On the occasion of Shiv Jayanti on February 19, 2024, days ahead of the implementation of the Model Code of Conduct (MCC) for the 2024 Lok Sabha elections, residents of the laidback village of Sao Jose de Areal in south Goa woke up to the sound of JCBs and a huge commotion. A life-size statue of Maratha warrior Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj was being installed on a low hill in the remote village located in Salcete taluka, about 40 km from the capital Panjim and just 7 km northwest of Margaon. The villagers claim that the statue was installed by “outsiders” without permission from the Gram Panchayat. The situation escalated after Goa’s social welfare minister Subhash Phal Desai, Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) sitting MLA from Sanguem, arrived on the scene to allegedly “get the situation under control”.

Panchayat member Joycee Dias and other residents of San Jose de Areal claim that the minister and other senior government officials came to inaugurate the statue and that objecting locals were lathi-charged by the police. FIRs have been filed against at least 20 villagers including Panchayat members like Dias.

“We were not against Shivaji or the construction of his statue, but only against illegal construction. These are tribal areas and any construction must be done with the permission of local authorities,” Dias says. Villagers suspect the incident was an attempted “land grab”. They point out that the land is privately owned by a Muslim man who lives in Margao and wasn’t present at the scene when the construction happened. “This is a Christian village. What message are they trying to send by putting up a Shivaji statue forcefully?” resident Julio Fernandez wonders.

The incident, which became a flashpoint of polarisation in the lush, Catholic-majority villages of south Goa ahead of the fourth phase of the Lok Sabha elections on May 7, highlights a new strand of identity politics taking shape in Goa.

Shivaji has always been an influential figure in states like Maharashtra and Goa, and “Maharashtrawaad” is not new to Goa’s contemporary politics. But religious majoritarianism, which is currently prevalent across many other parts of India, seems to be changing the Goan landscape and its famous “susegad” (relaxed) mentality.

In February 2017, so-called “Hindu groups” tried to erect a statue of Shivaji at the centre of a traffic square in Hathwada, a Muslim-majority neighbourhood of Valpoi, which already had an old statue of Shivaji located inside a garden. Upon the installation of the new statue in Hathwada, locals including Hindu, Muslim and Catholic residents of the area decided to officially renovate the old statue in the Valpoi Garden. Following the renovation of the statue in the garden, the one installed overnight in Hathwada by unknown individuals was removed. In 2018, however, on the occasion of Shiv Jayanti, self-proclaimed “Shiv premis” came forward again and objected to the removal of the Hathwada statue. The group of Shiv premis was backed by the Shiv Sena’s local unit which filed a “complaint of theft”.

In 2020, a life-size statue of Shivaji was installed at Hutatma Chowk in Mapusa, after obtaining permission and a resolution of the Mapusa municipal council. On June 4, 2023, the Shivswarajya group installed a statue of Shivaji in Chogm Circle near the Calangute police station. After the local panchayat ordered the removal of the illegal construction, a crowd of Shiv premis gathered outside the panchayat office and gheraoed it, forcing the panchayat to roll back its order and apologise.

A similar incident happened in August 2023 when Father Bolmax Pereira, a Catholic priest, was booked for allegedly hurting religious sentiments after he made a statement about Shivaji during a sermon in which he said, “We have to have a dialogue with our Hindu brethren and ask them ‘Is Shivaji your god? Or a national hero’? If he is a national hero, leave it at that. Don’t make him a god. We need to understand their perspective. If we live in fear, we will not be able to rise again.” The priest later had to apologise after mobs called for his arrest.

While the issue appears non-political, BJP leaders have been found to endorse these constructions and even Opposition leaders have not failed to milk the issue. Majorda-based lawyer and activist Radharao Grascias says that the Shivaji iconography allows some Hindu groups to target two marks with one arrow. “The Marathas fought both Christians and Muslims.”

Shivaji in Goa

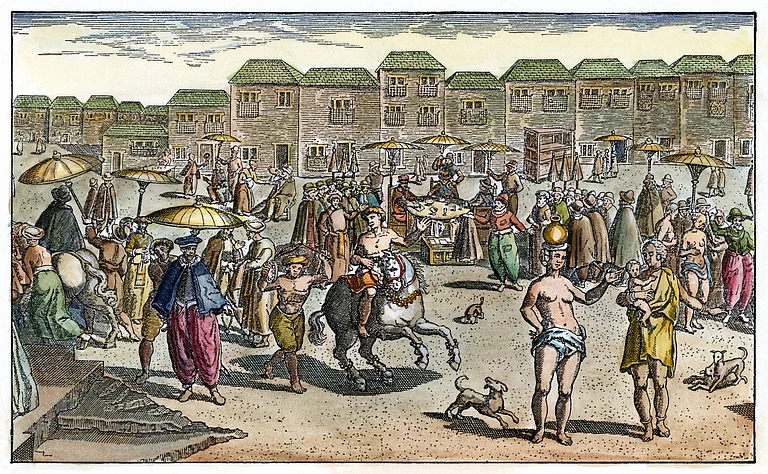

The narrative of Shivaji, though not directly communal, has religious undertones. Shivaji is said to have ordered the construction of the Saptakoteshwar Temple devoted to Shiva in Narve district of north Goa, about three centuries ago. The temple was renovated in 2018 and CM Sawant attended its inauguration. While the actual arrival of Shivaji in Goa remains a contested fact among historians, his son Shamabhaji did come to the state and in 1683, he undertook a nearly successful campaign to defeat the Portuguese and “liberate” persecuted Hindus.

Centuries later, Shivaji’s history remains a ready-to-use pitch in the hands of politicians. Last year, at the 350th anniversary of Shivaji’s coronation at Betul Fort, Sawant stressed that the Portuguese had destroyed temples in Goa and that it was time to “wipe out symbols of Portuguese rule and have a fresh start”. In his 2022 Budget speech, Goa CM Pramod Sawant said that the Portuguese systematically destroyed Goan culture. Later in August, at an ‘Amrit Ka Mahotsav’ event, he accused the Portuguese of looting Goa’s rich natural reserves.

The pulse of the “reclaiming lost temples” narrative dates back to the 16th-17th centuries when persecuted Hindus from Old Conquest areas like Salcete, Bardez and Tiswadi (Panjim region) carried the idols of their deities with them on wooden boats across the Mandavi and Zuari rivers that met at the kingdom of Ponda, which was ruled by a Hindu king at the time. Having found shelter, the families set up the idols across Ponda and built new temples painted in bright colours. They dot the landscape of Ponda taluka to this date.

Artist Subodh Kerkar, who runs a studio in Bardez, stresses that it is important to note the multiple histories of Goa and not just the single one that suits political narratives. Said to be a centre of Buddhism in the 3rd century BCE during the reign of King Ashoka, Goa became a Hindu kingdom following the 4th-5th centuries BCE with various Hindu dynasties, including the Bhojas, the Shilaharas, and the Kadambas ruling over it. In 1498, Goa came under the control of the Adil Shahi Sultanate of Bijapur, which was a part of the larger Deccan Sultanate. The Adil Shahi dynasty ruled over Goa until the early 16th century, when Portuguese explorers arrived in the region and eventually established colonial control.

“What Goa is today is an amalgamation of these many histories and the Goan identity cannot be understood by secluding one history from the other,” Kerkar says. His studio, titled “Museum of Goa” houses aspects of all the histories—documented and unrecorded—that make up Goa. His centrepiece upon entry is a larger-than-life boat titled ‘‘Goa’s Ark’’ depicting the passage of gods and goddesses across the rivers Zuari and Mhadei to Ponda. “This is definitely a part of Goa’s history and history should be learned and understood. But it should not be used to antagonise those living in the present,” Kerkar cautions.

The ‘‘temple taluka’’ of Ponda has nevertheless remained a centre of religious polarisation and right-wing activities with right-wing outfits like the Sanatan Sanstha headquartered here. The outfit, which has been controversial due to allegations of involvement in criminal activities and

extremist ideologies, was recently in the news again after a Pune court convicted two people linked to the organisation in the murder case of anti-superstition activist Narendra Dabholkar. They received life imprisonment for the murder, which took place in Pune on August 20, 2013. Members of the group have also been linked to the murders of other rationalists and activists like academic M M Kalburgi, CPI member Govind Pansare and journalist Gauri Lankesh.

Writer, activist and Konkani academic Damodar Mauzo, who has previously received death threats from the Sanatan Sanstha, said that despite attempts to sow seeds of communal hate in Goa, groups like the Sanstha have so far been unable to damage Goa’s social fabric.

Having set up its ashram at Ramnathi area of Ponda in 1999, the Sanatan Sanstha lost its credibility among Goans after 2009 when the group was accused of trying to orchestrate a blast in Margaon during the annual Narkasura slaying festival on the eve of Diwali in Goa which left two people dead. “After investigation, it appeared at the time that members of the Sanstha had planned blasts across Goa and were trying to make it look like the Muslims were behind it. The incident led to a loss of confidence among Goans regarding the intentions of the Sanstha,” Prashant Naik, ex-president of Konkani Bhasha Mandal and current head of the Nirakar Education Society, recalls.

“Goa is known for its exemplary harmony. We are good neighbours. I live in Majorca where the majority are Christians. But I never felt they were the ‘other’, nor did I feel like the ‘other,”’ Mauzo says. "It’s because most of the Catholics in Goa were also at some point Hindus. Many Christian communities retain some of their original Hindu customs and many Hindu communities have adapted to Catholic traditions or virtues.” The Jnanpith awardee nevertheless admits that over the years, especially in the last decade, “fanaticism has entered Goan society”. “There has been an increase in religiosity across all religions, which is not bad in itself,” he says.

“But it should not mean projecting one religion as superior to another. That kind of hatred seems to have entered our society and I am more concerned about that,” he adds.

Fluxing identity

With Goa’s “Hindu identity” getting louder, marked by a distinct rise in saffron flags depicting Ram, Hanuman, and Shivaji festooned across many neighbourhoods and villages, both the minority (and fast-shrinking) Catholic population and the even smaller percentage of Muslims in Goa have felt the heat. While it is a misconception that Goa is a Christian majority state, Catholics do form a large minority population in Goa, making up about 25 per cent of the population as per the 2011 census. Radharao Gracias notes that the Catholic population has decreased a lot since then and especially after the BJP came to power in 2014. An increasing number of Catholic Goans have been opting to register as Portuguese citizens. Portugal allows those born in Goa before December 19, 1961—the day Goa was liberated from Portuguese rule—and two future generations the option to get Portuguese passports. By doing so, they lose the right to vote in India.

“Since the BJP has gained strength in the state and at the centre, the Catholic population has been feeling restless. It’s not fear of religious persecution per se. Christians have a hard time getting government jobs,” Gracias alleges.

Employment has also become a concern for Muslims who form 8.33 percent of the population (Census 2011). Saiyyad Majid, who used to run a battery shop in Vasco where he lives has been jobless for months after his shop ran into losses following the implementation of GST. “Earlier, uneducated people could get employed in technical lines or open small businesses. The GST laws have had a big impact on the Muslim population here, much of which relied on the small and medium businesses,” Mushtaq Ahmed, whose family owned the first bakery in Vasco, adds that in older times, the divide between religious groups used to be less. “I remember sharing meals with my Hindu and Christian friends on Diwali, Christmas and Eid. That level of bonding is missing now,” says Ahmed, who lives abroad with his family.

Referring to incidents like a Hindu deity being planted by miscreants in the vicinity of the church in Sancoal, Salcete, Mauzo points out, “Hate-provoking speeches and activities have been going on across Goa.” While blaming the politics of identity, Mauzo also places the onus on “outsiders” for the changes in Goa.

“I straightway blame the “outsiders”—people from other states, who have made an influx into Goa. These are the people bringing in their own polarised religious identities and triggering existing chasms while creating new ones among the original communities living in Goa,” Mauzo says. He adds that the rise in the number Shivaji statues is nevertheless disconcerting, especially since most of them are being built without legal authorisation from local authorities.

“It points toward a dangerous new trend of iconoclasm,” the author warns.