On some cold mornings, Ajay Negi (name changed) can still taste the acrid, blue liquid spreading down his throat, penetrating his gut, searing them as it travelled down.

It was the winter of 2016. Negi was just 16 at the time. Born and raised in a small town in Uttar Pradesh (UP), Negi had recently relocated to Kolkata with his parents in the middle of a school year.

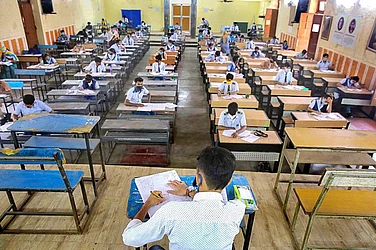

“I had my board exams that year so the pressure was high. On top of that, I faced a total culture shock in the city,” Negi states. He recalls classmates making fun of his ‘Bihari’ accent, though he was from UP and of them ganging up at lunch time to haze him.

“I came from a small town, but they called me ‘villager’. My confidence suffered, so did my academics. I performed poorly in the pre-boards,” he recalls.

Negi’s parents—both employed at the time—were good to him, he says. They worked hard to give him a good life. He didn’t want to disappoint them. Soon after his pre-boards, Negi who was still struggling to cope with the torment at school, decided to swallow some disinfectant he found at home to put an end to it.

Looking back, Negi, now a mechanical engineering student at a city college, felt deep shame at not being able to cope with the pressure of his new reality.

“I had been feeling extremely depressed and alienated from my reality… I did not want to be laughed at,” he states.

Negi’s parents had found him unconscious in the bathroom of their two-bedroom apartment in Kolkata and immediately took him to a private hospital where his father pulled some strings to dodge a First Information Report. Suicide was a punishable offence in India till 2017. Those who survived the attempt to kill themselves were punishable by law.

“It’s such a paradox,” Negi laughs. “On the one hand, they want us to not die. If we die, we get sympathy and even respect. But if we survive, they punish us for trying and ostracise us from society,” he states. To this day, the suicide attempt remains a hushed matter in the Negi household. His parents pretend it never happened.

But not talking about suicide, cannot simply wish it away.

In fact, suicide rates have been rising in India, with 1,64,033 Indians dying by suicide in 2021, resulting in a national suicide rate of 12 (calculated per hundred thousand or per lakh population), the highest since 1967.

The Mental Healthcare Act of 2018 decriminalised “attempted suicide” as a punishable offense under Section 309 of the Indian Penal Code, creating a significant exception. Section 115 of the Mental Health Act assumes that anyone attempting suicide is under stress and in need of support, treatment, rehabilitation, etc. While it doesn’t entirely replace Section 309, it mitigates its impact.

Moreover, even with the altered legal implications regarding suicide, the Act remains highly stigmatised and misunderstood, meaning those who survive often suffer ignominious lives.

The situation worsens for men, constrained by traditional gender roles and hetero-machismo. Failing to conform to these roles results in social sanctions, bullying and a sense of worthlessness.

The ‘Burden’ of Manhood

International suicide data shows that suicides are higher among men. While more women exhibit suicidal behaviour, ideate or attempt suicide, more men die by suicide every year. Various studies have tried to address this gap via sociological, economic, psychological and physiological analyses. But experts believe that the perceived notions of “masculinity” have a tendency to impact suicidal behaviour.

“Masculinity plays a role in male suicides in multiple ways, for e.g., as a barrier to acknowledgement of mental health problems and help-seeking, as well as unique stressors related to being the bread-winner and the higher propensity for alcohol abuse, a key risk factor for suicide,” states Dr Basudeb Das, a clinical psychiatrist with the Central Institute of Psychiatry in Jharkhand.

Das refers to a 2016 neurological study which revealed four traits ‘fearlessness of death, pain tolerance, emotional stoicism and sensation-seeking’ defined as “the acquired capability for suicide” which more men possess, than women. Those contemplating suicide typically overcome their fear of death and build the pain tolerance required for a lethal attempt.

Another research conducted in Oxford, England which studied 4,415 hospitalised patients concluded, that men reported significantly higher levels of suicidal intent than women, following a self-harm episode.

Das states that the gender conditioning of men starts early. “We tell boys that ‘boys don’t cry’. We condition boys from a very young age to not express emotion, because to express emotion is to be ‘weak’. But men may be less likely to admit when they feel vulnerable, whether to themselves, friends, or a general practitioner,” he states.

“For the average middle-class married man, the idea of masculinity is to earn and provide for the family. Failure to do so is seen as ‘emasculating’. Which is why, so many men were committing suicide during the Covid-19 pandemic when unemployment was rampant,” states Kolkata-based author and Professor of English Asijit Datta.

“When we talk about the freedom to work, we also talk about the freedom to choose to not work. Men are usually denied that option. If a man can’t earn or provide for family anymore, his masculinity is challenged. His role and position in the society and household are challenged,” Datta argues.

Between God, the State and the Body

Apart from masculinity, religion also influences attitudes and perceptions of suicide and plays a key role in construction of masculinities across cultures. Religious notions are central to a society’s cultural and legal perceptions towards most things concerning life and death and often lead to conflicting opinions on what is permissible, in life as well as death (or afterlife for those who believe in it) Dante Alighieri’s Inferno, designates the severest rung of Christian hell for suicides. In Christianity, the human body is considered a sacred temple, inviolable unless by divine will. Eurocentric, Victorian-era beliefs have also impacted contemporary suicide laws globally.

In contrast, many Eastern philosophies and religions view the body as transient and materialistic. Hindu philosophy, for instance, sees the body as perishable, with the indestructible soul undergoing rebirth. According to Somparn Promta and Prakarn Thomyangkoon’s paper, ‘A Buddhist Perspective on Suicide: The Past, the Present, and the Future,’ all Buddhist sects share the belief that death is a transformation of life, and life is a cycle of living and dying, distinct from religions without belief in reincarnation or life after death.

The laws around suicide centre around the right to live, what but about the right to die? In Jainism, the practice of “Sallekhana”, known variously as Santhara, samadhi marana, etc, is a vow taken at the end of one’s life willingly by slowly reducing or entirely stopping food intake. Though Jain scholars and philosophers don’t categorise it as “suicide,” this practice has sparked debates around the right to life versus the right to die, frequently invoked by pro-euthanasia advocates.

Suicide typically stems from the pain of unfulfillment or protest against worldly failures according to author and Indian Police Service officer Vipul Anekant, sentiments which he says, differ from the objective of the Santhara practice.

“Santhara represents a break from worldly want and need as well as from the power schematics that govern our body,” says Anekant.

These beliefs are protected in India by the Right to Freedom of Religion. In 2015, the Rajasthan High Court banned the practice, bracketing it as suicide, but the verdict was stayed next year by the Supreme Court of India, which lifted the ban.

Historically, the political state has attempted various intrusions into the personal realm of the body.

Datta highlights that even in the diluted Section 309, individuals retain some rights to their bodies, although the state claims ownership rather than the individual. Birth and death, both subject to state regulation, remain beyond individual control. He believes that “Section 309 implies that only the state has the authority to legally take a life and exerts control over the body in other ways as well.”

“There is something a little fascist in not allowing a person to exert control over their own bodies unless it’s sponsored by the state. Martyrs are not considered as having died by suicide, even though they wilfully go into battle. Jawans are not seen as suicidal but rather, dutiful and brave,” says Asijit Datta.

Today, much of high-pitched nationalism promoted by the state or its forces requires a blood allegiance. Beyond the army, even members of certain majoritarian civil society outfits claim to be ready to give their life for the nation. Or take the lives of others. This holds true especially for religious or nationalistic politicisation that thrives on weaponising identity and mental health crises, especially among men.

But Dr. Basudeb Das is against pigeonholing suicide solely as a “male problem”.

“Issues of male suicides and female suicides are mutually exclusive and in terms of policy recommendations, there is absolutely no need to pit one against the other, which is currently the dominant discourse,” he states.

Meanwhile, Negi who survived his own suicide, never went to therapy or received any counselling per se. He does not feel suicidal anymore and tries not to think about it. “I think I am stronger now and know how to cope with alienation,” he states.

Is he happy though? He shrugs when asked. “I don’t know, I am alive. That’s enough, for now”.

(This appeared in the print as 'The Sting Of Stigma')