When it comes to property inheritance rights, India abandons all pretence of equality or secularism; ossified social practices embedded in patriarchal religious customs take over. Independent India began with property inheritance laws that were biased towards men, even though India was one of the first countries to give voting rights to women.

Women were typically bid farewell during their weddings with ‘streedhan’ (a trousseau of clothes and, mainly, jewellery), which was mostly controlled by her husband. And in recent decades, various property rights laws did not give them control over their own property. This is despite Article 14 of the Constitution of India, which broadly recognised all individuals (including non-citizens) as equal without discrimination on any grounds, including gender. It has been argued that a reason for this could be reading property rights from orthodox religious views, be it Hindu, Muslim or Christian.

The ruling Congress party was divided over introducing property inheritance for Hindu (which includes Sikhs, Buddhists and Jains) women. Women could not have any share in the joint (Hindu Undivided) family property as per orthodox Hindu customs. That is why they could not become a ‘karta’ (patriarch) of the HUF. Whatever rights accrued to women under the 1956 Hindu Succession Act were also patriarchy-driven.

Before it was passed, so strong was the opposition to reforming property laws in favour of women that there was an All India Anti-Hindu Code Convention backed by the RSS, Jana Sangh and Hindu Mahasabha against the proposed ‘Hindu Code’. Earlier, B.R. Ambedkar had resigned as the first Union law minister in 1951 in protest against Parliament stalling a vote on his draft of the Hindu Code Bill.

Changes began from South Indian states during the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s, creating rights for Hindu women. A contemporary version of the reforms were worked into the 2005 amendments to Hindu succession laws, including a share in the father’s property even after marriage. Yet, some regressive loopholes still remain in the new law.

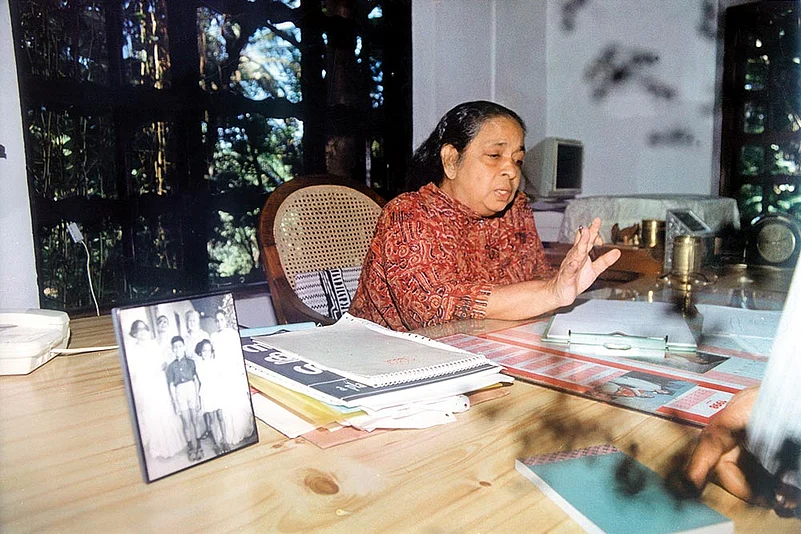

Renowned women’s rights advocate Flavia Agnes has noted that the situation has been graver for Christian and Muslim women. Technically, a parent can grant a share in property to a Christian or Muslim woman through a will. Muslims are limited to sharing one-third property by will.

Most deaths are intestate (without a will of the deceased) and in that case, customary law applies, which does not accord both genders equal shares. If there is a will, a woman gets only a half of what the brother is entitled to in Muslim law. The recent hearings against the triple talaq system exposed how prejudiced the interpretation of religious custom was against women.

It is not just a matter of what the religious code does or does not dictate directly; social attitudes coloured by religion, largely patriarchal, also keep women dependent on the dominant male of the family. All this hinder economic liberalisation of women.

There is no empirical evidence to prove that the 2005 amendments to Hindu Succession Act created a difference. Instead, studies have shown that women often give up asserting these rights in favour of “maintaining familial harmony”. Yet another study found that women who do inherit property do not have physical possession of land deeds, which are in the custody of brothers, husbands and the dominant male. Clearly, enlightened laws can only go so far.