The book brings together three historians who pioneered feminist approaches to Ancient Indian history.

It blends personal journeys with academic insights, revealing how women changed the field’s focus.

Accessible and reflective, it shows how feminist thought made history more inclusive and human-centred.

Women Writing History: Three Generations

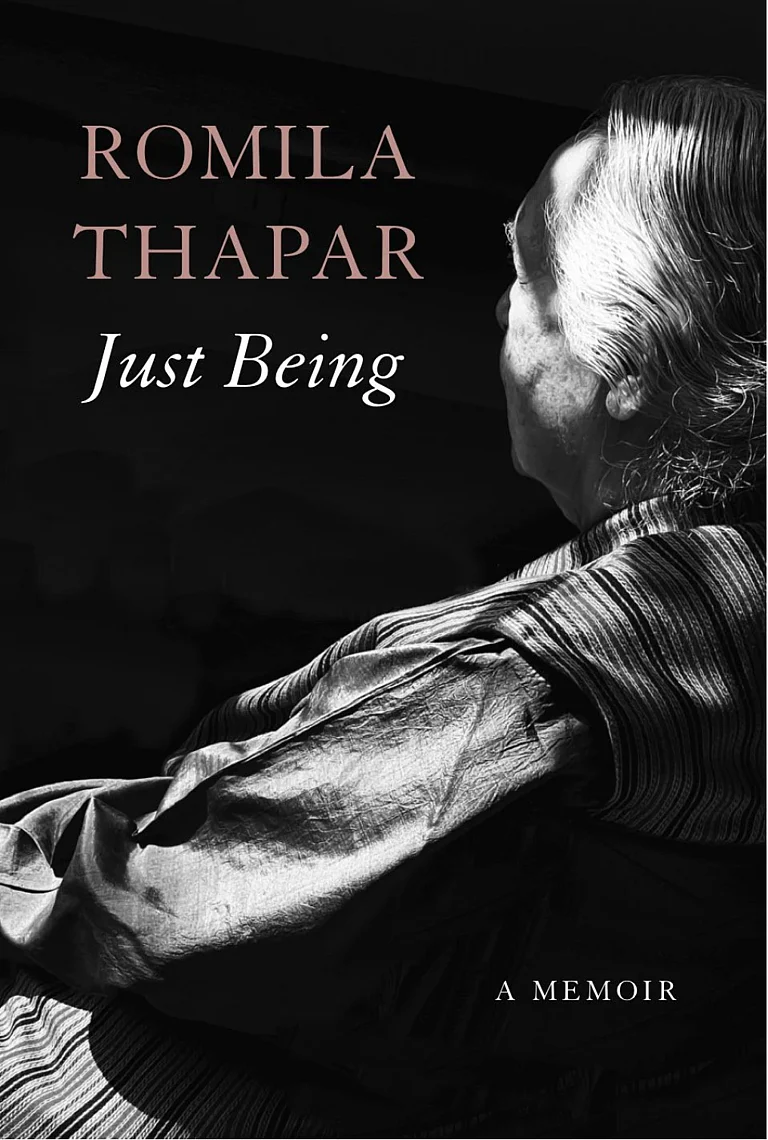

Romila Thapar

Kumkum Roy

Preeti Gulati

Zubaan

INR ₹595.00

Women Writing History: Three Generations brings together the voices of three seminal Indian historians — Romila Thapar, Kumkum Roy, and Preeti Gulati — who reflect in this slim volume on their journeys as scholars and the ways in which feminism has shaped their engagement with history. The book focuses particularly on the field of Ancient Indian History, an area where their contributions have been pioneering.

Romila Thapar, Professor Emerita of Ancient History at Jawaharlal Nehru University, is celebrated for her social-historical approach to early India. She is also noted for her outspokenness in the face of divisive contemporary politics, pointing out how history works by comparing sources and texts to ensure accuracy in the historian’s findings — as in the case of Mahmud of Ghazni’s supposed sack of the Somnatha temple, which appears to have been a non-event as far as the chronicles of the time were concerned.

Such findings set the right-wing trolls on her path, accusing her of being a communist, an “urban Naxal,” or worse. Being a single woman did not help. For someone who calls herself an “Accidental Historian,” she rose to become one of the most serious and respected voices in the field.

Kumkum Roy, also from JNU, has carved a space for gender as a lens in studying ancient history. She begins by writing about growing up in Calcutta in the 1960s, speaking a Bangla dialect with her grandparents, who hailed from Mymensingh. She recalls her school years and Presidency College, where history and English literature vied for importance in her curriculum. She also reflects on her tutors and the struggles that all children face in their formative years, including her own experiences of sexual harassment in Delhi — experiences that made her realise what she had unknowingly faced earlier in Calcutta.

A student of Romila Thapar, she went on to bring together multiple influences to innovate in the teaching of history and to address the very real issues her own students encountered.

Preeti Gulati, currently teaching at Krea University, represents the youngest generation. Her research examines early texts, everyday practices, and institutions, including the role of food and power. Her upbringing and education were markedly different, shaped by a multilingual school environment where Hindi, liberally sprinkled with “cuss words,” became the unifying language.

Her essay, aptly titled Turbulent Times, reflects on her personal approach to history and politics – of the three, she actually took part in protest marches in response to changing political mores. Taught by Kumkum Roy, with access to Romila Thapar’s seminal works, she has carried forward her own distinctive way of engaging with the discipline.

All three specialise in Ancient Indian history, though different aspects, with expertise in Sanskrit textual traditions to enrich the knowledge of history and in unpacking how historical literary traditions in India have been constructed. They all encountered history more or less accidentally, not choosing it as their original discipline but being won over along the way, whether through necessity, fascination or encounters with professors who added new perspectives to their thinking.

What gives the book its differential quality is the way it moves between the personal and the professional in a very interview format from Partition to today. The three historians speak candidly of their experiences as students, teachers, and researchers. They share the challenges of working within a discipline often shaped by rigid frameworks and how feminist perspectives have opened up new questions and possibilities.

Here, feminism is not treated as a single idea but as a set of interventions that have enabled historians to look beyond dynasties and battles, to consider instead everyday life, family, gender roles, and social practices. The lives of the women in the Mahabharata, for instance, emerge as key subjects, or the importance of food in traditional rituals. These reflections show how feminist approaches have made the study of history more inclusive, layered and relevant – though patriarchy may not still agree with it.

Accessible and insightful, Women Writing History is both a record of three remarkable careers and a reminder of how academic disciplines are transformed when women’s voices and feminist ideas are given space. For readers interested in history, feminism, or the intersection of the two, the book offers an engaging and thought-provoking journey across generations