Summary of this article

Olive Nwosu's Lady follows a female taxi driver coursing through night-time Lagos.

The film won the World Cinema Dramatic Special Jury Award for Acting Ensemble.

Lady is next headed for its European premiere at the Berlin Film Festival in the Panorama strand.

Playing the titular protagonist in Olive Nwosu’s Lady, Jessica Gabriel’s Ujah summons such severity it blinds and expels anyone who dares to mess with her. It’s the kind of performance that can confidently hold a film in place irrespective of flaky writing. In a fairer world, this star-making turn would line up a bevy of directors eager to cast her. But as her own character brashly hints, she couldn’t be less bothered.

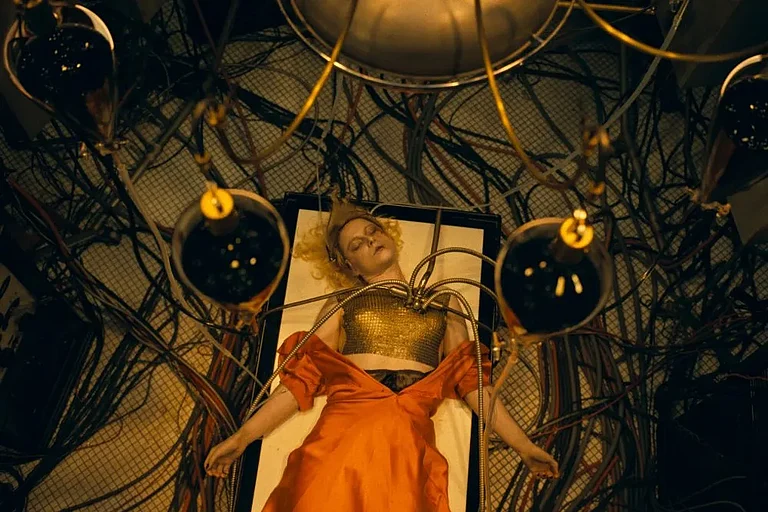

Premiering at Sundance, Lady explodes with stabbing visual energy as it cruises through Lagos. As a female cab driver, Lady knows she’s an anomaly. But she’s vehement in not letting it define or limit her in any way. She wields a brittle, unbreakable front that warns bullies to keep a safe distance. She keeps her femininity at bay. When an old friend Pinky (a powerful, passionate Amanda Oruh) accosts her, Lady is uneasy. The job is to drive around Pinky and her fellow sex workers at night. After some needling, especially considering it’s well-paying, Lady takes up the offer.

Within the provocation of these vivacious women colliding with someone as aloof as Lady, Nwosu finds something incredibly light. She holds up glinting shards and endears us to her plucky characters who hinge on each other and endure overwhelming situations. Lady ferociously protects her independence. She’s been through a lot and earned the place where she’s reached. She prizes nothing else as much. Ujah laces her with a tight, unswerving sense of dignity. Lady can come across as too guarded, flinching at demonstrativeness. But she’s fuelled by a deep rage, an immovable instinct for self-preservation. She knows danger acutely and draws up borders quickly. This is a character that could have tipped into a certain coldness. But Ujah situates the impermeability along with an ache for more. When by herself at home, she’s giddy about her dreams, ecstatic more money is pouring in. Lady’s dreams aren’t outrageously far-fetched. All she wants is getting to Freetown in Sierra Leone, her mother’s birthplace. She saves up with that ambition in mind.

Her desire amuses the band of women. Surely, as they suggest, one dreams of stuff like going abroad, not reverting to yet another godforsaken place in their doomed country. The streets are burning. The government is slashing fuel subsidies, unemployment surges and so does inflation, rendering everyday living almost impossible. Initially, Lady chafes at the chauffeur proposition. She can barely hide her being scandalized, her absolute distaste for the profession. Wisely, Nwosu doesn’t flatten the sex workers into a homogenous prototype. They do have differences regarding their work, how they perceive it. But that doesn’t come in the way of respecting each other. One claims none of them would voluntarily continue as a sex worker if there was an alternative. Another rebuts that this is better than being someone’s hapless wife. Lady’s journey is also about expanding her sensitivity. She becomes more inclusive and learns to laugh a bit.

Nwosu’s screenplay does suffer a beating in stretches. The film braids in the Nigerian revolution bursting through the streets to half-formed effect. Disaffection courses through the public that has had enough. A radical DJ, whose voice on the radio comes as a wake-up call, informs the narrative’s political landscape. Lady dips in and out of the larger scale, whilst being most invested in the women’s joys and trials. Nwosu could have interspersed few more daytime scenes, adding a vivid public space Lady otherwise navigates without the women.

Thankfully, Nwosu assembles a rip-roaring, richly authentic ensemble of actors, just being in whose company is as delightful as disarming. They suffuse Lady with vim and zest, propping a portrait of womanhood frequently contradictory and always rousing. Ujah injects Lady with a firmly vigilant eye. She’s constantly alert. It’s the women who teach her to loosen up. At night, they are glorious, certain how to draw the most out of it. The electrifying cast lend specific dimension to character sketches that are otherwise too broad. Despite the first-time actors’ full-bodied conviction, their characters come off as replaceable. Apart from Pinky, you don’t get a sense of how far they’ve travelled, how they look forward. Peeks into Lady’s past, trauma that stoked her sexual unreceptiveness, are registered as a startling fugue by Alana Mejia Gonzales’ camera, but they remain vague. Lady is striking in bits and fits, but does muster a satisfyingly defiant finale, as the personal and political bleed together.

Debanjan Dhar is covering the Sundance Film Festival as part of the accredited press.