The recommendations made in the Model Prison Manual (MPM 2016) aim to address high suicide rates and the prevalence of mental illness among prisoners

The MPM also specifies a benchmark for doctor-to-prisoner ratios, requiring at least one doctor for every 300 inmates

As these reports gain dust, it is important to look deeper into the malady that the broken prison system of India embodies

I had trouble in my barrack with some of the inmates smoking heavily beside me and some among them playing ludo till the wee hours. As the game intensifies with gambling, so does smoking and use of tobacco. I requested the officer-in-charge of my circle to intervene.

The main culprits involved in the matter were dear to the officer. The first one belonged to his own community (caste); used to pay for privileges,along with also passing information about the barrack. The second one used to collect money on his behalf from well-off inmates in need of privileges or from such newcomers who are marked off for their rich background (offence-wise or family background). So, to expect the officer to act decisively and impartially would be wishful thinking!

I’d have usually avoided such a situation trying to convince the inmates to be considerate. But this time, it seemed more deliberate and perhaps with blessings of the officer himself! It didn’t take long for the officer to defend his men. As long as cigarettes and beedi are available in the prison canteen, the inmates are free to smoke anywhere, anytime, he said. Why outside the prison were people fined for smoking in public places though cigarettes are available everywhere was met with a frown. As the inmates are stressed out, they can/may play till late into the night or early morning. That others who are struggling to get some sleep can also get stressed was of little concern for him!

While making all efforts to belittle my concerns, the officer was careful to make an offer which I found difficult to refuse, given his indifferent attitude to my difficulties, which, in his universe, where everything had a price was of no consequence and to his chagrin, he couldn’t get anything from me! He suggested I shift to any barrack of my choice with the place I would want to sleep (the sought after “upar ki patta”, topmost part of the barrack) and enough place to keep my belongings (books galore).

In the new barrack, Nitin, who was sleeping beside, introduced me to Sanjay who shared the space after him: fair complexioned, bearded, a recluse, who talked very little in an otherwise noisy barrack. I’m considered as a very accessible person in the circle. People come from other barracks, too, to get their applications written, some out of curiosity to know about our case and others to take opinion on their chargesheet or looking for the possibility of an honest, affordable lawyer. There were quite a few who wanted to talk about the mistreatment that they endured from the prison officials, be it in the prison hospital or the judicial section from where court productions were done. There were some who wanted to frame the right questions in their RTI applications that they wanted to file against the prison officials or to get valuable information from the police stations where their FIR was filed or to the hospitals where some medical records of significance can be obtained. But Sanjay, two months into the prison, kept a studied distance though being two feet away from me. I thought, it might be due to my case and the perceived ‘awe’ it carried. But I was wrong. He slept very little, or one may say, he didn’t, often staring blankly, totally lost. You find him stretching, doing push-ups, fixing his biceps and shoulders morning and evening. He seemed to be under tremendous stress, accused of murder of his wife suspecting her fidelity and survived by two children, a girl and a boy.

Twenty days might have passed. It was quarter to seven, early morning, after the bandi opening. Nitin hurriedly came, dazed, gasping for breath and told me that Sanjay had jumped over the stairway banister from the first floor to kill himself and he was carried on a stretcher to the prison hospital.

The stairways in the circles in Taloja Central Prison are perilously narrow and steep with short concrete banisters where if you lose your feet can easily tumble over. In the rains, it is most dangerous as the roofs leak (Taloja Central Prison is a monument of corruption) and the steps get slippery. Imagine a situation where you have already lost your marbles, and your feet?

Rumours abounded about Sanjay’s health in the prison hospital. After two days, we were visited upon by the sad news of his death. There was no announcement of the death of Sanjay nor any efforts to address the elephant in the room: increasing instances of deteriorating mental health of the prisoners.

Taloja Central Prison is a correctional facility. It implies the prison administration be fundamentally informed of the centrality of a reformative approach to the everyday life of the prisoner in confinement. This necessitates among other things, the presence of such trained personnel (counsellors) inside the prison to facilitate lively interaction with the everyday experience of the prisoner. Taloja, which averages around 3,500 inmates, has one psychiatrist visiting the prison every fortnight for a few hours. It is not an easy task to get an appointment with the psychiatrist. Even if one makes it, there is hardly any counselling. One gets treated on the symptoms rather than based on a thorough investigation followed by counselling on the problems confronting the prisoner.

After a few perfunctory questions, if the doctor deems the prisoner a mental health case, heavy doses of powerful psychiatric drugs(antipsychotics, antidepressants, mood stabilisers and anti-convulsants, anxiolytics and sedatives) that numb your senses and put you to sleep are administered with more emphasis on medicine-oriented prognosis than counselling or any genuine attempt to understand the specific issues on a case-to-case basis. These drugs are much sought after by drug addicts, and gangsters in the prison to maintain their wards. Invariably, most of the recipients of such drugs sell it off for buying their canteen essentials or for a pack of cigarettes or to buy chicken curry served in the wet canteen twice a week.

Into a week after the death of Sanjay, a three-star officer (senior PI) from the Kharghar police station made a quick visit of our barrack with the senior jailor and the circle officer in tow. It was clear that he was going through the formalities of an investigation. Nitin’s statement was taken as he and Sanjay used to eat together and also share the stuff that they bought from the canteen. The body of the deceased was later handed over to his family. The only response from the prison administration was to erect an iron mesh in all circles with one end drilled into the banister and the other on the wall overlooking the ground floor and stairway.

Within a fortnight, as the tyranny of the routine took over, everyone got busy in their world of endless repetition, solitude and boredom. Those who could afford to access legal defence would fret about the delay in the proceedings in the higher courts. Often suspecting/questioning the reliability of their legal counsel. Of the few whose trial has commenced, worries abound about their lack of production in courts. Those being produced on video-conference are unable to comprehend what is transpiring in the court, not to say their lawyer’s inability to communicate with them. It is in the repeated performativity of the above that life in prison oscillates between despair and hope.

As usual, like in many other arenas of policy making, some of the best reports have been written (based on the direction of the government of the day) calling for prison reforms. The most recent being the Model Prison Manual (MPM 2016). To our specific case, the suggested standard for mental health professionals in prisons is 1 for every 500 inmates. Though a far cry from healthy standards, when compared to the present ratio in prisons in India, which is one for every 23,000 prisoners, it is far more commendable. These recommendations aim to address high suicide rates and the prevalence of mental illness, estimated to affect 1.6 per cent to 33 per cent of the prison population. Moreover, the MPM also specifies a benchmark for doctor-to-prisoner ratios, requiring at least one doctor for every 300 inmates. As these reports gain dust, it is important to look deeper into the malady that the broken prison system of India embodies.

The prison system in India, persistently mediated and nourished by its colonial and retributive sensibilities, cannot be wished away by just changing the names of the prisons as correctional facilities. The reformation of the prisoner cannot be realised in isolation as prisons are a microcosm of our society. Even if the prisoner makes an attempt to change, s/he goes back to the same society which produces and reproduces the objective and subjective conditions that violently left her/him out in the margins bound by the weight of its repressive, exploitative and discriminating hierarchies. Our prison continues to remain broken as it helps in reinforcing the society it inhabits.

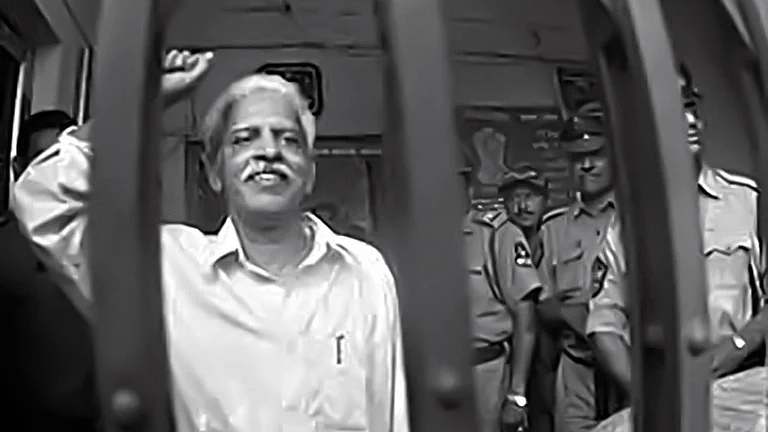

Violence erupted on January 1, 2018, during a Dalit commemoration of the Battle of Bhima Koregaon’s 200th anniversary, resulting in one death and multiple injuries from stone-pelting and arson. Tensions stemmed from caste hostilities, with the speakers at the Elgar Parishad event probed for incitement. Investigators named several activists in connection with the Elgar Parishad event. The celebration commemorates the 1818 battle, seen as a symbol of Dalit resistance. Key arrests included Sudhir Dhawale and Jyoti Jagtap, followed by activists such as Surendra Gadling, Shoma Sen, Mahesh Raut, Rona Wilson, Sudha Bharadwaj, Arun Ferreira, Vernon Gonsalves, Varavara Rao and Gautam Navlakha.