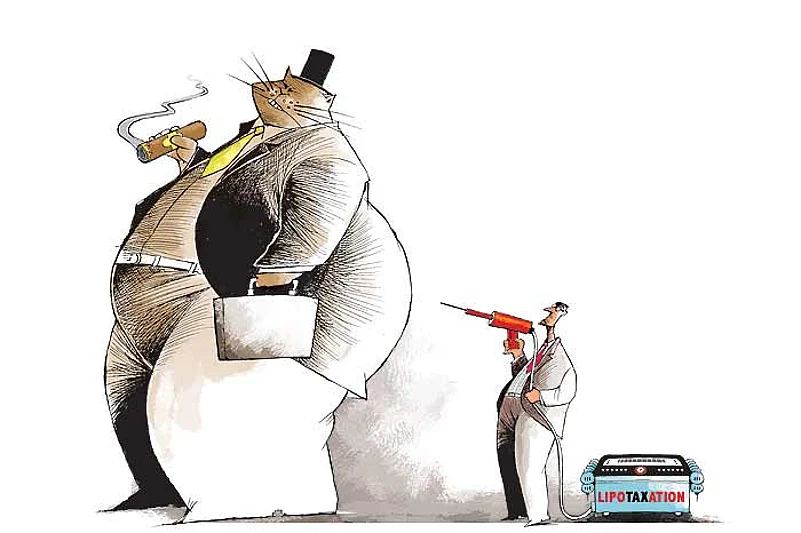

How The Rich Can Be Taxed

- Reintroduce marginal tax on inheritance, above a high threshold limit.

This tax is popular globally, but danger of loopholes being misused - Tweak the definition of Wealth Tax

The DTC has proposed 1% tax on net wealth over Rs 1 crore; wealth includes watches, trusts outside India etc - Increase taxes on luxury goods/services

Would need states to come on board, pan-India tax will take time - Tax rich farmers and non-farm rural income.

Farm incomes—and politics—don't justify taxes for now - Tax companies more, remove tax breaks on capital gains and dividends

DTC will up tax rates marginally; most exemptions and ‘holidays' will be history

Recent global cues

- France: Additional tax on income above 1 million euros being considered.

- US: Tax breaks for upper-income strata to expire in 2012, corporate tax loopholes to be plugged

- UK: To get £3-6 billion in taxes from illicit wealth stashed in Swiss banks

***

To talk about taxes is to bring about an air of unpleasantness. But to talk about taxing the “rich”—as did Union home minister P. Chidambaram last week—turns the dreary task of ferreting out resources into something more riveting. Particularly as earlier this year the former finance minister (note, not the current one) made a similar statement on the need to reintroduce an estate tax and called for taxing conspicuous consumption. Put together, these statements have struck fear into business. “I hope it was just an off-the-cuff remark, because I was utterly shocked by it. More taxes for the rich are just what we don’t need,” says Rajiv Kumar, director general, FICCI.

The very idea of taxing the rich has increasing popular appeal—these are not just copycat moves, like protests against bankers’ ‘excesses’ in the US. The clamour for it is also rising within the UPA, with political voices supporting higher taxes—one way or another—on wealthier people and corporates. Remember, the PM has earlier said businessmen should be austere; more recently, Union finance minister Pranab Mukherjee has stated in Parliament that a “wealth tax” on diesel for passenger vehicles is being considered. It’s obvious such statements resonate with the Gandhi family.

This is also in line with the global trend, with terms like ‘Robin Hood tax’ and ‘Buffett tax’ doing the rounds. In Spain, a wealth tax was proposed last month, and in France, a group of sixteen billionaires have voluntarily offered to pay more taxes. Numerous measures across Europe also signal significantly higher taxes on the rich.

Apr 18 ’11 Outlook’s piece on estate tax

“The fact that people who have more money can pay more (tax) is not a question,” says Dinesh Kanabar, who heads the direct tax practice for the business consultancy KPMG. “(The thing) to watch out for is whether higher tax rates remain conducive to growth, and to what extent taxes must be raised to be (considered) equitable,” he says. There is, however, no formula to figure out what an acceptable tax rate is. The FM can keep lowering the ‘slabs’ to the point of hitting the spot where a critical mass of voluntarily compliant taxpayers emerge. Or, he could hike taxes, and beyond a certain unknown level, economists say, individuals will be tempted to evade.

Since 1999-2000, tax revenues have grown 350 per cent, from Rs 1.7 lakh crore to Rs 6.4 lakh crore. Taxes are now 10.4 per cent of the GDP, compared with 8.8 per cent in 2000. Much of this improvement is credited to the removal or lowering of sundry levies, and widening of the numbers of taxpayers. Trouble is, at 30 million, the number of taxpayers remains abysmal for a country of 1.3 billion. This only fuels the drumbeat for quick results.

Since Budget 2011, exemptions granted during the slowdown in 2008 and 2009 were steadily withdrawn. New legislations, such as proposals for higher compensation to landowners whose property is acquired and the recent hike in mining royalty, have seen companies cotton on to the signal that more is expected of them.

Privately, several economists acknowledge the need for higher taxes on sections of the wealthy—such as those with inheritances. They say the idea behind this is that successive generations should not benefit solely because their parents were rich. “How is it in favour of equity if the son of a rich man automatically becomes wealthy?” asks a former finance ministry official and expert on tax matters, speaking on condition of anonymity. A reworked and stiffer wealth tax is also on the cards, courtesy the direct tax code (which will be introduced in 2012).

That Chidambaram’s comment is political is evinced by opposition parties’ responses to it. CPI general secretary D. Raja is suspicious of the move to ask the rich to pay more taxes—“It is the finance minister’s role, not Chidambaram’s, to comment on the economy”. Raja is also critical of the remark in the context of the corruption scandals that have led politicians (and businessmen, and executives) to prison. “But, who prevented the government from taxing the rich more so far? The Left has always asked for it—it is the UPA that never listened,” Raja says.

In the past, if you combined the income tax with wealth, gift, estate and luxury taxes, a rich man could have parted with 70 per cent or more of what he possessed. That is, provided he was not evading taxes. Today, the highest he’d pay is on par with what a middle-class earner would cough up—30 per cent of income above Rs 8 lakh at most.

“That’s why,” says Thomas Isaac, former finance minister of Kerala, “there is room for a marginal increase in the rate of taxes at the highest levels. I don’t think this (hike) will have an adverse impact on compliance. It will just bring us in line with international practice.” Isaac, a member of the CPI(M) central committee, warns, “Ultimately, not collecting enough tax will boomerang on any government—at least we can tax the top earners on par with global levels.”

In India, the battle cry to tax the wealthy comes at a time when the discussions to roll out the direct tax code and the goods and services tax (GST) are under way. Both these sets of rules focus on improving collection by widening the base and lowering the rate. Together, they will also try to do away with a host of other taxes, from excise duty to entertainment and luxury taxes—though only after the Centre and states agree on compensation for revenues that states stand to lose under such a tax regime.

“The bigger war underfoot is to phase out undue exemptions,” says former finance minister Yashwant Sinha, who is critical of the move to tax the wealthy. “The government’s long-term roadmap for raising revenues is clearly laid out, and the rich already pay much more tax than other taxpayers. By tinkering with rates now, I really can’t imagine what equity they hope to restore.” Sinha says Chidambaram sent a wrong signal by encouraging a “nebulous category called the rich” to be taxed more. “They’ll never identify the right category,” he says.

An obvious concern is that the new taxes would in no way dismantle an established industry that creatively evades taxes. From trusts to “sharing the spoils” with family members and sundry companies, there are numerous solutions we have all heard about. Even if the overall signal is clear—a roiling boil of taxes lie ahead—the government’s intent will be truly tested in the fine print.