As I write this, several terrible accounts of the sweeping pandemic have emerged from rural parts of the country—among them, shocking visuals of dead bodies in the Ganges from parts of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. As we feared and foretold, COVID-19 has left vast swathes of rural India gasping for breath. Since last year, the threat of this virus ravaging the hinterland economies has been looming large. That is now coming true.

As the virus wreaks continuous havoc, I am besieged with desperate calls for help not only from the people of my home state, Bihar, but from all over the country. Like innumerable citizens affected by the deadly pandemic, I too have been trying to amplify SOS calls for help on social media platforms, drawing on personal networks of colleagues, civil society organisations and conscientious, hardworking students to mobilise resources and relief, and imploring the ruling class and the bureaucracy to be more visible, active and empathetic in coming to the aid of those going through unprecedented suffering.

ALSO READ: Twice Orphaned

The absence of a coherent, timely and well-thought policy is shocking. It is said that failure to plan equals planning to fail. The government squandered precious time late last year, ignored and defied expert advice, and was found napping at the wheel. The unfortunate part, of course, is that they weren’t napping; they were pouring in immense resources and political capital in pushing through anti-people policies and laws. The vaccine policy is poorly planned, and the shortages compound the disastrous impact of the pandemic.

Precious time was lost due to the hubris, and lack of perspective and empathy among the top government leadership. Parliament was not allowed to function, let alone those in power be questioned. From high courts to the Supreme Court of India, the judiciary has had to intervene to monitor even essential executive functions and ensure they are carried out. Additionally, critique and dissent have been criminalised; even reporting facts has become a dangerous proposition for experts, public officers and honest journalists. With all the sloganeering around ‘Minimum Government, Maximum Governance’, ‘Cooperative Federalism’ and ‘Aatmanirbhar Bharat’, powers have been so strongly centralised that even the capacity to allocate the meagre but extremely useful provisioning of basic MPLADS funds has been taken away from parliamentarians. With access to these funds, the MPs would have made significant interventions in their constituencies, predominantly rural districts, which is where the pandemic will hit the most.

ALSO READ: The Empire Of Cruelty

While the concerns of the urban parts are being heard and duly noted on social media platforms, the rural parts of the country largely remain absent from the discourse. The urban and the rural poor are still reeling under distress caused by the lockdown last year. Here it is essential to note that our economy was still healing from the devastating impact of the demonetisation undertaken in 2016 when Covid struck us.

What Covid did, in economic terms, was to add to existing woes, especially of the poor. With the compounding health costs that Covid demands, and the overall disruptions caused by the lockdown to agricultural supply chains, there is now mounting pressure on the marginalised. These include, most notably, farmers, women and children, the elderly, the specially abled, transgender people, poor frontline workers, and the vast, unquantified workforce in the informal sector and the peripheries of India—rural or urban. More so because the present mutant strain threatens the young population, once touted as India’s demographic dividend.

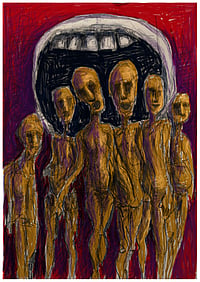

ALSO READ: The Seventh Seal

However, one needs to seriously consider the unimaginable impact of this crisis on rural areas, where 65 per cent of the Indian population lives. Lack of adequate resources, a crippling public health infrastructure and inadequate water sanitation services are just a few factors that should have been enough to alert the government, as early as March 2020, of the consequences of the pandemic spreading into the hinterland. The rural parts of India are anyway characterised by lack of water, dependency of agriculture on the monsoons and the vagaries of weather. Consequently, the threat of recurrent drought mars the economic health of agricultural zones. Similarly, the agrarian crisis resulting in farmer suicides is a deeper problem that has been ignored. Covid may just exacerbate these indicators, and there is a lack of communication from the government in this regard.

Some 86 per cent of Indian agriculture is peopled by small and marginal farmers. Many field experts believe the economic disruptions caused by Covid may affect the number of farmers dying by suicide, owing to the financial losses that will now ensue, and the mental breakdown and alienation. Handicraft- and handloom-based livelihoods have already been severely impacted by the pandemic and the recurrent lockdowns—remember, textiles and handicrafts employ the second largest workforce after the agricultural sector. Again, the sector was already reeling from the body blow it received during demonetisation. To make matters worse, the government abolished the Handlooms and Handicrafts Board in the middle of last year, exactly when artisans and self-help groups (SHGs) needed governmental support the most.

ALSO READ: The Complete Covid Chargesheet

On public health infrastructure, a September 2020 article on India Water Portal mentions how 23 per cent of India’s villages don’t have a primary healthcare centre. More importantly, with a meagre spend of 1.26 per cent of the GDP on healthcare—as reported earlier this year—and a crippling public health and water sanitation infrastructure in rural districts, Covid threatens to uproot the flailing equilibrium of both rural and urban India. One doesn’t need much statistics here as the myriad heart-wrenching visuals of people collapsing outside Delhi’s hospitals and on the streets are enough for anyone to gauge the magnitude of the problem. Lack of oxygen, oxygen infrastructure like cylinders, masks, medicines or timely assistance, and flooded hospitals and surge-priced ambulances don’t augur well for ‘Bharat’—or the ‘other India’ away from the world of policymakers, media and the political leadership. Add to these an overburdened workforce of Anganwadi and ASHA workers—the real footsoldiers on the ground catering to people and filling in as a frontline workforce—and the infrastructural shortages at government hospitals.

ALSO READ: Jantar Mantar Is Just A Sundial. Period

Additionally, the impact on rural livelihoods with MGNREGA works being stalled during the lockdown last year—which was announced without any coherent or holistic policy to safeguard poor urban livelihoods—needs to be considered for an urgent intervention. A robust strategy around MGNREGA-Plus is the need of the hour. It would also serve the government’s political capital if they put all its weight behind the scheme, leaving aside the politics about who initiated this life-saving scheme for the most vulnerable section of our population. (Just for the sake of refreshing public memory, it was the RJD under UPA-1 that was instrumental in rolling out and steering this transformative instrument of basic rural welfare.) However, the besieged are still waiting for their PM to condole the losses.

Since the virus knows no borders, it is vital that we ramp up medical infrastructure in the villages on an urgent basis. Corporate Social Responsibility funds must be utilised in this regard. A battery of doctors catering to the rural areas specifically needs to be roped in before it becomes too late. Perhaps this is the right time to make the infrastructure so robust that, in the future, doctors and health professionals willingly volunteer to serve in the hinterlands. Proper tracing, testing, awareness and sensitisation around vaccination needs to be undertaken in the villages, in addition to ramping up Covid-care facilities like isolation and quarantine centres to mitigate its spread. Finally, with respect to India’s food security targets, the Public Distribution System needs to be universalised immediately.

ALSO READ:

The writer is a Rajya Sabha MP from the RJD. views are personal.