A2,000-year-old fossil excavated from under layers of mental sediment? Ancient wisdom, with the dust of theages brushed off? Or an enervated, yet undoubtedly extant, performance tradition fattened for the show—a sort of Jurassic-scale museum piece for public display?

The resurrection in question (and it, indeed, is in question) is that of a theatre-house based on Natyashastra guidelines. The show: Tridhara, a five-hour-long performance of three ancient plays in the specially built Vikrishta Madhyam auditorium. The question: is it really after so many centuries that a Natyashastra-abiding arena for theatre has come along?

Whatever the answer, Rita Ganguly, seniormost faculty member at the National School of Drama (NSD), Delhi, has undertaken a truly monumental project with the second year students. If Vikrishta Madhyam is history, live, what about the kuttambalam in which Kudiyattam is performed?

"A kuttambalam is a natya mandap attached to a temple and not used exclusively for theatre," clarifies Ganguly. "A natyagriha or a prekshagriha are different: these are used exclusively for theatre."

The structure subscribes to one of the nine theatre-types held possible in Natyashastra: vikrishta is rectangular and madhyam refers to the medium size. This facsimile of a traditional performing space had its birth pangs. Sadly, after all the trouble, the NSD may not be allowed to retain the structure which has come up on the NSD lawn with some help from HUDCO. The Horticulture Department has suddenly grown fond of the NSD lawn, which has, for the last five years at least, remained more of a dustbowl.

Though Vikrishta Madhyam's floor is more or less pucca, its pillars and roof are not. A large cloth painted over with works loosely suggestive of the Ajanta-Ellora school of art, covers the seating portion and two raised platforms on stage. Jute and cement pillars evoke the sculpted columns of traditional theatre. No chairs greet the audience—just large expanses of sheets spread over mattresses, with gau takkias or bolsters for people to recline upon. There are no walls. Coal-lit braziers line the seating area to cut the chill in the evening air.

Tridhara is quite an experience. The three plays, Kalidasa's classic Abhijnana Shakuntalam in Sanskrit, and Boddhayana's Bhagavadajjukiyam and Vishakhadatta's Mudrarakshasa translated into Hindi, brought to life classic theatre concepts.

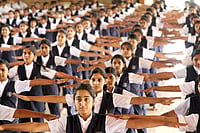

A near-packed hall was held spellbound for five hours. Fears vis-a-vis Sanskrit were unfounded—the language was the least part of the experience. The hand gestures (hasta) and the acting (natya) were enough to make the text easy to follow.

"Our tradition holds with an entire night of theatre," says Ganguly. "In fact, a play goes on for three to nine nights. But we're doing excerpts, three excerpts to highlight three vrittis (styles): love in Shakuntalam, comedy and farce in Bhagavadajjukiyam and statecraft in Mudrarakshasa."

Abhijnana Shakuntalam used miniature paintings (chitra-abhinaya) as points of reference. Ganguly framed Shakuntala during the high points of the action. Correlating this to modern day techniques, one could not but help think of a cinematic close-up.

Bhagavadajjukiyam, a tale of transposed souls (between a holy man and a courtesan), had the audience in splits. Mudrarakshasa, on the contrary, had few light moments. Apparently the only Sanskrit play written on a political theme, it has a Machiavellian plot highlighting the political savvy of Chanakya Vishnugupta.

Rehearsals for six months, 18 hours a day, went into the tasteful production. But if the arena goes, where does the action go?