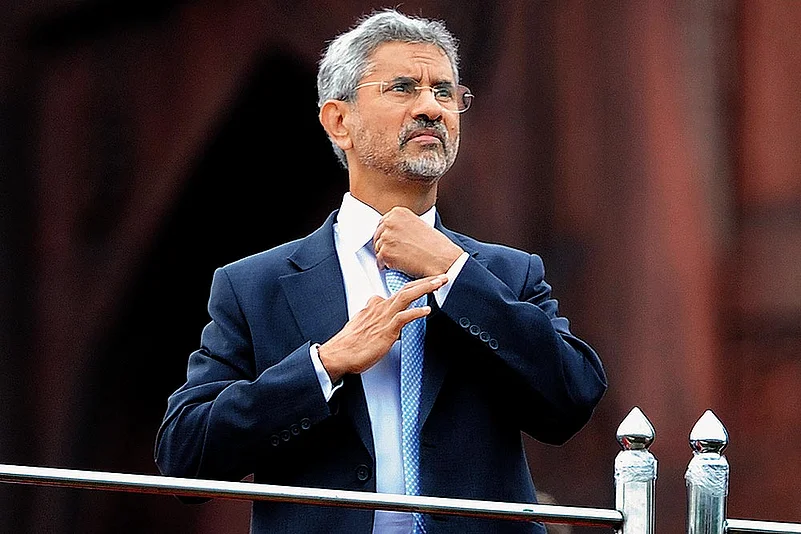

At a time when the world is being threatened with the advent of a ‘new cold war’ between the United States and China, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s decision to bring in 64-year-old Subrahmanyam Jaishankar as his foreign minister has become a major talking point in diplomatic circles in New Delhi and other world capitals.

Jaishankar, a 1977 batch Indian Foreign Service officer, was earlier handpicked by Modi to be the foreign secretary in January 2016. He went on to become one of the longest serving foreign secretaries in the country. In early 2018, he opted to join the corporate world—as president of Tata Sons Global Corporate Affairs, before giving up the lucrative job to join Modi’s cabinet. He had served as India’s ambassador in both China and the US.

In the past, many civil servants have opted to join politics either after resigning or retiring from their service. Some have been lucky to be included as members in the council of ministers. A few even moved up the political ladder either to become full-fledged ministers or important party functionaries. But none, so far, had been allowed to walk directly into the prime minister’s cabinet as a member.

On May 30, that long-standing practice was emphatically broken when diplomat-turned corporate honcho Jaishankar walked straight into PM Modi’s cabinet as his new external affairs minister.

Unlike other former bureaucrats, Jaishankar did not become a member of the ruling political party before being inducted. His was an unprecedented lateral entry—something some would say was scarcely imaginable.

One of Jaishankar’s predecessors, K. Natwar Singh, was the foreign minister in the UPA government led by PM Manmohan Singh. Natwar had also been a secretary in the MEA but he had joined the Congress after resigning from the IFS. Initially, he was the minister of state for foreign affairs but was subsequently promoted as the Union foreign minister in the Manmohan Singh cabinet.

The fact that PM Modi was willing to go the extra mile for Jaishankar was evident from 2016. Days before Jaishankar was to retire from the IFS, Modi made him the foreign secretary, cutting short incumbent secretary Sujatha Singh’s tenure by several months.

Only once before that had a serving foreign secretary so unceremoniously been removed. That was in 1987 when A.P. Venkateswaran was removed by then PM Rajiv Gandhi for publicly stating that sending Indian peacekeepers to Sri Lanka was a mistake. Still this was unique—Singh was removed to accommodate Jaishankar, who went on to serve as foreign secretary until January 2018.

Insiders say Jaishankar and Modi first met nearly a decade ago when the former was India’s ambassador in China and the latter, as Gujarat chief minister, was visiting the country. Modi had a successful visit and his Chinese hosts were impressed with him. The two met again when the envoy’s intervention was sought a few years later to help out some Gujarati diamond merchants who were detained by the Chinese authorities. The successful resolution of the crisis with the Indian ambassador’s intervention impressed Modi. Jaishankar was marked out by Modi as a highly competent diplomat. In subsequent years they got to know each other well and the trust and confidence developed further when Jaishankar was foreign secretary and had to work closely with Modi on several key challenges in the strategic and foreign policy domain.

For the next five years Jaishankar will be one of Modi’s close aides and a member of the exclusive team in the Cabinet Committee on Security (CCS). This apart, Jaishankar may be a much more visible and mobile foreign minister than what his predecessor Sushma Swaraj had been.

As one enjoying the PM’s confidence and unhindered by any political affiliation, Jaishankar could well be in a position to give dispassionate advice to the PM and his cabinet colleagues on key foreign policy challenges.

His vast experience in running the IFS for several years as well as his postings as ambassador in key missions will allow Jaishankar to give a wider perspective of what might serve India’s interests best, as he helps the prime minister chart the country through the increasingly choppy waters of global affairs.