In the past few years, media houses have been receiving a steady flow of CDs of illegally tapped phone conversations between politicians and their women friends, industrialists, fixers and journalists. These recordings arrive unsolicited, and most of them haven’t made it to the front pages or to the television screen. At best, they provided fodder for gossip in the news room or at parties. They’d soon be forgotten as unsubstantiated information.

Radiagate was different. The CD, with 140 conversations, was the outcome of the officially sanctioned tapping of lobbyist and public relations consultant Niira Radia’s conversations with industrialists, politicians, bureaucrats and senior journalists in 2008-09. With clearance from the Union home minister, the investigation cell of the income-tax department had tapped Radia’s phone and recorded more than 5,800 calls. The CD, containing fewer than a twentieth of those recordings, somehow came into the public domain and senior advocate Prashant Bhushan appended it to a public-interest litigation filed in the Supreme Court on November 15 seeking a probe into the 2G spectrum scam. Once out, the media could just not ignore it.

| “Ms Radia is doing her job as a lobbyist. The conversations reveal illegal acts and deals. They are not personal.” Prashant Bhushan, Advocate, Supreme Court |

| “Even if this talk took place inside the bedroom, we have a right to know. There is nothing personal about them.” Kamini Jaiswal, Advocate, Supreme Court | ||

| “These taps don’t deal with personal details but affect policy, governance. There’s nothing personal in them.” Arun Shourie, Ex-Union minister, BJP leader |

| “It’s sad the fourth estate has to deal with the public view that something is rotten inside. Public interest must win.” Subhash Kashyap, Centre for Policy Research | ||

| “I’m not comfortable with this. It’s not just about privacy. This has to do with state power, which mustn’t strip us of privacy.” Usha Ramanathan, Rights activist |

| “Privacy laws are subservient to public interest. But public interest must not be an excuse for harassing people.” Trilochan Shastry, Dean (Academics), IIM-B | ||

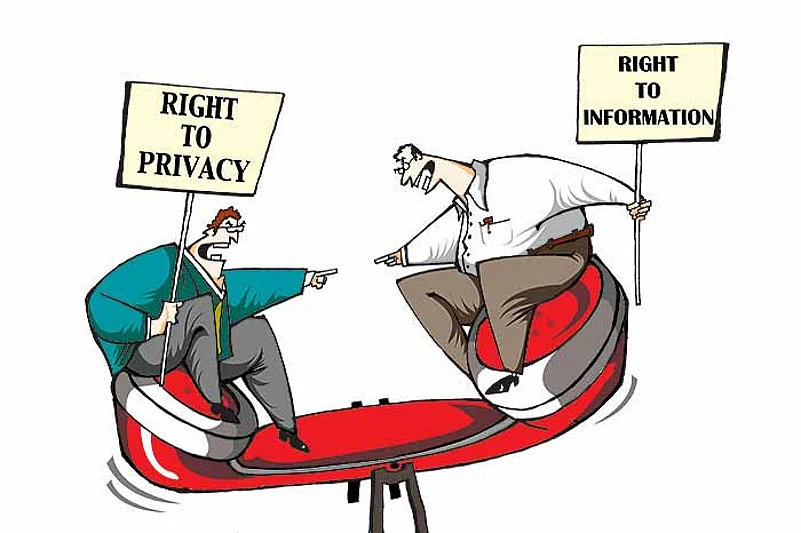

The outing of those conversations raises two questions for the media and citizens. First: Does the public have a right to know the contents of recordings (such as the Radia CD) that expose manipulation and corruption in high places? Second: Is there a privacy issue involved?

From the point of view of those who are on the recordings, there is indeed a breach of privacy: the contents, they say, should have been used only in the investigation of the particular case for which the tapping was authorised; there was no excuse for its reaching the public or the media, which is illegal. This is the objection Ratan Tata, chairman of the Tata Group, has raised in his November 22 petition to the Supreme Court seeking an injunction on transmission of those conversations in any form. Radia was handling public relations for Tata’s group and he figures in a conversation with her that has appeared in the media. His petition, it is learnt, raises serious questions about the privacy of individuals whose phones or other communication devices are tapped for investigation. Who orders tapping of phones? Are there any rules governing and circumscribing tapping? In the context of the privacy of the individual being investigated, how should public interest—the overarching justification for the expose—be defined?

It’s an important ethical question of balance in a democracy. Opinion is sharply divided. Senior advocate Dushyant Dave (who is not appearing for Tata) says Tata’s plea is not a matter of why the conversations were tapped but of how and why they were outed—questions he’s within his right to raise. But Arun Shourie, former Union minister and BJP leader, does not think there is any issue of privacy. “The 140 conversations in the public domain do not deal with personal details barring a reference to a black gown,” he says. “The contents affect policies and institutions of governance. Freedom of speech comes from the people’s right to know—to know how these institutions are functioning—and the taps are helping us understand how they actually function. There’s nothing private about them.”

NAC member and rights activist Aruna Roy says, “Public dealings are in the public domain and people have a right to know the mechanics of government and governance.” She refers to the Right to Information Act, propped by the pillars of transparency and accountability. The Whistleblowers Bill, too, throws a ray in that direction. It proposes that a public servant is within the law to bring departmental wrongdoings into the public domain if a) there is a cover-up or an attempt to cover up; b) the scale of wrongdoing transcends the scope and jurisdiction of his department.

The other point of contention is whether there is anything wrong in the conversations (which Tata says are private) reaching the media and being published. “Radia was hired in her professional capacity, and her dealings with her clients were in her professional capacity,” says Shourie. Dave concurs, and even invokes state security. “The right to privacy is subservient to the security of the state,” he says. “Security is also susceptible to the dangers from large-scale corruption and manipulation of the system of governance at a loss to the public exchequer—all of this, the public has a right to know.” He lists many court rulings, mostly from the Supreme Court, putting the right to information above the right to privacy.

And Bhushan, whose PIL draws some weight from the taps, says, “The black dress is a distraction—otherwise Ms Radia is doing her job as a lobbyist, influencing journalists and civil servants, and the conversations point to illegal acts and deals. The conversations with journalists are not personal and do have an impact on decision-making by the government.”

Kamini Jaiswal, a Supreme Court advocate, goes so far as to point out that evidence, even if it is illegally gathered, is evidence still. “The public has a right to know how it is being governed and these conversations tell us about that,” she says. “The income-tax department may have tapped Ms Radia’s phone for information on money transactions, but what has emerged is of far more serious consequences. So, even if these conversations had taken place in a bedroom, the public would be within its right to know what they are about because there’s nothing personal in them.”

So, are we forfeiting our right to privacy to the state? Usha Ramanathan, a rights activist, highlights the dangers. “I’m not comfortable with what has happened,” she says. “It’s not just the right to privacy. It also has to do with state power. Even the right to information has evolved with certain logic—the accountability of public authority to the people. But it’s not for stripping away the privacy of people. I think we are handing away all the powers to the state.”

The real threat however, some say, may well be to the media. What if the courts stop the publication of reports on the matter, pending investigation? Will that, they ask, be the benchmark for investigative journalism that makes the government uncomfortable? After all, the media occupies a space between the people and the government, and this link is in danger of being weakened. But Shourie lays such fears to rest: “Has the mighty US been able to stop Wikileaks?” There’s some comfort in that thought.