Hungarian writer Laszlo Krasznahorkai has been awarded the 2025 Nobel Prize in Literature

Critics have hailed Krasznahorkai as ‘the angry prophet of the apocalypse'

The Nobel Laureate grew up in Soviet-era Hungary in the 60s and late 70s

“...All normal expectations went by the board and one’s daily habits were disrupted by a sense of ever-spreading all-consuming chaos which rendered the future unpredictable, the past unrecallable and ordinary life so haphazard that people simply assumed that whatever could be imagined might come to pass, that if there were only one door in a building it would no longer open, that wheat would grow head downwards into the earth not out of it, and that, since once could only note the symptoms of disintegration, the reasons for it remaining unfathomable and inconceivable, there was nothing anyone could do except to get a tenacious grip on anything that was still tangible…”

― László Krasznahorkai, The Melancholy of Resistance

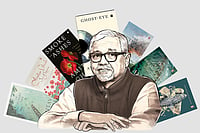

When asked to respond to being awarded the 2025 Nobel Prize in Literature, Hungarian writer László Krasznahorkai’s first reaction was to channel Samuel Beckett—the avant-garde Irish writer who received the Nobel in 1969. “What a catastrophe!’ Beckett had remarked when he heard about his win,” Krasznahorkai (71) chuckled, before going on to share that he is proud and happy to be honoured with the Nobel, which connects him to a stellar line of writers, and gives him the power to continue to write in his own language (Hungarian). The new Laureate’s kinship with Beckett is not hard to fathom. Krasznahorkai too writes about a fractured world, broken systems, the desolation of humans living through it all. His fiction is strange, shocking, funny, frightening, beautiful—capturing the many contradictions of life in our particular cultural and political moment. There is decay and breakdown, collapse and chaos; there is also a glimmer of humour in the dark. Krasznahorkai’s novels unravel in the backdrop of central European towns and villages and bleak landscapes. Influenced by his travels in China and Japan, he has also crafted narratives that are set in the Far East.

Critics have christened Krasznahorkai ‘the master of absurdist excess’ and ‘the angry prophet of the apocalypse’. He himself once described his work as an endeavour to examine reality ‘to the point of madness’. On October 9, the Swedish Academy announced that he was being recognised “for his compelling and visionary oeuvre that, in the midst of apocalyptic terror, reaffirms the power of art”. Anders Olsson, Chair of the Nobel Committee, hailed him as a “great epic writer in the Central European tradition that extends through Kafka to Thomas Bernhard, and is characterised by absurdism and grotesque excess.”

Born in Gyula, a small town in Hungary during the Soviet era, Krasznahorkai was fascinated by music. As a young boy, he played in jazz bands and rock groups and was a professional musician for a few years. No surprise then that in his writing, he is acutely aware of the rhythm and melody of sentences. “He is a hypnotic writer,” well-known poet George Szirtes, who translated Krasznahorkai’s debut novel Satantango into English, told AFP. “He draws you in until the world he conjures echoes and echoes inside you, until it’s your own vision of order and chaos”.

Reams have been written about Krasznahorkai’s style: his penchant for long sentences, his obliviousness to full-stops, his paragraphs that flow on without breaks. In an interview with The Paris Review, Krasznahorkai said that his style was not a conscious choice. “If you want to say something very important,” he explained. “You don’t need full-stops or periods but breaths and rhythm—rhythm and tempo and melody…This kind of rhythm, melody, and sentence structure came rather from the wish to convince another person.”

Growing up in Soviet-era Hungary in the 60s and late 70s, Krasznahorkai didn’t have dreams of becoming a fulltime writer. He was an avid reader. Kafka was a literary hero; The Castle his personal favourite. He also read and re-read Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano. When he began to write, his ambition was simple: write one book. He moved around a lot to avoid being recruited into mandatory military service; travelled from village to village, town to small town; working small jobs (miner, nightwatchman of cows, director of culture houses in villages) and writing his first novel. Artists were under surveillance then. There were strict rules about what could be written, what could be said. Even though he wasn’t a big name in literary circles, he was summoned by the police. There was intimidation, veiled and not-so veiled threats to reckon with.

His first novel Satantango, which turned him into a literary sensation, was published in 1985. It was later adapted into a seven-hour film by Béla Tarr. Krasznahorkai is the author of five novels, including The Melancholy of Resistance (1989), War and War (1999) and Herscht 07769 (2021). He has been awarded several literary prizes, including the 2015 Man Booker International Prize. His translators— Szirtes, Ottilie Mulzet and John Batki—who brought his prose to the Anglophone world deserve special thanks. Without them, his challenging and complex works, written in Hungarian, would not have sailed across linguistic borders.

Speaking to Swedish Radio in the wake of the Nobel announcement, Krasznahorkai said that he had started off with the plan of writing just one book. It so happened that after reading his first novel, he felt the urge to do better by writing another. And so it went on… “My life is a permanent correction,” Krasznahorkai said, leaving readers with the hope that his remarkable oeuvre will continue to grow.