Summary of this article

One of the consequences of the Inquisition was the systematic suppression of Hindu practices among converted Catholics.

Inquisitorial mandates prohibited attendance at Hindu temples.

It is estimated that over 16000 trials and persecutions took place during the inquisition.

Goa became a Portuguese colony in 1510 and remained so until its liberation in December 1961. Whatever happened in Portugal in that period impacted Goa directly, but few know that there was also a Goa inquisition that lasted almost 250 years and claimed several Goanese lives.

Inquisition was a system of judicial investigations and courts run by the catholic church from the 12th to 17th centuries, mostly in Southern Europe to identify, judge and punish people accused of heresy. Inquisitions continued for nearly 700 years and led to more than 12000 people being killed, including by burning them alive. Inquisitions such as the Spanish and Portuguese operated directly under royal authority and focused heavily on converted Jews and Muslims. The inquisition tribunals used formalised procedures—interrogation, witness testimony and at times torture—to enforce Catholic doctrinal conformity. The Portuguese Inquisition, established in 1536 basically targeted “New Christians” who were descendants of Jews forcibly converted in 1497, and suspected of secretly practicing Judaism. In many cases, the inquisition also policed sexual morality, superstition and Protestant influences during the Reformation.

By the mid-16th century, Goa had a diverse population of Hindus, Muslims, Jews and those that had converted to Christianity under colonial rule. In order to ensure conformity to Catholicism from the newly converted, the Goa Inquisition was established in 1560 and continued till its formal abolition in 1812. It was set up as authorities suspected that many converts retained ancestral rituals, which the Church considered idolatry or apostasy. In addition, the inquisition also served as a political tool that helped consolidate Portuguese colonial authority by enforcing Catholic norms, regulating cultural practices and suppressing resistance masked as religious difference.

The history of Portuguese influence in India can be traced right back to the arrival of Vasco da Gama to India in 1498, whose task was not only to find a sea route to India, but also spread the Christian faith in India. In Goa, it owes its origins from the arrival of the Portuguese in 1510 under Afonso de Albuquerque, who envisioned the region not merely as a trading post but as a Christian bastion in the East. Over subsequent decades, missionaries – especially the Jesuits – pushed for increased oversight of religious life in the colony. The inquisition was the answer and the tribunal was staffed by inquisitors sent from Portugal, supported by local clergy, and backed by the extensive Church-state partnership as was prevalent in Portugal.

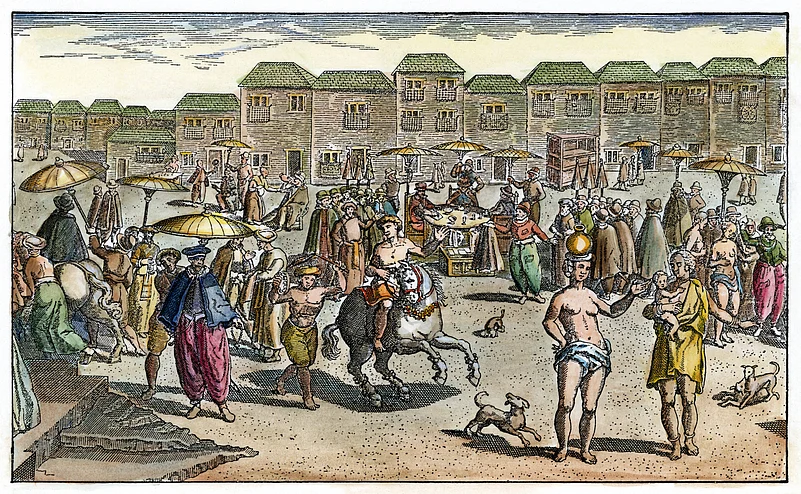

One of the most significant consequences of the Goa Inquisition was the systematic suppression of Hindu practices among newly converted Catholics. Inquisitorial mandates prohibited attendance at Hindu temples, wearing of the tilak or performing rituals, celebrating Hindu festivals, using traditional names, maintaining ancestral idols at home etc. The cultural restrictions extended beyond religion. Social customs such as marriage rites, mourning practices, or dietary rules became grounds for prosecution, if interpreted as “heretical persistence”. Beyond the majority Hindus and converts, the Inquisition also affected Muslims, Jews, and even Christians accused of heterodoxy. The tribunal’s reach extended into literary and intellectual life as well, banning texts, policing ideas, and restricting contact with non-Catholic traditions. The Goa Inquisition served political ends by reinforcing Portuguese colonial control by monitoring local elites, merchants, and even members of the Church who opposed official policies.

Resistance to the Inquisition took various forms. Some Goans fled to territories under Indian rulers, such as those controlled by the Marathas, creating communities beyond Portuguese reach. Others negotiated limited exemptions or found ways to maintain traditions clandestinely. The inquisition targeted not only locals but even foreigners.

Some prominent victims of the Goa inquisition include the French physician and traveler Charles Dellon (1649-1710), who was not a Goan. He was arrested in Daman, transported to Goa, interrogated, tortured, and imprisoned for five years on charges of criticizing Catholic rituals, possessing forbidden books and “irreverence” toward religious authorities. After his release, he wrote Relation de l’Inquisition de Goa (1687), one of the most valuable primary sources describing the inner workings of the tribunal. Local Goans included Domingos Paes and Antonio Paes, brothers from a notable family who were converted Catholics. They were charged with secretly practicing Hindu rites and maintaining old customs. Their property was confiscated, and they were imprisoned. The Paes family case is often cited to highlight how the Inquisition targeted elite families to enforce conformity. Another wealthy landowner named Fransisco Felix faced similar charges. His case appears in inquisitorial summaries preserved in Lisbon; he was tried, publicly humiliated, forced to perform penance and had his property confiscated.

Several well-known local leaders were also targeted by the inquisition, including local village heads (Gaonkars), who converted to Christianity but retained their rituals. They were tried for visiting Hindu temples, sponsoring festivals, consulting astrologers and performing traditional marriage or mourning rites. Similarly several Muslim converts were also tried. Even Christian priests of Goan origin became victims of suspicion when they retained local customs or resisted Portuguese control. Many were accused of Introducing “Hindu superstitions” into Catholic rituals, unauthorized teaching and challenging the authority of European clergy. Even Goan sculptors and craftsmen, who traditionally carved Hindu images, were arrested for continuing their trade after conversion.

The case of the Cuncolim Martyrs (1583) is another well known example. It is the first case of armed resistance against Portuguese rule in Goa. Much like the revolt of 1857, it was also triggered by tensions over religious interference, temple destruction and attempts at forced Christianization. A group of 5 Jesuit missionaries who went to Cuncolim to preach, were killed by the local villagers. The Portuguese colonial government responded by inviting 16 village leaders to negotiate but instead captured them and executed 12 of them. Four escaped. The village was placed under military occupation and lands of the leaders were seized. People were forced to convert, places of worship were destroyed and entire clans were punished or displaced. The action was taken by the Colonial government with elements of inquisitorial authority.

A particularly gory and famous case was that of a Portuguese lady named Catarina de Orta, who had converted from Judaism to Christianity. She was arrested by the Inquisition in Goa on 26 October 1568 and accused of secretly practicing Jewish rites. Her trial is one of the few whose records survived and sheds light on the workings of the Goa inquisitions. Her brother was the prominent physician and scholar Garcia de Orta who went from Portugal to Goa in 1538 and lived there till his death in 1568. Panjim still hosts the ‘”Garcia de Orta’ municipal garden that was built in 1855 and is named after him. Her sentence was pronounced on 25 October 1569 and was burnt alive on the stake. Subsequently even Garcia de Orta’s remains were exhumed by the inquisition and burnt with his effigy in 1580.

The records of the Goa Inquisition were destroyed or never kept, but it is estimated that it was responsible for over 16000 trials and persecutions. The inquisition was conducted without public transparency and many documents were destroyed upon its abolition, leaving historians to reconstruct details from surviving files in Lisbon, Rome and Goa. The number of formal documented executions of the Goa Inquisition is 57 persons who were burnt alive, including 16 women. The number of people subjected to prison, torture or other punishments is not known, but regardless of the statistics, the institution’s reputation for severity is well-documented. While its precise dimensions remain debated, the institution undeniably shaped the cultural landscape of Goa and remains a powerful symbol of the tensions and the power dynamics between the colonizer and the colonized in that period.

The author is India’s Ambassador to Portugal.

Views expressed are personal