Avantika Mehta speaks with Saurabh Bhattacharjee, Associate Professor at the National Law School (NLU) and also a co-director for the Centre of Labour Studies.

Are labour laws as they presently stand able to withstand the advent of AI, and potential loss of global labour income and jobs for human labourers?

At a fundamental level, most of our existing labour legislations were built around this Fordian model of production and never contemplated the sort of systemic change that AI will bring in; so it requires significant overhaul, which the [new] labour code has not done. The labour code largely sticks with the current model of regulation. That's one caveat that any scholar or policy maker has to keep in mind: our existing paradigms were not even built around such forms of technology.

But having said that, on the question of loss of livelihood because of AI, that in many ways ties up with the effect of automation on jobs and that would require much stronger social security, protection for workers who lose their jobs as a result of such transformation. This could be some sort of unemployment or social security allowances so we, in fact, have something the Employees State Insurance Act, something very basic as a form of unemployment insurance which is the traditional model that ILO had followed that we need to have some security around income loss, and one of the forms of income insecurity is unemployment.

And if employment is going to become more of an exception, and more of the work is getting shifted to automated instruments either through machines or AI, we need to really strengthen our existing unemployment allowances. India in fact has something very rudimentary in comparison other Western countries. Having said that, the other model is the Universal Basic Income, and in fact, one of the major drivers around UBI has been that we are entering an era where there would be mass layoffs because of automation and we need to think in terms of basic income and your subsistence is coming from your employment. That's the other debate, there were a few reflections by the Economic Advisor on the ways to fund UBI.

We strengthen social security protection and move towards a UBI, although that brings in separate challenges.

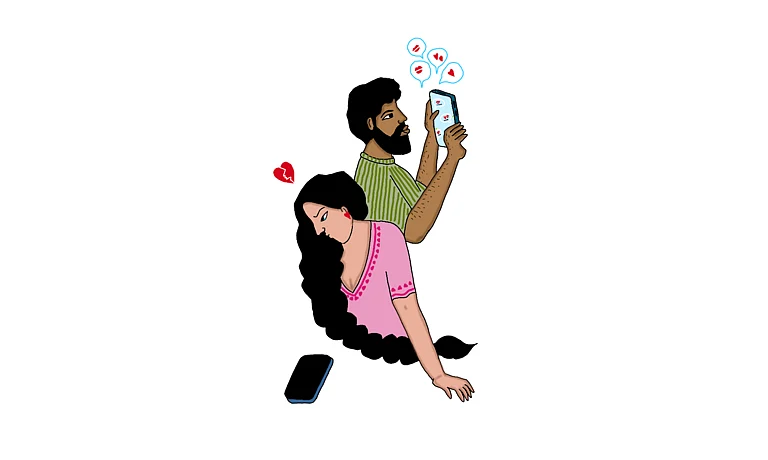

Studies show that AI adversely affects minorities—including gender minorities. What laws and policies could help protect them against being disproportionately impacted?

In social security protection itself we need to think of particular forms of vulnerability, whether it's on account of gender or on account of caste/ race etc that must brought into the social security administration. That's something we have to think about because we can't have a generic response because we have to understand not just the loss of jobs, but algorithm's work itself leads to severe forms of discrimination. And some scholars have also pointed out that discrimination that gets further sanctified through how algorithmic software works. So gender will certainly be one part of the safeguards that we bring in place.

With AI and automation being integrated into the workplace across industries, what sort of accountability and transparency would be possible where AI is given managerial work?

That's where a huge amount of work needs to be done, both in social security and in terms of grievance redressal, what kind of transparency we have on AI-based decision-making. In fact, one of the ILO papers says that just looking at UBI would not be sufficient, we need to link human rights and labour together, and think of structural changes and think about how use of AI is subject to control that we use in labour laws-- so how would trade union and collective bargaining work in a situation where we are handing over decision-making to AI. In terms of managerial decision-making, so far we believe there have to be safe-guards against arbitrary decision-making but where these decisions are being made by an algorithm that we don't fully understand, what would be the standards of arbitrary termination, what would be the standards of victimisation: these we'll have to think of.

Are there any international laws that India would also be helpful in the Indian context?

If you look at the EU laws, there have been two examples that perhaps India needs to look very closely at:

1) The directive on platform work: has provisions on algorithm transparency, and the right to human interface. And the Karnataka platform work bill also touches upon that, albeit in a very soft way. It seems our platform aggregators have a problem with even that soft reference. That's one where we clearly ensure that there's a defined human interface and some modicum of transparency.

2) The EU's AI Act: where they've barred some forms of decision-making and also barred certain factor that AI can take into account that are seen as excessively intrusive and invasive of human dignity. I think we also have to look at similar provisions. In the past, we spoke about abolishing bonded labour; if we spoke prohibiting forced labour on the grounds that this is commodification of human being and that is so exploitative and abhorrent that we cannot have such practices, and I think similar regulations must be designed in terms of what kind of information AI platforms can use and what kind of factors could be taken into account and something invasive like facial recognition we'll have to have safeguards. What those safeguards will be, we don't know yet--perhaps we'll take the EU model, perhaps those who work on AI and technology would understand much better than me, But I think that's something we'll think about: do we leave everything for platform AI decision-making, or will there be some safeguards and I see parallels with the debate around cloning and other questions. We'll have to draw up on some of that reflection that happened around cloning.

Reports suggest that the service sector such as customer services would be highly affected by AI adoption? Would you agree?

Our service sector would be impacted by AI, and we cannot pretend it would not affect us in a major way. The argument is that in response there may be other jobs created so that might justify the optimistic line of view.

But we saw this already in the West: where the new jobs that were created by globalisation and out-sourcing were largely high-skill work, and the lower-wage workers did not find any equivalent new jobs, and I think something similar will happen in India, and we need to be worried about this.

I cannot help but notice that India, in particular, has not even begun thinking of any of the sort of policies and safeguards that you are suggesting. What would be the outcome if we are wait further to put policies in place?

Partly the government hasn't brought up any of these is because of regulatory capture that happened where a lot of this regulation is being driven by our IT companies or our platform companies rather than a more democratic consultative process. We are certainly far off, and even the limited attempts that have been made around labour regulation and platform work, even there we are not talking about algorithmic control and the ethical questions that algorithms raise. We are just talking about recognition of some basic labour rights at the workplace for them, so we certainly need to foreground this in our public discourse, which hasn't happened at this moment.

Historically, one might say that law has always caught up with technology and followed technological growth and then tried to make sense of regulatory challenges, so perhaps, even here, it will not be much of an exception. But on the other hand, the concerns that will come up with is that if the basic regulatory framework is not put in place too early then we will have regulatory capture, and the regulations will be framed by major IT behemoths and other companies which have a vested interest and that may militate against any form of transparent, consultative regulation on this, and that would be a tragedy for us: we are already seeing this in pharmaceuticals, we are seeing with several other fields. And we don't want that to happen to use of AI itself.

To look at data on India: I think there is a gap in our knowledge in this question in terms of what has been the existing impact of AI in India. We need to look at literature around that. I don't know of anyone doing anything like that; I've not come across too many Indian works on this.