.This is not exploitation, he maintains."We charge a fee for a product, and we get customers." But he acknowledges that the matter is controversial. "We have lots of debates about why we should charge so much more fees for students from poor countries." And in the meantime "we use agents overseas who manage local issues" and bring in students from "our overseas market".

British interests in inviting foreign students are clear: bring in money, build our universities, educate our children, and go back. But there is a comeback to that from what could be a fair number of Indian students.

Like Inder. When Inder switched from Thames Valley University to Katherine & King's, he had joined the little great game being played out between countless Indian students and the British universities—a game of who is going to use who and how. Inder, or that at least is what he gives as his name, was given a visa to come to Britain to study and no more; Inder wants study and more, he wants to stay. "Because basically a pound is a pound and a rupee is a rupee," he says. "And, you know these certificates from these universities, they are no use in India, you cannot get jobs with them. Because in India the standard is too high compared to this."

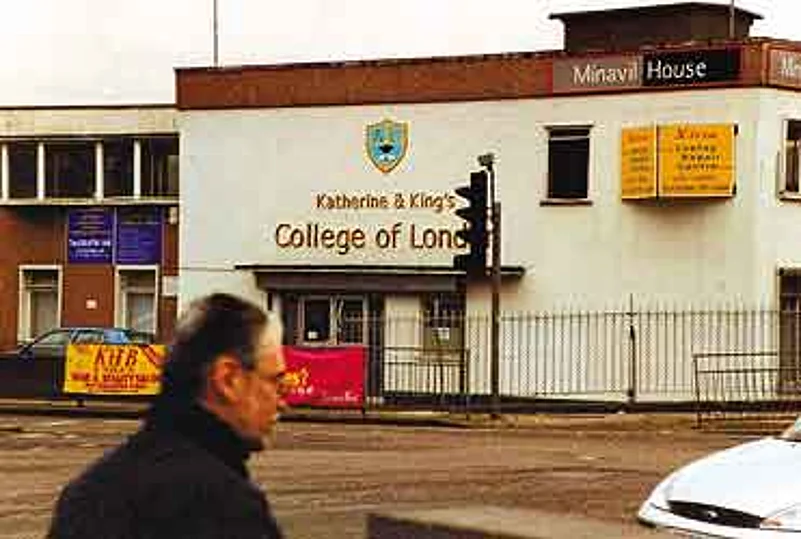

Inder simply moved from a £7,000-a-year course to one Katherine & King's promised at £2,000 a year. That Katherine & King's is a place behind a shutter across from a bus garage in Wembley, and not quite what its brochure seems to suggest, is no problem for Inder. "I'm going to use my savings on the fees and use some more money to buy a car for taxi business," he says. But why didn't he join Katherine & King's in the first place? "I didn't know about it," he says. "Also, for the sake of a visa it is good to join a reputed college first, then shift. You lose first fees which is a big instalment but what to do?"

The heavy fee is "exploitation", he figured after coming here. But British universities calling students like him in their thousands don't think it is. As they see it, the British taxpayer is paying for the British students by way of government grants to universities. But foreign students don't see it that way. As Inder says, "You see how much less students from here pay. They tell us that local students are paid for by taxes, but look at the universities, they get money from us and from the government also."

Every one of dozens of Indian students Outlook spoke to said they plan to stay on in Britain, somehow. "I came here for international exposure," says one student. And he plans to stay exposed. He's really a migrant on a student visa. Like everyone else, he does not want to be named. His determination would be deeply worrying to the immigration officer behind one of those little desks at Heathrow's Terminal 3 if he had any idea who he had just let pass.

Foreign students are allowed 20 hours of work a week, more during Christmas and summer holidays when the British don't want to do anything all. That is useful money, but also a step along the money-making way. "You know, I did some work delivering pizzas for one company in Wembley. The owner is a Pakistani, he came here 15 years back on a student visa, and he is still here on a student visa. We need permission to come here, not to go back."

Indefinite overstay is not the only option. Work can lead to work permits, and that to legal residence. And then there is always marriage. A young girl from Delhi who spent two years in London on a student visa, the second on a just £800-a-year college she never had to attend, married a British Indian last month. Overnight she became 'pukka'.

Whoever wins the little great game in the end, immigrants or immigration control, a sure winner is colleges of the Katherine & King's kind that make ex-polytechnics look like Oxford.

The London College of Business and Accountancy, for example, features a bright picture on its brochure cover of a male student carrying a female piggyback with Tower Bridge behind. Other pictures inside show St Paul's Cathedral and Big Ben. The college has a logo with the look of a knight's shield, except that the wavy ribbon usually drawn below these things does not bear a Latin legend but a bit of a letdown: "Excels in Education & Training."

The college entrance, the entrance to the real college in Wembley that is, lies through a door next to a vegetable shop opposite Wembley Central station. An entrance upstairs is by a hall where Somali refugees gather every day. The pictures in the brochure are quite a change from its actual location in Little Mogadishu. The college has a branchby way of a few rooms in another, and smaller, building, plus a better picture where the whole building could be mistaken for the college. But it's a safe disconnect. You can't see the college unless you have admission. If the college can get a student here, he won't complain because after all, he's here. The cheapest course in this college owned by a Pakistani is at £2,000. A man at the college said the fee "is not negotiable but you can talk to the principal".

Little new colleges are coming up all over London now, dedicated more to earning than learning. The colleges issue letters of admission over the internet for a fee. Those letters can become a basis for a student visa application. Or, they are around to welcome students of the Inder kind; get the visa off a university even if it's an ex-polytechnic, and then transfer to one of these cheaper ones. There don't seem to be many students landing up here whose thirst for knowledge is greater than their hunger for money.

There is more learning on offer in the ex-polytechnics, even if educating one Indian here means educating also a few unknown Brits. If after all this British students still don't manage to get educated enough, no one can say that Indian students did not do more for them in ways their own parents could not.