Prescriptions are generated in seconds, consultations are cursory, ‘doctors’ are sometimes untraceable, and repeated purchases of controlled medicines raise no alarms

India has no law explicitly permitting online medicine sales—and none banning them.

All medicines ordered by Outlook were Schedule H1 drugs.

This market should not exist, at least not in its current form.

The proliferating market of ten-minute online medicines delivery has little checks and balances, and even little concern for public health and safety.

The annexures prepared under India’s Drugs and Cosmetics Act, medicines classified as Schedule H1 — antibiotics, antidepressants, and strong painkillers — are meant to be dispensed with Medical Prescription Caution/Warning. The law and Schedules H1 thereto mandate a valid prescription, recorded sales, doctor’s judgement, pharmacist supervision, and traceability of both the prescribing doctor and the patient as well as distributors and pharmacies.

These safeguards are not bureaucratic hurdles; they are for public -health protections designed to slow access, prevent misuse, and reduce harm.

Yet today, these very medicines are being delivered in less than ten minutes.

Outlook’s investigation revealed that some online platforms such as Blinkit, Apollo 24/7, and others are effectively operating a parallel pharmaceutical market — one that treats prescription drugs like convenience goods and medical oversight as a formality.

Medical Prescriptions are generated in seconds, consultations are cursory, ‘doctors’ are sometimes untraceable, and repeated purchases of controlled medicines raise no alarms. The findings suggest gaps in oversight that could compromise standard prescription protocols, raising public health concerns.

“There are three aspects,” says Bejon Misra, consumer policy expert. “Inefficient regulatory oversight, outdated laws—drafted in the 1950s—which have no provision to control or monitor the online model, and no deterrent or penalties to these platforms to ensure they follow proper norms.”

Misra, who has been involved in consumer rights and protection for decades and worked with Jaago Grahak, expresses shock and concern that Outlook was able to buy not just antibiotics and painkillers, but also antidepressants, without any checks, and with multiple orders placed within 12 hours.

When Access Becomes Abuse

Medicines of all classes—antibiotics, antidepressants, NSAIDs, steroids—require careful prescribing by a qualified doctor, says Dr Sanchayan Roy, senior consultant in internal medicine, who runs his private practice in South Delhi.

He explains that prescribing decisions depend on clinical history, allergies, diagnosis, and follow-up. “Some drugs can be started in the first consultation like Paracetamol and some mild painkillers for immediate relief,” he says, “while psychotropic drugs often require longer monitoring.”

Online platforms routinely bypass this process, with little care over why a person might be buying such heavy doses of drugs so quickly.

Here is an anecdote that illustrates the abuse of anti-depressants without prescription. A few years ago, an 18-year-old in Patna was prescribed Nexito (escitalopram) after being diagnosed with anxiety and depression. The medicine worked. He described the effect as “comfortably, ignorant, dumb bliss.” But after a couple of months, it began affecting his memory, and he stopped.

The pills did not remain unused. They circulated among his friends—an easy, prescription-free route to the same “bliss.” Soon, stronger substances followed. What began as legitimate treatment quietly turned into misuse.

This is how prescription abuse often starts—not with criminal intent, but with easy access.

For this story, Outlook was able to buy Escitalopram from Apollo’s online store, without any prescription. More details from the Apollo delivery experience will unravel later in this story.

Dr Jateen Ukrani, a psychiatrist practicing in Delhi elaborates on this: “Escitalopram, like Nexito, is an antidepressant and anti-anxiety medicine used for anxiety, depression, phobias, and sometimes OCD. It is not a one-time painkiller, and irregular use can increase side effects.”

When asked if this can be harmful or be abused, he explains changes for addiction are low in escitalopram but compared to other antidepressants, but even paracetamols can cause damage the liver when taken in excess. As for prescribing these medicines, a doctor must meet the patient or at least have a thorough consultation.

Ten-Minute Delivery, One-Minute Medicine

Ten-minute delivery has already transformed how Indians buy vegetables, groceries, dairy, and electronics. Medicine was the inevitable next step. Platforms like Blinkit and Zepto entered the space promising “free medical consultation” and rapid doorstep delivery.

On paper, the model appears helpful: consult a doctor, get a prescription, receive medicines at home while unwell. In practice, Outlook found the system dangerously superficial.

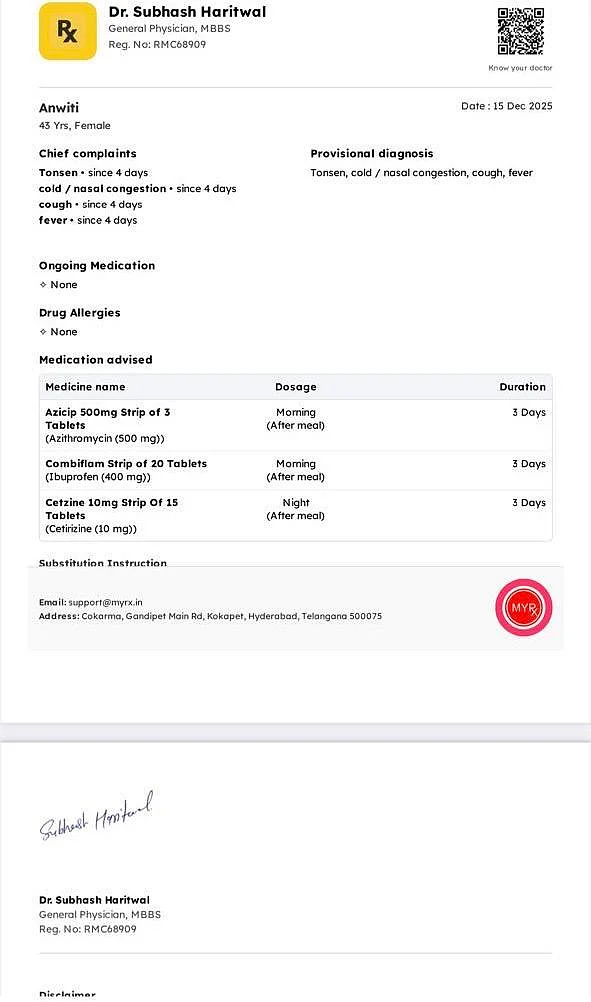

Outlook placed multiple medicine orders on this platform. Each time, a “doctor” called within seconds of payment. The consultation involved only a few questions: patient name, age, allergies, and reason for medication.

Of the four e-prescriptions issued by Blinkit, Outlook searched the National Medical Commission registry and could not locate the names or registration numbers of two of the four doctors listed. Lawyer and cybersecurity expert Pavan Duggal says unless it is a tech glitch on the website, a prescription with any inaccurate information on the doctor is violative of regulatory norms.

Outlook reached out to Blinkit for their responses. Not just on this oversight, but on how their model works. However, its communication team declined to comment or answer our queries.

Delivery no bar

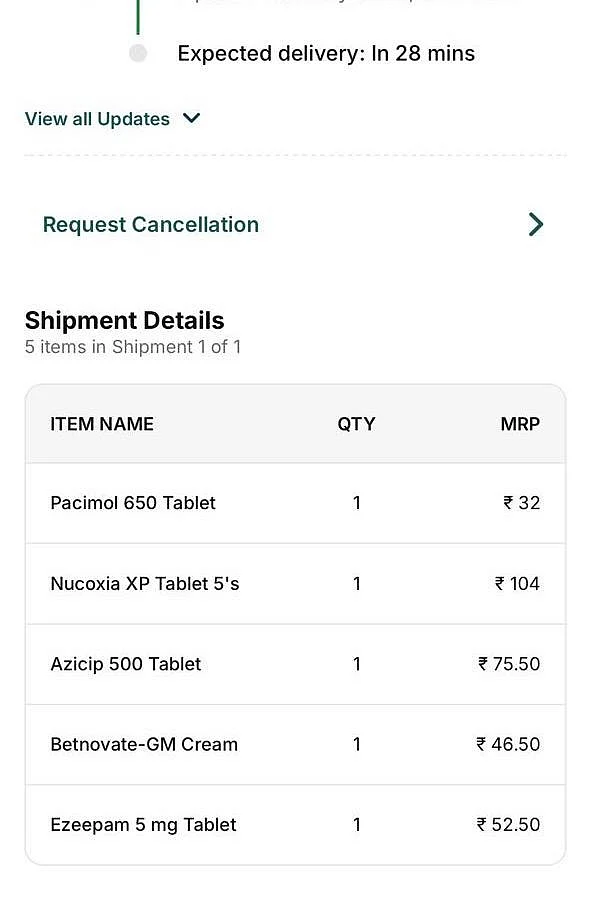

As part of our story and to examine the ease of getting instant medicines, no questions asked, Outlook deliberately gave different reasons during different calls: Delhi air pollution causing throat irritation, a broken leg from a couple of months ago, severe viral infection, not feeling too good. The medicines delivered included Cetirizine, ibuprofen, azithromycin, aceclofenac, etoricoxib, escitalopram and more. Many had little or no relation to the ailments described.

Yet every order was approved within roughly 30 seconds and delivered within 10–12 minutes.

We repeated the process less than 12 hours later. The questions remained unchanged. No one flagged the repeat purchases. No one asked about prior prescriptions, ongoing treatment, or cumulative dosage. A single user was able to buy thousands of milligrams of painkillers and antibiotics in under a day.

When we reached out to Apollo they claimed their system was robust and no scheduled medicines could be delivered without oversight. They claimed the example cited above was an aberration rather than the rule.

Schedule H1: Brick and mortar pharma sales

All medicines ordered by Outlook were Schedule H1 drugs. As per DCGI norms, these require recorded sales, red “Rx” labelling, and strict monitoring to prevent misuse and antibiotic resistance. These are medicines with a bright red box on the medicine strip alerting the consumers and sellers that these are serious medicines with serious consequences and have to be strictly controlled.

To test compliance offline, Outlook visited brick-and-mortar pharmacies on the pretext of a “lost prescription.” The response was markedly different. Only Cetirizine was sold without hesitation. Combiflam was sold by one shop, but the strip was cut.

A pharmacist in Kalkaji, New Delhi, showed Outlook the ledgers mandated by the Pharmacy Council of India. These record patient names, prescribing doctors, quantities sold, and dates. The store also maintained an inspection register documenting surprise checks by authorities.

Inspectors even send decoy patients—individuals who plead for restricted medicines without prescriptions. In one ledger reviewed by Outlook, the inspector had written: “Decoy was unsuccessful in buying restricted medicines.”

When the pharmacist learned that Outlook had purchased escitalopram, antibiotics, and painkillers together online, he was incredulous. “For a community pharmacist, that would raise alarm bells immediately,” he said.

However, Bejon Misra finds a flaw in this system as well. “The medicine store you went to, you say the last inspection was some eight years ago according to the ledger. Even brick and mortar stores have little oversight; and we all know if we know the pharmacist he will happily give us whatever we need and put fake names in the records”

Prescription by Perception

Apollo, one of India’s most trusted healthcare brands, enforces strict prescription rules at its physical stores. Online, however, Outlook found a different standard.

Using Apollo 24/7, Outlook ordered escitalopram, azithromycin, and Nucoxia. A call came within a minute. The caller asked for age, allergies, and reasons. The ailments provided were inconsistent and unrelated.

The order was cleared instantly.

The resulting e-prescription was more troubling. It included clinical details, appetite issues, and health complaints that were never discussed during the call—details seemingly added to make the prescription appear legitimate.

The doctor asked the patient name, age, if they were allergic to the medicines being purchased and a few other queries.

It also instructed a daily intake of 650 mg paracetamol for a month, which Dr Roy says is unjustifiable for mild or even severe illnesses. “Dolo for a month? That’s absurd,” says another doctor.

Apollo told Outlook: “The platform follows a multi-step prescription verification and order processing system.”

According to Apollo, uploaded prescriptions are verified by pharmacists, and teleconsultations are meant to cancel inappropriate orders. Outlook’s decoy tests showed these safeguards were not applied.

The doctor showed no care for why a patient was purchasing two batches of painkillers with antidepressants, and quickly wrote an e-prescription to allow the purchase.

Telemedicine Rules Bypassed?

India’s Telemedicine Practice Guidelines, developed with NITI Aayog inputs, clearly state that teleconsultations are not substitutes for full clinical evaluations. Schedule H1 drugs are not meant to be prescribed over calls.

Registered Medical Practitioners may prescribe only after proper assessment. Lists O and A cover low-risk medicines like ORS and paracetamol. The drugs Outlook purchased do not fall under these categories.

Blinkit and Apollo allegedly bypassed these requirements. In many cases, the “consultation” took less time than making the payment.

Antibiotics, AMR, and Silent Damage

On the multiple deliveries of antibiotics within hours, both doctors and chemists expressed concern. The overall sentiment remained the same – self medicating is a cultural issue in India.

Many of us trust chemists and take antibiotics for any fever or ailment on their advice, raising the chances of Antimicrobial Resistance. The National Centre for Disease Control claims AMR is a serious global health challenge where microbes resist treatments, threatening to undo decades of medical progress and making infections harder to treat.

India, in fact, has a ‘National Programme on AMR Containment’. However, online dispensaries are not bound by such constraints. They are driven by instant payment and gratification of returning customers.

A Legal Grey Zone, A Regulatory Failure

India has no law explicitly permitting online medicine sales—and none banning them. Draft e-pharmacy rules introduced in 2018 require registration, prescription verification, pharmacist oversight, and detailed record-keeping. They remain stalled, for what reasons though? Renowned cyber security expert and Supreme Court lawyer Pavan Duggal, says it remains an area that has remained unaddressed by policy makers and therefore a grey zone exploited by the unscrupulous, “The online distribution of medicines is not a priority because it does not belong to a particular vote bank or vote generation. It is also a largely elite activity, one can say, so again it won’t be a poll promise or anything but there needs be an immediate intervention because this is a gross public safety risk.”

Explaining the existing laws, Duggal repeats, platforms exploit the loophole that while there are no laws codified regarding online sales, there isn’t one outlawing it explicitly either.

“IT Act, 2000 is totally silent on the online sales of medicine. The Drugs and cosmetics Act is too old to even have a provision for the same. What is needed right now is one, new legal framework and two, effective enforcement of current and existing laws,” he adds.

“The draft online rules have been in limbo since 2018,” Misra says. “Parliamentarians will have chai and charcha, but it is the people who suffer ultimately.”

Misra is blunt about where the buck stops. “The only person who can stop this is the regulator. What is the Drug Controller General of India (DCGI) doing? What is the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO) doing? How is this happening right under their noses?”

Misra rejects the idea that citizens must complain first. “Why should the government wait for a citizen who may not even know the law or afford a lawsuit? The government must act proactively. And punish these people.”

However, some people have come forward.

A group of chemists is taking online platforms to court. “If we go by the Drug and Cosmetic Act, there was no online when it was written, so that Act has very strict regulations on how to sell medicines. Are these platforms following any of those rules? They pose a serious risk to public safety,” says Jitendra Goel, general secretary of South Delhi Chemist association.

Goel claims the very existence of these platforms is illegal. India’s draft e-pharmacy rules require mandatory registration, prescription verification, pharmacist oversight, 24/7 support, strict data privacy, and detailed record-keeping. Sales of narcotics, psychotropics, and medicine advertising are barred.

The drug act allows sale of medicine only through registered and licensed drug outlets. The processing of online orders and delivery, says the Apollo spokesperson, is carried out by the vast network of Apollo pharmacies across the country.

Patient, Addict, or Consumer?

Apollo insists it follows strict rules. Blinkit offers speed. Both offer access and little accountability. Misra says, “The thing is, no one will come forward with these issues.

A parent wouldn’t come forward if their child is abusing meds because it would shame their parenting, and all those who prefer to buy medicines without prescription, what will they complain about? They would be happy. We are just waiting for a tragedy like the cough syrup incident to happen, for this system to blow up into something uncontrollable”

Until regulation catches up, India’s online medicine economy will continue to operate in this dangerous grey zone. “We need extremely strong regulatory oversight. Do you think people in the US or Europe are more ethical and that’s why pharmacies have such strict audits of medicines? No, they are not. They are simply afraid of the stringent laws that will punish them for dolling out medicines willy nilly,” Misra says, exasperated with the lack of accountability.

Disclaimer: The article reflects findings from Outlook’s investigation and public expert commentary. Companies mentioned have been approached for comment. All claims are based on observed evidence and expert interpretation.