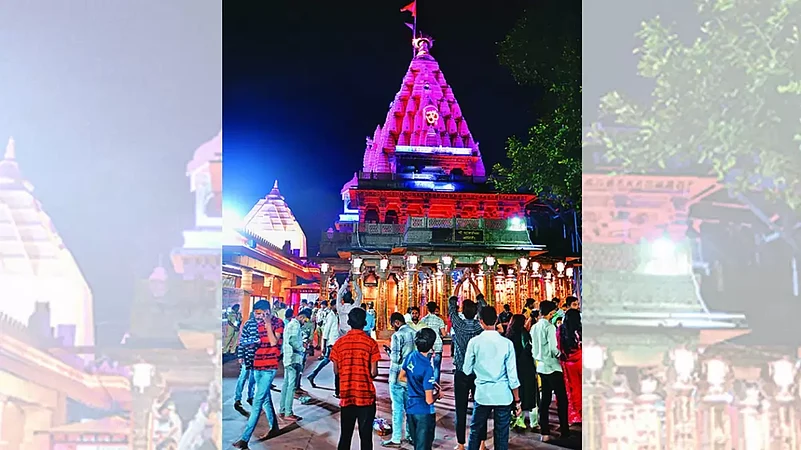

Devotees at the Mahakaleshwar temple are greeted with a Sanskrit sloka, “It is rare for humans to be born in Bharat and even rarer is the opportunity to worship Shiva.” For many, the temple and the town in which it is located—Ujjain, about 200 kms west of Bhopal, the capital of Madhya Pradesh—is synonymous not only with spiritual emancipation but also with India’s ancient history.

This sentiment was given a boost on October 11 when Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurated the first phase of the Mahakal Maharaj Mandir Parisar Vistar Yojana—a plan for the expansion, beautification and decongestion of the Mahakaleshwar Temple and its neighbourhood. While the estimated cost of the first phase is Rs 350 crore, the entire project is pegged at Rs 856 crore.

Interestingly, this comes ahead of the upcoming Karnataka elections where the Lingayats, a Hindu Shaivite community comprising almost 17 per cent of the state population, play a significant role. Known as the followers of Basavanna, the 12th-century social reformer who fought to eradicate inequality, the Lingayats play a decisive role in 90–100 seats out of the 224 assembly constituencies.

Since the resignation of the Lingayat strongman, B.S. Yediyurappa, last year, all is not going well for the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in terms of its Lingayat connection. More than 100 Lingayat mutts showed their support for the former chief minister and warned the BJP of an unexpected fallout, even as two seers of the powerful Lingayat mutts, Basavajaya Mrityunjaya Swami and Dingaleshwara Swami, came out against Chief Minister Basavaraj Bommai, over graft and reservation issues.

A controversy over the poster of a Tamil movie Ponniyin Selvan-I prior to its release further points to the significance of Shiva in the cultural sphere of south India. The teaser of the film that showed Chola Kings, believed to be one of the strongest dynasties of southern India, wearing tilak instead of the sacred ashes that symbolise their Shaivite faith, took social media by storm. The historical connection of the Cholas with Shiva worship, along with the prominence of the Lingayats in Karnataka, scholars think, are some of the concerns that certainly drove the BJP towards redrafting their Shiva-alignment. Ajay Gudavarthy, professor in Political Science, Jawaharlal Nehru University, rightly calls it “BJP’s efforts to create a bridge to connect to the South”.

Amidst the promotion of Shiva as the newly discovered icon of Hindus, the Mahakal corridor is the third major upliftment project of a jyotirlinga site undertaken by the Modi government after the Vishwanath Temple in Varanasi and the Kedarnath shrine in Uttarakhand. The project at Ujjain is four times the size of the Varanasi project, which Modi inaugurated last year.

While Ujjain, referred to as Avantika in ancient times, has been a significant place of Hindu worship, Modi turning to its resident deity is considered by many to be a realignment of the politico-religious strategy of the BJP.

Since the 1980s, the BJP and the Sangh Parivar’s chosen deity for Hindutva politics has been Ram, the hero of the ancient Sanskrit epic Ramayana. A political campaign to construct a Ram Temple in the city of Ayodhya in the late 1980s, spearheaded by L.K. Advani, led to a resurgence in the party’s political fortunes.

According to social scientists and political analysts, in recent years, both Modi and his party spinmeisters have stressed their admiration for Shiva, who is a sort of subaltern God, popular with Dalits and Adivasis. It could be part of the BJP’s outreach project in these communities along with its efforts to accommodate the long-desired South within the mainstream pantheon of the north Indian politics.

Reclaiming an ancient site

The 4th-century Sanskrit epic poem Meghadutam by Kalidasa provides a description of the ancient Mahakal Temple at Ujjain. It is one of the 12 jyotirlingas. But it is different from other such temples because it is the only one in which the linga faces south. Surya Siddhanta, another 4th-century text on astronomy, claims that Ujjain is situated at the intersection of the zero meridian and the Tropic of Cancer, and many temples in the city are connected to time and space.

ALSO READ: Shiva In Mythology: Let’s Reimagine The Lord

In the 13th century, the ancient temple complex was allegedly destroyed by Shams-ud-Din Iltutmish, the third among the Mamluk kings, who ruled a part of north India. It was reconstructed in 1734 by Maratha general, Ranoji Shinde. Maharaj Jai Singh II also constructed an astronomical observatory called Jantar Mantar in Ujjain in the 18th century.

The current project plans to expand the premises of the Mahakaleshwar from 2.82 ha to 47 ha. This would also include 17 ha of the Rudrasagar lake. After the re-development, the annual footfall of pilgrims in the city is expected to go up from 1.5 crore currently to 3 crore.

A different sort of god

According to ancient Hindu scriptures, Shiva the destroyer is part of the trinity of the Hindu pantheon, including Brahma, the creator, and Vishnu, the preserver. Mythological sources show Shiva to be a sort of outsider among the gods, a consumer of intoxicants, who meditates in burning ghats.

The Bhagavat Purana narrates how Daksha Prajapati, one of the creators of the world, found him to be an unsuitable match for his daughter Sati. She, however, marries Shiva in a transgressive act interpreted as a subversion of the Brahminical sanctity.

“While Shiva is primarily located in the classical Hindu tradition, his disregard for commonly accepted social behaviour has subaltern connotations,” says Ayan Guha, assistant professor of Political Science, Jamia Hamdard University, New Delhi. Guha, who has authored the book, The Curious Trajectory of Caste in West Bengal: Chronicling Continuity and Change. He adds, “For Daksha, Shiva has no varna (caste). He is outside the social order.”

Guha points out that a contemporary manifestation of Shiva’s subaltern appeal can be found in ‘Kanwar Yatras’, which usually take place in the Hindu month of Shravan (July–August). During this month, pilgrims called kanwariyas—usually young men—walk hundreds of kilometres carrying holy water before ritualistically bathing a Shiva statue or linga in temples. According to a 2019 study by journalist Kalpana Jain for the Pulitzer Centre, “Decades-old Hindu Pilgrimage, Aided by Modi Government, Takes a Populist Turn”: “But the BJP’s strategy goes beyond cashing in on Shiva’s subaltern appeal. In recent years, the participation in Kanwar Yatras has increased and kanwariyas have become more aggressive, leading to clashes with people from other communities.”

An embodiment of Shiva

In 2017, Modi visited his hometown Vadnagar in Gujarat, about 70 kms north of the state capital of Gandhinagar, for the first time after he was elected prime minister in 2014. “Bholenath (Lord Shiva) is in Vadnagar, from where my journey started. He is in Kashi (Varanasi, his parliamentary constituency) too, where I have now reached,” Modi said.

ALSO READ: Shiva The Consciousness And The Bliss

Referring to Hindu mythology, he added, “Bholenath has the power to consume and digest poison. His blessings have given me the strength to digest all the poison that I have received since 2001. No matter who spews venom, I have the strength to serve the motherland.”

Identifying himself with Shiva was not mere symbolism. It was a deeper political metaphor echoed by some of Modi’s fellow members in the BJP. In 2021, Suresh Bharadwaj, minister of law and education in the Himachal Pradesh government, said, “We believe Shiva has reincarnated himself as Modiji.” Bharadwaj was referring to Modi’s two-day meditation in a cave in Kedarnath in 2019. Modi is not the only politician, however, to claim to be a devotee of Shiva. Congress leader, Rahul Gandhi, too, claimed to worship Shiva during the 2017 election to the Gujarat Assembly.

In June 2018, ahead of the assembly polls in Madhya Pradesh, Congress leader, Kamal Nath, also wrote a letter to the Lord of Time, Mahakal, complaining about 15 years of the BJP misrule. Such evocations of Shiva by different political parties reflect how he has turned out to be the most prominent icon of contemporary political discourse.

Subaltern politics

So, is Shiva replacing Ram in the political sphere for the BJP? “I think there are two things at work here, caste and regional coalition,” says Gudavarthy.

“Shiva is an ascetic and represents mostly non-caste Hindus, the tribals, the Dalits and also other backward classes. If you look at much of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the BJP’s ideological fountainhead, and other Hindu organisations are spreading their influence by hosting Shiv charchas,” Gudavarthy further says. These are informal village gatherings to discuss religious matters focused on Shiva.

Shiva is also popular in the southern states, where the BJP does not have much traction except Karnataka. “In the South, Ram is considered to be a north Indian, upper caste idol,” says Gudavarthy. “Few worship him besides the Brahmins. The Shaivite tradition is more popular in south India. In Sri Lankan mythology, Ravan is also a worshiper of Shiva.” He adds, “Leveraging Shiva might be a strategy to bridge the cultural difference in southern states, especially Karnataka and Telangana.” But is using Shiva to reach out to Adivasis in north India a new strategy? “Not really,” says Gudavarthy. “It has been going on for centuries.”

The larger Hindu nation

Uday Chandra, Assistant Professor of Government at Georgetown University, Qatar, characterises the attempts by the RSS and other Hindu organisations to incorporate Dalits and Adivasis into the larger Hindu fold as political Hinduism. “By becoming part of all-India traditions, Dalits and Adivasis have become political Hindus in the sense that Savarkar meant: atheistic, and the popular or laukik sense.” Vinayak Damodar Savarkar was a leader of the Hindu Mahasabha and one of the most influential Hindutva ideologues. “Every caste, tribe or community is now conceptualised as part of an Indian whole,” adds Chandra. “It is striking that male deities of the Brahminical pantheon are now being put into dialogue with marginalised communities, such as Adivasis,” says Chandra. “Note the absence of goddesses in this outreach effort.” He also says that Shiva’s ascetic aspects are emphasised less and he is imagined more as a ‘wild dimension’ of the Indic traditions. “That is why connections with forest-dwelling communities are made,” Chandra says. “We will wait and watch if the vegetarian Sangh Parivar will compromise with eating meat and drinking liquor as Shiva worshippers generally do.”

Beyond the binary of Ram and Shiva, Guha traces continuity in what he describes as ‘temple culture’, the spectacle of these large re-development projects of Hindu sites of worship. This does have an effect on people. Kuldeep, a dancer from Ayodhya, who travelled 900 kms west for the October 11 ceremony in Ujjain, says, “I like all temples, whether in Ayodhya or Ujjain. But who is renovating them? Modi, right?” Then he lets out the popular election refrain, derived from the worship cry for Shiva, for the prime minister: “Har, Har Modi.”

(This appeared in the print edition as "Making Political Capital")

Abhik Bhattacharya in Ujjain