram held Sita by her hair, when the earth split and Sita disappeared. That is how the Wayanad Ramayana stories go. Attappadi Sri Ramakushalava drama is popular among the Irular tribal people.

Kerala has a traditional theatrical art form called Kootiyattam, the most ancient living Sanskrit theatre tradition, claimed to be 1800 years old. They performed Ram Katha as Kootiyattam drawing upon the script of the 1st century playwright Bhasa, who wrote 13 plays, with stories Abhisheka Natakam and Prathima Natakam based on the Ramayana. These stories are still actively enacted by the Kootiyattam performers in Kerala. The folk music and dance traditions like Kolkali and Chuttukali among the tribal communities like Malluva Kurumar and Mandadan Chetty have also played a major role in the creation of the Wayanad Ramayana.

Sustaining on a vast folklore culture

It is interesting to note that the most comprehensive and authoritative study of the origin and development of Rama Katha was done by Jesuit priest Camille Bulcke. Born in Belgium, Bulcke came to India in 1925 as a Christian missionary and moved to become a scholar of Sanskrit and Hindi. His thesis Ram Katha: Origin and Growth is considered one of the most authentic studies on the epic. According to Bulcke, the original Valmiki Ramayana has three textual versions, Dakshina, Goresio and Western. He finds different interpretations of stories of Valmiki, Ravan, Sita and all other characters in the Ramayana, as he carefully interprets myths and hearsay from the perspective of anthropology.

ALSO READ: Lesson On Environment From Ramayan

Ram Katha never ends with the Treta Yug as it extends to the next yug, Dwapar. The lore has it that when Pandavas and Draupadi were doing their stint of vanavas, living secretly in exile, they happened to cross a river in a boat and saw an iron ring lying there on the shore. It was large enough for Bheem to pass through without his body touching it. The boatman tells them that it is Sita’s toe ring. Thus, the Ramayana sustains on a vast folklore culture spanning an entire continent. It is this multiplicity, not monotony, that makes the Ramayana popular. The various renderings that the epic has spawned over the centuries have always been enriched by conflicts and attitudes, rather than obeisance and submission.

(This appeared in the print edition as "As Diverse As Humans")

(Views expressed are personal)

Keli Ramachandran Is a mumbai-based art organiser and documentary film maker