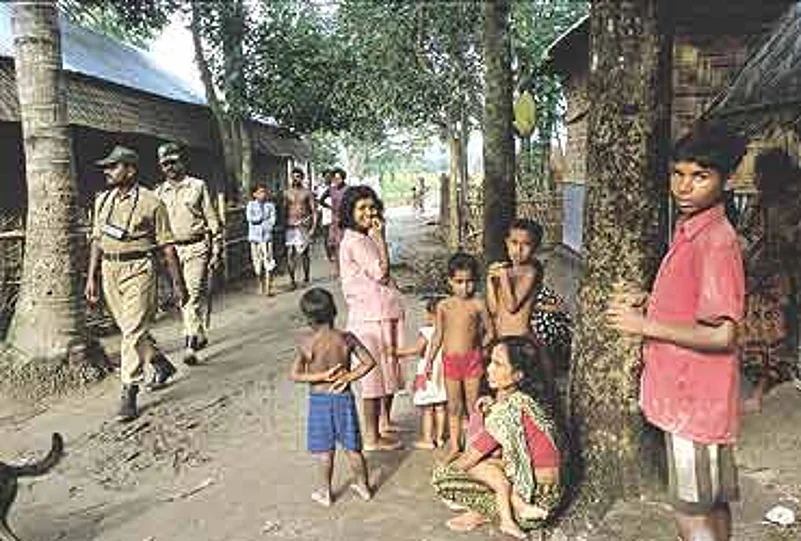

For people like these trapped between the border and the fence, it is like living in a prison. Outlook visited six of these villages—Khirkidanga, Antupara, Sipahipara, Bangalpara, Khudipara and Hindupara—to see for itself the plight of its people. The 700-odd residents of these villages can cross over to the mainland (or India, as they say now) through a gate that's manned round-the-clock by the BSF. The gates are opened three times a day: 6 am to 7 am, 10 am to 11 am and 4 pm to 5 pm. "Once the gates are shut, we are cut off from India and are at the mercy of Bangladesh. Very rarely does the BSF patrol our villages. We feel totally alienated. We are like stateless people without any identity," points out a despondent Dharma Deb Roy, a Hindupara denizen.

Not just that, the daily routine of entering their names in a register, subjecting themselves to frisking, laying out whatever they are carrying for inspection and having to account for everything they carry across the fence is something the villagers find humiliating and annoying. Some even see it as harassment. "We are citizens of India and nowhere else will you find people having to account for their movements or being subjected to inspection and strict vigil like us. Is it our fault that our villages are located here? Even if we purchase an extra kilo of rice or sugar for a special occasion, we have to provide an explanation. All of us have been detained for long hours at the gate, interrogated and our credentials and identity verified. Why should we face all this? We haven't committed any crime," says Shahamat Ali, a resident of Antupara that lies next to Khirkidanga.

To him and others, the BSF seems suspicious of them and even comes into their houses to inspect their belongings. If any villager is seen to even remotely defy a BSF jawan, he is beaten up. "My 12-year-old son, who studies in Class 7, was beaten black and blue by a BSF jawan a few days ago since he didn't dismount from the cycle while crossing the gate on his way to school," says a villager.

Many of the villages are emptying out. Hindupara once was home to 30 families, but only seven live there now. Those who could find buyers have sold their houses and lands, and left. The exodus will continue. Says Samir Roy of Hindupara, "I'm also saving money and plan to leave. It has become impossible to live here ever since the fence came up a few years ago. Our relatives have to provide an explanation to the BSF when they come to visit us. It's all very insulting. Life has become hellish."

West Bengal chief minister Buddhadeb Bhattacharya has been urging the Centre to make Bangladesh see reason. "I've taken up this issue with the prime minister, the external affairs minister and the home minister a number of times. Negotiations are on with Bangladesh. The fence is necessary, but it is also cutting off villages and families. The only way out is to construct the fence along the Zero Line. Let's see if Bangladesh agrees," says Buddhadeb.

Many, like state agriculture minister Kamal Guha, feel that if Bangladesh doesn't accept India's position, it should go ahead and construct the fence along the Zero Line anyway. Says Guha, "Lakhs of people who stay on either side of the fence have to cross it every day through gates manned by the BSF. The BSF opens these gates three times a day and this creates a lot of problems. Free movement is restricted. Aren't these people Indians, and doesn't our Constitution guarantee freedom of movement? Why should these poor and innocent people have to face harassment and even physical abuse at the hands of the BSF?"

The BSF denies the harassment charge. According to IG Tewari, his men do maintain a record of the people who cross the gate. He also admits that the villagers are frisked and any parcel or bag they carry is searched. But this, he maintains, is not harassment. "Our mandate is to check infiltration and smuggling. If we don't maintain vigil at the gates along the fence, the very purpose of constructing it would be defeated," he says.

But it's not as harmless as the BSF IG makes it out to be. Ask Maqbool Islam of Bangalpara. He was detained at the gate for three hours a few weeks ago by BSF jawans and was released only after the village elders reached the spot and certified that he was a resident. Complains Islam: "We have to seek permission from the BSF when we sell our produce in the markets on the other side (of the fence). On our way back from the markets, we have to account for everything we have bought, be it cattle, poultry, salt or soap." Islam believes the BSF views the villagers with suspicion and takes them to be smugglers.

The BSF admits to this scrutiny, but has its own perspective on the situation. Its officers point out that they have to ensure that people who cross the gates to come over to this side are Indians. It is not possible, they say, for a jawan to recognise the residents of the villages by face. "We never beat up anyone. We just question them if we're suspicious of their movements. We also have to check smuggling, and in order to do that, we have to maintain a record of everything that a person is carrying while crossing the gate," says B.S. Negi, commander of the A company of the BSF's 33 Battalion. He alleges that most of the villagers are involved in small-scale smuggling; essentials like sugar, grain and cooking oil fetch a premium in Bangladesh. So, if a villager takes extra rations, the BSF has reason to get suspicious.

On its part, the BSF has been requesting the state government to issue identity cards to the residents of the border villages. Senior officers point out that this will make things easier both for the BSF as well as the villagers. The state government says that the process of issuing ID cards has begun. But government action is invariably time-consuming. The BSF would also like the villages on the other side of the fence to be relocated. But land is not always available at close proximity. The only solution, then, is to construct the fence along the Zero Line.

Bangladesh is not likely to agree to that. The fate of lakhs of Indian villagers, then, lies solely in Dhaka's hands. Calcutta or New Delhi can do very little but pressure the Bangladeshi government. So far, they haven't been successful.