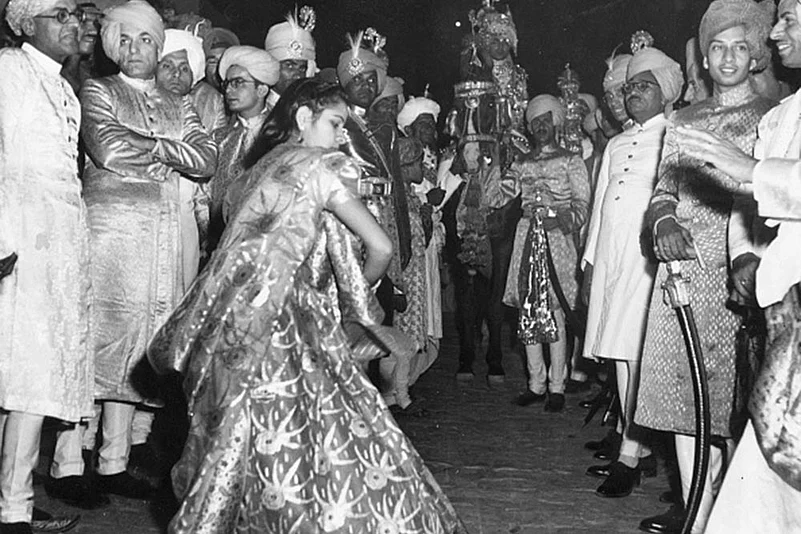

The big fat Indian wedding has once been in news recently with the heir of one of the most influential business families in the country tying the knot this year. The star studded pre-wedding festivities that were held earlier this month got widespread press coverage with everyone from global influencers to talk show hosts enjoying their slice of the great Indian wedding cake. For millions of Indian viewers, the festivities appeared like a dream from a Bollywood song. But under the veneer, all is not rosy. In India, where weddings are a source of aspirations and social mobility, the institution of marriage is as stratified as Indian society itself, riven with caste and class divisions. While the nation remains animated with the televised wedding bonanza, a newlywed Dalit man in Gujarat recalls his own wedding day with a tinge of pain.

On February 12 this year, a Dalit groom in Chadasana village in the Kalol district of Gujarat was dragged off his horse while he was heading to his wedding and abused by members of the dominant community. The victim, on condition of anonymity, states that a motorcycle-borne man crashed his baarat and slapped him while hurling casteist expletives. He was soon joined by three others, all of whom claimed that the groom needed permission to ride a horse to his wedding and that only upper caste men had that right. He was eventually forced to travel in a four-wheeler car instead. The groom’s family later filed an FIR and Gandhinagar police have arrested the four accused. The memory of that night hangs heavy in the groom’s memory. “It was quite traumatising. I had not expected something like that to happen on my wedding day, it was very unfortunate,” the man states.

The Gujarat case is not isolated. Cases of caste-based violence against Dalits for participating in celebrations like their own wedding is a recurring issue across India. In June 2023, a Dalit man’s wedding procession in Madhya Pradesh’s Chhatarpur district was attacked with stones and canes by members of the dominant community because the groom rode a horse. In 2019, a Dalit man was beaten up by dominant community men just for eating in front of them at a wedding reception.

“Sporting moustache, riding a horse in baarat, and generally leading a good lifestyle are all symbols of caste identity and pride among certain caste Hindus. When Dalits assert their identity or become equal to upper caste in status, some of the latter feel threatened enough to physically and violently attack people from marginalised castes in order to maintain the status quo,” says activist Beena Pallical, General Secretary at National Campaign on Dalit Human Rights. In March last year, the Centre informed Parliament that over 1.9 lakh cases of crimes against Dalits were registered in the four years from 2018. The data is not inclusive of systemic casteism and layers of micro-aggressions that Dalits face on a day to day basis. For instance, Dalits are often not allowed to wear footwear in certain so-called upper caste dominated areas.

Today, a host of television/OTT films and series tackle such questions of caste, Dalit aspirations and assertion, especially through the lens of love and the “great Indian wedding”. While one series recently depicted an elaborate Buddhist wedding that many Dalits opt for, another depicted the dilemma of a queer Dalit woman who chose to own up to her caste identity and sexuality, both of which she had hitherto been repressing.

In the real world, things aren’t as easy for couples choosing to stand up against caste hierarchies. Ashish Deokate and his wife Mansi, for instance, have been on the run for over three years. Ashish is Dalit while Mansi is OBC and her family does not accept the match. Ashish, an activist who has been involved in the ‘Right to Love’ campaign—which works to support intercaste and interfaith couples escaping conflict—says that caste-based honour killings are not uncommon in rural Maharashtra even today. The couple currently lives in a rented flat in an undisclosed location and does not stay in touch with their families.

Intercaste marriages have seen a rise and governments in several states offer cash incentives to couples who opt for interfaith marriages. But not all casteism is visible. In 2017, researcher Reena Kukreja studied inter-caste long distance marriages between Jat men living across 75 villages in Haryana and Dalit women who came as marriage migrants from other state. The study, titled Caste and Cross-region Marriages in Haryana, India: Experience of Dalit cross-region brides in Jat households, noted that while the practice ostensibly promotes progressive inter-caste weddings, they indeed uphold caste prejudices as the Jat in-laws often hide the daughter-in-law’s caste. She is not allowed to be in touch with her family for fear of her real caste being revealed among villagers and often faces discrimination that seeps down to her offsprings.

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Many young and educated Dalits today are opting for non-traditional weddings or rejecting the concept of marriage altogether and instead opting for civil unions as a way to reject the caste hierarchies that weddings often perpetuate. But without social safety nets or on ground implementation of anti-caste laws, caste assertion among Dalits remains largely dependent on the will and the socio-economic backgrounds of the couple involved.