The Elsewhereans blends personal history with fiction across generations.

Set in Kerala and beyond, it explores love, memory, and exile.

The story circles back to a family home by the Muvattupuzha River.

One night in late November I cross the under-repair bridge on a nameless river—might be an ingress of the Arabian Sea—inhaling hyacinth-layered dark water on my way to Poornathrayeesa Temple to breathe in the verve of the annual festival. Seven caparisoned elephants in a row mildly swing their trunks to the tune of the large resonant bell and beats of the chenda drum. Burnt ghee from the glowing diyas hangs thick in the air around. In an upstairs hall, lavishly painted Kathakali performers are waiting for the classical singer to end his recital. The god here definitely has a baroque grandeur, a flair for extravagance. And as if to lend colour to the deity’s majesty, well-turned-out boys and girls look for lonely corners to get lost in closer moments.

In Kerala, you are indeed never further from God, love and rivers wherever you go. This truth keeps coming as a refrain as you turn the pages of The Elsewhereans—Jeet Thayil’s deeply engaging family saga. Being faithful to the characters inhabiting the narrative, he has preferred to call his latest work a documentary novel. Impervious to semantics, The Elsewhereans still makes an important point: the best fiction always comes out of the author’s life.

Well, first love. A journalist from Bombay—not yet Mumbai—flies down to Cochin to reach a school—not very far from the temple I visited, I guess—to meet the young teacher he is going to marry, an old picture from her school days in his wallet. He looks at Ammu: “The simple cotton sari with a red border, the string of jasmines in her flyaway hair, the shy smile and clever eyes.” This is the age of innocence and idealism for the young man in love and also for India at the crossover of colonialism and democracy.

The tharavadu, with its storied history, myths and fables, matches the exuberance of the Muvattupuzha flowing by its edge in all its eccentricity. The river is like destiny, guiding the lives of those for whom the deeply wooded family home is the first identity mark.

In this extraordinary setting, God too reveals Themselves in a bit of an idiosyncrasy. “I’m (more) Hindu than Christian,’ George declares…I prefer not to have the ceremony in a church.’’ With George taking his bride to Bombay to set up home, the trail begins for two peripatetic generations anchoring around half the world to do bit roles and see what games life plays with them.

There is a ruggedness about the novel that seems intended. Thayil has set out not to write smooth fiction in easy, comforting prose. Rather, he seeks to reinvent his personal history as fiction, knowing the severe limitations the job puts him in. Every corner of the field—foreign or native, known and unknown—that the family members have explored across generations, is both a standalone story and equally enhances the Gothic structure of the narrative, too. You take away one chapter, one locale, and the story still stands, but a lot more bereft, without the majestic sweep of the whole.

Of all the places the nowhere man sets sail to, my favourite—of course after the family seat on the river—is Vietnam. Today Vietnam for the Indian middle-class is ‘affordable foreign’. But for me, growing up in the deep red of suburban Calcutta—never Kolkata—it was a land of indomitable courage and unrelenting resistance.

I was fired up by the retelling of the Battle of Điê . n Biên Phuù and saw in my father’s library Bertrand Russell’s War Crimes in Vietnam. An artist of the CPI group pinned up on a board in the town square, his gripping red-and-black watercolour depicting the essence of the gutsy land’s swashbuckling fight against American imperialism.

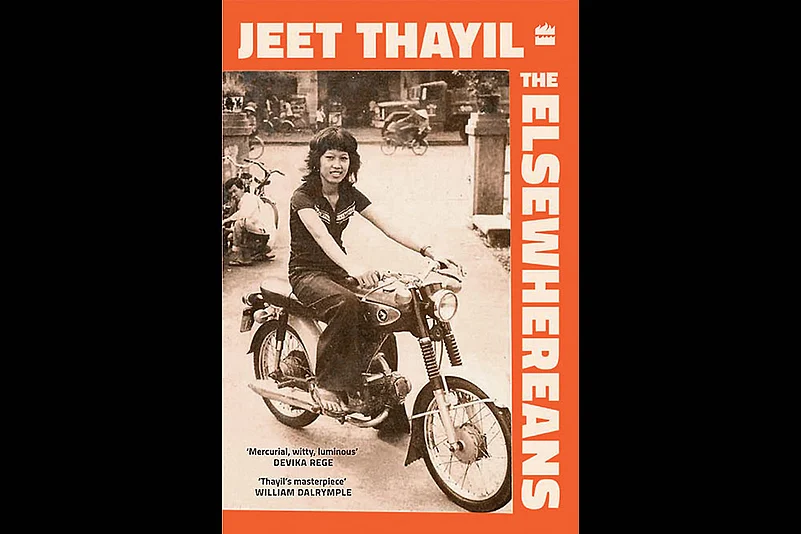

Vietnam was all about suffering, brilliant guerrilla warfare and an estimated three million deaths. I never thought that M., a spunky young woman riding a motorbike, could be part of that desolate landscape. Ammu is the pivot things revolve around. But M., coordinating with foreign correspondents covering the war, is what makes the story a story—the allure, guts, commitment to the cause, and guilt, too.

The narrative’s circular structure—the trek ends at the musty old house it started from—evokes the river mystique. The Muvattupuzha recalls the children who went out into the big bad world. Unlike us, the river forgets none. “…he will carry to the house where she, and he, were born, twenty-five years apart, to immerse her in the river that begins this story…”

The article appeared in the Outlook Magazine's October 1, 2025, issue Nepal GenZ Sets Boundaries as 'Home And The World'