Summary of this article

Dr Syed Qasim Rasool Ilyas demanded accountability from investigating officers in cases that collapse after years of incarceration

Under the UAPA, bail provisions are stringent, and trials often take years to begin in earnest

Those responsible for filing "voluminous and baseless chargesheets" must also face consequences, said Dr Ilyas

“Bail is the rule, jail the exception except for my son.”

Dr Syed Qasim Rasool Ilyas began with that line and for a moment the packed hall at the Marathi Patrakar Sangh fell into complete silence. His voice trembled but did not falter. Inside, every chair was occupied. People stood shoulder to shoulder along the walls. Outside, a small crowd gathered at the entrance, some peeping through the half open doors, others listening from the corridor. The 9th Shahid Azmi Memorial Lecture had drawn far more people than the hall could contain. Lawyers, activists, students, former prisoners, families of the incarcerated and members of civil society had assembled, not only to remember Advocate Shahid Azmi but to reflect on what many described as a deepening crisis within the criminal justice system.

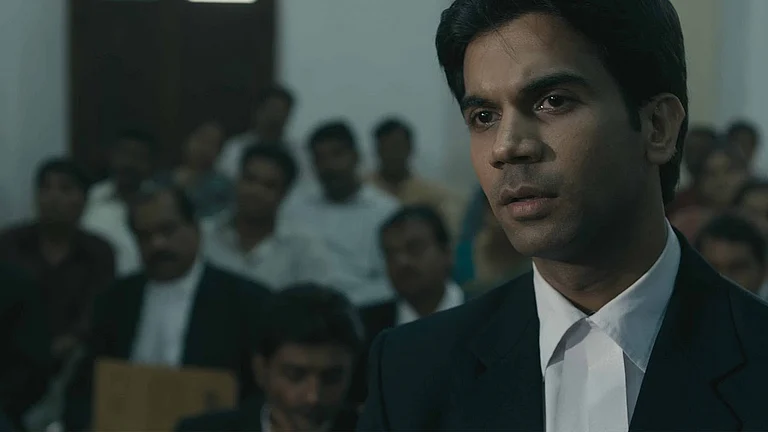

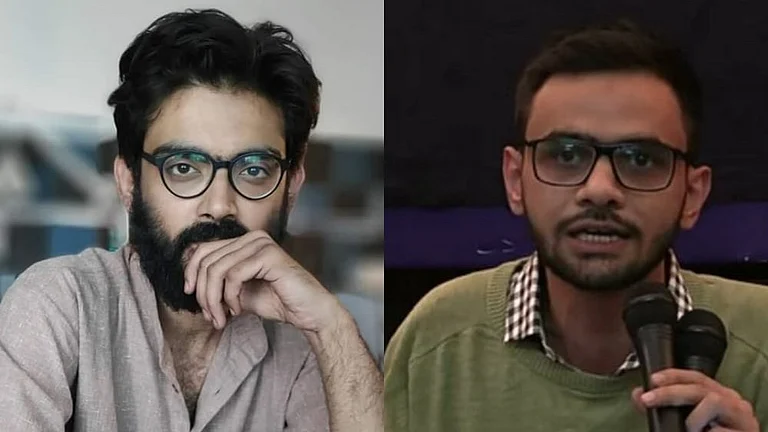

Organised by Innocence Network India, the lecture focused this year on the prolonged denial of bail to Umar Khalid and Sharjeel Imam, both charged under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act in connection with the 2020 Delhi riots conspiracy case. More than five years have passed since their arrest. They remain undertrials.

For Dr Ilyas, the evening was both personal and political. He spoke of the family’s repeated attempts to secure bail, including approaching the Supreme Court several times. He referred to public remarks made after retirement by former Chief Justice of India D Y Chandrachud reiterating a long standing judicial principle that bail is the rule and jail the exception. “We hear this principle quoted again and again,” Ilyas said. “But in Umar’s and Sharjeel’s case, it seems bail has become the exception and jail the rule.”

He described the emotional toll of watching years pass while the trial inches forward. Khalid, he said, had declined two foreign university scholarships because he wanted to work in India and had not even applied for a passport. “He chose to stay in this country and dedicate his life to it,” Ilyas said. “Today he remains behind bars without the trial concluding.”

Much of his criticism centred on the scale and structure of the prosecution. Referring to a charge sheet that reportedly runs into nearly 30,000 pages and lists more than 900 witnesses, he questioned how any trial could reasonably conclude within a foreseeable time frame. “Does this even make sense?” he asked. “At this pace, will the case conclude in Umar’s lifetime?”

He went further, demanding statutory accountability for investigating officers in cases that collapse after years of incarceration. If an accused is acquitted after a decade or more, he argued, those responsible for filing what he described as voluminous and baseless chargesheets must also face consequences. The suggestion was greeted with murmurs of agreement from sections of the audience, many of whom have lived through long legal battles themselves.

Asif Mujtaba, introduced as a friend of Sharjeel Imam and a co-organiser of the anti CAA protests at Shaheen Bagh, broadened the discussion beyond individual cases. He revisited the political climate preceding the February 2020 violence in north east Delhi and questioned how the narrative of conspiracy had taken shape.

Mujtaba argued that speeches delivered during the anti CAA movement were selectively quoted and stripped of context in order to construct a sweeping theory of orchestration. According to him, what began as a decentralised mass protest led largely by women in Shaheen Bagh was gradually reframed as a coordinated plot. “Participation in a political movement is being reinterpreted as criminal conspiracy,” he said.

He marked the passage of time with stark precision. “As of today, Sharjeel Imam has been in jail for over 2,200 days,” he told the audience. The number hung heavily in the air.

It was Mujtaba who referred to BJP leader Kapil Mishra’s alleged speech in north east Delhi shortly before violence broke out. He noted that Mishra now holds ministerial office and contrasted that with the continued incarceration of Khalid and Imam. Pointing out that a majority of those killed in the riots were Muslims, Mujtaba posed a question that drew a long silence. “If most of the victims were Muslims, did Muslims kill only Muslims?” he asked, suggesting that the distribution of accountability did not align, in his view, with the distribution of suffering.

Mujtaba also re-narrated developments in the Delhi High Court during the early days of the violence. He recalled the late-night hearing before Justice S Muralidhar in February 2020, when strong observations were reportedly made about alleged hate speeches and the role of the police. He spoke about the subsequent transfer of Justice Muralidhar, describing it as abrupt and coming at a critical moment. According to Mujtaba, there was widespread public perception that had immediate action been taken against those accused of delivering inflammatory speeches, events might have unfolded differently. He framed these developments as part of a broader pattern of institutional response during moments of communal tension.

The evening repeatedly returned to the theme of delay as punishment. Under the UAPA, bail provisions are stringent, and trials often take years to begin in earnest. For families, speakers said, time itself becomes a form of incarceration.

Sanobar Keshwaa, Shahid Azmi’s former teacher at KC Law College, offered a moving recollection of him as a student.

“He did not come to college very often,” she said with a faint smile. “But whenever he did, his participation was incomparable.” She described him as thoughtful, intense and unafraid to speak.

She recounted a classroom exercise in which she had asked students to narrate the most horrific incident of their lives. Shahid, then recalling his adolescence, spoke about the aftermath of the 1992 blasts when, at the age of 14, a policeman allegedly pointed a gun at his head. “He said it made his spine shiver,” Keshwaa remembered.

She went on to describe how he later travelled to Kashmir believing he was being called for training, only to realise upon reaching there that it was not the path he wished to follow. On his return journey, he was arrested, detained in the Red Fort complex, allegedly tortured and eventually transferred to Tihar Jail as a juvenile. “Who would have known,” she said quietly, “that this boy would come out and become a voice for human rights?”

Azmi went on to represent several individuals accused in terror cases, many of whom were later acquitted after years in prison. For many in the hall, his life symbolised the possibility of reclaiming dignity and purpose after injustice.

The composition of the audience reflected that history. Among those present were individuals out on bail in the Bhima Koregaon case, often referred to as the BK 16, including Sudha Bharadwaj, Vernon Gonsalves, and Hany Babu. There were also people who had faced incarceration in cases such as the 7/11 Mumbai train blasts before eventually being acquitted. Some sat quietly taking notes. Others listened with folded arms. A few wiped away tears.

Case files and court orders, several attendees remarked, have become constant companions over the years. The memorial, in that sense, felt less like a formal lecture and more like a gathering of those bound by shared experience. The room was not only full of people but of stories, each marked by adjournments, appeals and waiting.

As the programme concluded, no one seemed in a hurry to leave. Small groups formed inside the hall and in the corridor outside. Those who had been standing outside finally stepped in as the crowd thinned slightly. Conversations continued in hushed but urgent tones.

What lingered was not only the memory of Shahid Azmi but the questions raised through the evening. What does it mean when undertrials spend five years or more in custody? How does a democracy reconcile expansive conspiracy charges with the presumption of innocence? If bail is indeed the rule, why does it remain so elusive in cases involving stringent laws?

For Dr Ilyas, the questions are inseparable from his son’s absence at home. For Mujtaba, they speak to the character of institutions under strain. For the families and former prisoners in attendance, they are lived realities measured not in legal principles but in years.

As the lights dimmed and the hall slowly emptied, the opening line of the evening seemed to echo once more in the minds of many present. Bail is the rule, jail the exception. In that crowded room in Mumbai, the principle felt less like settled law and more like a promise still waiting to be fulfilled.