Once upon a time in Bollywood, the first thing an A-list star would ask script-writers was if it contained any sequence to be shot on foreign locations. In days of yore, a majority of formula flicks had to have scope for such pizzazz-enhancing scenes. If there were none, an indulgent producer would get something exotic interpolated in the narrative—a dream song set amidst snow-capped mountains around Zurich, say, or a romantic interlude where the lead pair would wade through tulips near Amsterdam, or an edge-of-the-seat car chase on a Parisian street—to keep the lead actor in good humour. An idyllic European getaway would take the hero far away from Mumbai’s grime and cut short his malingering too, thus helping the producer finish his film on time—a mutually beneficial arrangement.

Much water has flown under London’s Tower Bridge since then. The scenes have shifted; they have a starkly different backcloth now. Last month, superstar Akshay Kumar wrapped up the shooting of his next release, Toilet: Ek Prem Katha, in the dusty villages of Mathura in Uttar Pradesh, and followed it up with an extended outdoor schedule for the upcoming Padman, in Indore, Hoshangabad and Bhopal, braving Madhya Pradesh’s energy-sapping temperatures.

Going by the number of movies being shot at smaller centres, foreign locales seem to hold fewer charms for Bollywood stars. Howsoever popular, they are now ready to explore hitherto nondescript places up-country, doing their bit to lend an authentic look and feel of real locations to their films.

Akshay Kumar’s Toilet: Ek Prem Katha was shot in Mathura

Even before Akshay, Bollywood’s hit machine, hit the dusty trail in the country’s ‘cow belt’, he had already shot this year’s blockbuster, Jolly LLB 2, in a start-to-finish schedule in and around Lucknow. Earlier, Salman Khan, too, had landed in a hamlet at Morna, a suburb of Muzaffarnagar district in UP, to shoot for Sultan. The new, unspoken rule in the industry reads thus: if the script demands, the stars and film-makers will prefer to shoot on actual locations rather than on artificial sets erected at a Mumbai studio.

It’s a wild deviation from the past, when any outdoor location beyond the Madh Island and China Creek in Bombay would mean picturesque locales of Pehalgam, Gulmarg, Manali or Ooty, if not the Swiss Alps. It was unthinkable then that a mainstream movie could be shot in Jhansi, Kota, Meerut, Patna or even Dumka, a tribal district tucked away in the hinterland of Jharkhand.

Such things are de rigueur now. Apart from movies being written around subaltern characters, they are also being named after small towns—like Bareilly ki Barfi and Anaarkali of Aarah—to underline the growing importance of such places in Bollywood’s new business model. These days, Farhan Akhtar is shooting Lucknow Central in the UP capital for greater authenticity, something he could easily have done in Mumbai’s Film City. Anurag Kashyap and Ashwini Iyer-Tiwari have just finished shooting their next releases, Mukkebaaz and Bareilly ki Barfi in Bareilly. That town in UP could have been ‘created’ without any fuss by any Mumbai art director. But the film-makers want to capture the real, flavourful Bareilly, an otherwise sleepy town without a filmy connect, the glorious exception, of course, being that one hit song from Mera Saaya (1966).

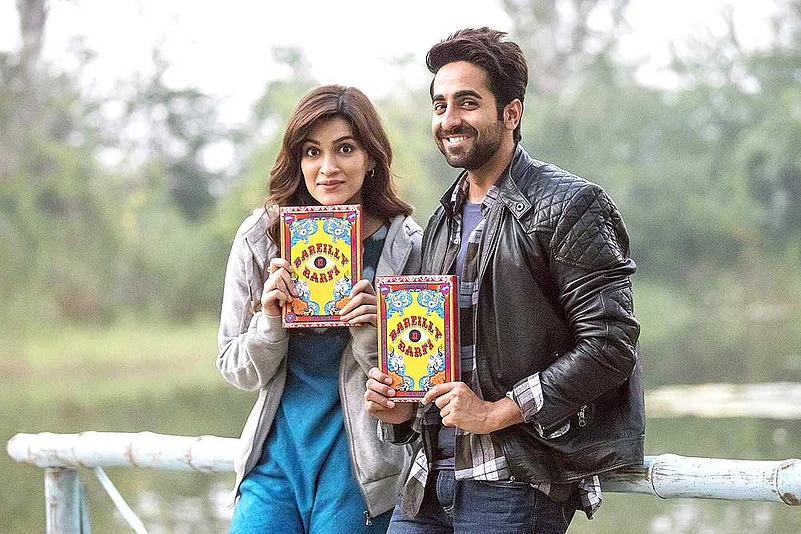

Quite surprisingly, Bareilly has emerged as a much sought-after location, with more scripts being written about small-town boys and girls. After Hansal Mehta’s Manoj Bajpayee-Rajkummar Rao starrer Aligarh was canned there, Ashwiny Iyer-Tiwari, who directed Nil Battey Sannata (2016), shot her next venture at Bareilly too—a film called Bareilly ki Barfi, starring Kriti Sanon, Ayushmann Khuranna and Rajkummar Rao. “My film is a love story, a rom-com, a slice-of-life story based in Bareilly and Lucknow,” Iyer-Tiwari tells Outlook. “It is not as though romance does not take place in small towns like Bareilly. By shooting my film there, I have tried to ensure a realistic context.”

A still from Bareilly ki Barfi

Iyer-Tiwari, whose directorial debut last year was widely acclaimed, says India has always been a country whose culture is rooted in small towns. “Everyone who comes to metropolitan cities is from a small town,” she says. “As film-makers, if we do not talk about such towns and their cultures, who will?” she asks.

Iyer-Tiwari, whose director-husband Nitesh Tiwari’s Dangal (2016) rewrote box-office records, says most copy-writers she worked with during her stint in advertising belonged to towns in states like Madhya Pradesh and Bihar. “In those days, we used to travel to Lucknow, Bhopal, Coimbatore, Rae Bareli and other places for research on consumer products. If we could go to such towns for research, why can’t we go there for shooting films? After all, we get so much insight into various cultures from such places, something we do not find in Mumbai and Delhi,” she points out.

Bollywood analysts believe that changing profiles of film-makers, as well as the audience, have contributed a great deal towards this paradigm shift. Avinash Das, director of Anaarkali of Aarah, says that the internet revolution has made cinema easily accessible to people from smaller towns and, in turn, has opened the gates of tinsel town for them in more ways than one. “First of all, cinema is easily available to people living in the smallest towns and districts these days. Access to the best international movies is no longer the exclusive domain of only a select group. Now, residents of small towns such as Madhubani and Darbhanga (in Bihar) can easily watch them,” says Das, whose debut film depicted the tales of a singer-dancer from Ara in Bihar, his native state. “This has brought about a whole new world of difference to new cinema in the country.”

“The stories of small towns and kasbas which were never told before are being told on screen now. People arrive in Mumbai from smaller towns with fresh ideas and stories to pursue their dreams,” says Das. “Film-makers such as Anurag Kashyap, Tigmanshu Dhulia, Anand L. Rai et al have told the stories of their region to make a big impact. The number of such people will grow in future and the content of Indian cinema will get richer by the day.”

It is true that the rise of film-makers from the Hindi heartland in general and UP in particular has given a tremendous boost to what can be called small-town cinema. The movies of Anurag Kashyap (Gangs of Wasseypur), Anand L. Rai (Raanjhana, Tanu Weds Manu and its mega-hit sequel), Hansal Mehta (Aligarh) Subhash Kapoor (Jolly LLB) and Tigmanshu Dhulia (Pan Singh Tomar) have helped evolved a genre that Bollywood had never considered a safe business proposition.

Film writer Vinod Anupam asserts that the rise of middle class and their spending capacity in the post-liberalisation era, coupled with the emergence of cheaper, digital technology, are responsible for the rise of small town-centric films. “Cinema has to cater to the emerging markets, dependent on middle class audiences,” he says. “Besides, in an era when movies are shown on five different screens in a single multiplex, film-makers have to come up with different stories. They cannot afford to make movies on the same formulaic themes as they did way back in the 1970s,” adds Anupam.

The national award-winning writer says that new stories invariably come from smaller towns and not from metropolitan cities, where people lead predictable and monotonous lives. “Half Girlfriend depicts the tale of a boy from Buxar, not somebody from Bandra,” he says. Unlike in the past, when film making was the exclusive right of a few families, says Anupam, a new generation of film-makers like Anurag Kashyap has taken over to tell their own stories. “They have made their presence felt without surrendering to the diktats of Bollywood.”

The cast in Hindi Medium

In fact, the two movies releasing this week, Half Girlfriend and Hindi Medium, reflect the sense and sensibilities of a rapidly expanding middle-class society. While Half Girlfriend, based on Chetan Bhagat’s best-seller of the same name, traces the journey of a Bihar youth bereft of conversational skills in English, Hindi Medium is all about the desperation of parents to get their child admitted into any English medium school by any means, as they believe it to be the shortest way to climb up the social ladder. Their makers apparently believe that the audience from small towns would instantly relate to such themes.

Trade analysts, however, also attribute another reason to the rise in the number of small town movies: the incentives being given by state governments. “UP and many other governments such as Jharkhand have started giving subsidies for shooting in their states,” says Das. “This not only helps promote the cinema industry but also boosts local tourism and other related sectors, besides generating employment.”

Recently, the Jharkhand government provided substantial cash incentive to the Bhatts of Vishesh Films for shooting a large portion of Begum Jaan, a Vidya Balan-starrer, at Ranishwar block in Dumka district. The movie was also declared tax-free to give it a further boost. The UP government has also been giving an incentive of up to Rs 2 crore for shooting 50 per cent of the film in the state.

But then, such incentives may be pittance for big film-makers such as Aditya Chopra and Karan Johar, who have also shot their movies in different UP and Uttarakhand towns such as Kota, Jhansi and Haridwar for films like Sultan, Dum Laga ke Haisha and Badrinath ki Dulhania. Boney Kapoor also took the entire unit of Tevar to Mathura to shoot major portions of the film. And then, there are film-makers such as Ketan Mehta, who spent months in Gaya to shoot Manjhi: The Mountain Man, the biopic of Dashrath Manjhi, in and around his native Gellour village, without getting any incentive from Bihar government, except a tax free status after its release.

It is not as though Bollywood films had never been shot in UP and Bihar. Varanasi and Agra have remained perennial favourites of film-makers. But they used to be wary of shooting at smaller centres in the past, primarily because of unruly crowds. The Bihar police once had a tough time during the shooting of a song of Johny Mera Naam—picturised on Dev Anand and Hema Malini—at Nalanda and Rajgir way back in 1969.

Greater exposure to stars across several platforms appear to have changed things for the better. Iyer-Tiwari, who shot her first film in Agra and faced some issues of crowd management, says her recent Bareilly schedule passed off like a breeze. “The locals even used to send food for the unit and offer their houses for rest,” she says.

For all their local, earthy allure, will the small-town phenomenon last? Given the box office returns of the small town-based movies such as Badrinath ki Dulhania, which turned out to be a blockbuster this year, Bollywood’s march into the interiors, as of now, looks irreversible. “The middle class, the biggest patron of such films, is not going to shrink in future, nor will new technologies to make movies get dearer,” says Das. “These factors indicate that small town-centric movies will not prove to be just a passing fad.”