Bollywood has been in decline over the past few years—as evidenced by the gradual departure of major stars from the exhibition space. The pandemic has been blamed but there is apparently a deeper malaise; the unprecedented success of South Indian films or remakes, beginning with Kabir Singh (2019) should have told us that. But now, with the thumping successes of RRR and KGF 2, the writing on the wall is clearer that Bollywood is arguably on its last legs. The success of The Kashmir Files, rather than allay this suspicion, only strengthens it, if one reads the symptoms right.

If one studies the distribution of male stardom at any time in Hindi cinema after 1947, one sees that three or four stars have dominated at each moment, and each one has carried forward a concern identifiable as a ‘narrative of the nation’. India being a patriarchal society, films dominated by the heroine (Andaz, 1949) are specifically about gender issues and the condition of women—as ‘women’, rather than as mothers or sweethearts. This is unlike Hollywood, where a woman can be placed randomly in a masculine situation. The muscular women in the 1930s and 1940s meant something specific here. The vigilante in Hunterwali (1935), for instance, signalled the weak man and appeared alongside the first Devdas (1935). It went along with a crisis of masculinity in the colonial era duly noted by social scientists like Ashis Nandy.

The leading male hero in the early 1950s were Dilip Kumar, who through his ‘method’ performances (Babul, 1950) articulated the uncertainties of the young nation; Raj Kapoor, on whom rode egalitarian impulses (Awaara, 1951); and Dev Anand who problematised the issue of the ‘modern’ (Baazi, 1951). There are multiple narratives at any one time, as the nation is a complex proposition with many issues confronting it. Mother India (1956), for instance, addressed the issue of agrarian unrest—covertly pointing at Telangana—and held up the rebel’s punishment as fitting.

Hindi cinema was Catholic since it needed to address a vast populace across the nation, while regional cinema that addressed local identities could become more pungent. Regional cinema could also afford a dominant male hero (NTR, Rajkumar, Uttam Kumar, MGR) who appeared in several narratives concurrently and hence played a variety of roles. Dubbing a regional film into Hindi could also change a film’s purport as in Mani Ratnam’s Roja (1992). In that film, the wife collars a Hindi-speaking soldier and screams at him in Tamil when her husband is kidnapped; the film is playing the regional language card, which dissolves when the film is dubbed into Hindi. Regional films generally speak in two voices, one emphasising the separateness of the local and the other valourising national goals and values.

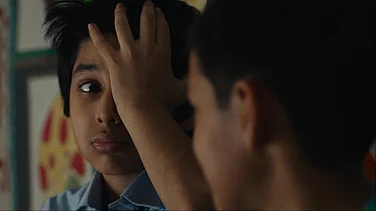

The phenomenal success of South Indian films in spaces traditionally given to Bollywood has come alongside the success of a new kind of Hindi cinema not in evidence earlier, viz.: the propaganda film. The term ‘patriotic’ is used to describe The Ghazi Attack (2017) and Uri: The Surgical Strike (2019) but they are not from the same mold as Manoj Kumar’s Upkar (1967). A key difference is that the earlier film invoked the family life of the soldier in some way and suggested that war was only one activity that the nation was engaged in, and that other things would also be happening like agriculture. The new films are single-minded in suggesting that military duty prevails over everything else. Upkar had Indian villains engaged in hoarding and black-marketing while the propaganda film only has Pakistanis as villains. By this definition The Kashmir Files is a propaganda film: it is not a sensitive human drama about the ‘ethnic cleansing’ of Kashmiri Pandits but about patriotic Hindus brutally targeted by pro-Pakistani Kashmiri Muslims. In the very first scene a Pandit boy is pursued by hostile Muslims for cheering Sachin Tendulkar, who has just helped India win a match against Pakistan.

Considering the successful South-Indian films and their content, the unkempt facial hair of the hero virtually defines him in KGF 2 and that is also true of Pushpa: The Rise (2021). We also recollect that unkempt facial hair of the protagonist in Arjun Reddy/Kabir Singh connoted resistance to authority. On studying the other dramatis personae in these films we also find that those representing authority in KGF 2 and Pushpa are well-groomed. In RRR, the anti-British rebel played by NTR Jr has an unruly beard and his associate played by Ram Charan is well-groomed when serving the British, but with a rough beard when he changes sides.

ALSO READ: OTTs Are The New Mainstream, Here's How

As regards their enemies, in Pushpa and KGF 2, those who wield authority politically or as representatives of the state are well-groomed. In both these films, an association is made between criminal bosses and officialdom, and the protagonist is a self-made man with a following of helpless people; Rocky in KGF 2 even stands up to the Prime Minister who is a ‘dictator’. In each of these films, the conflict is consistently between the local hero and central authority. In Pushpa, the Telugu protagonist meets a brutal police official (IPS) named Bhanwar Singh Shekhawat and humbles him. In Drishyam (2015), the male protagonist is trying to protect his family from the police. RRR pretends to be ‘anti-British’, but is unable to make credible hate figures out of them. It focusses on the prowess of the local hero, with the British only as a pretext. The names given to the protagonists are those of tribal leaders fighting for local causes and not part of the national struggle led by mainstream political parties.

The corrupt/brutal servant of the law is not a new motif in Indian cinema and went hand-in-hand with a sense of the weakening state, but the state was usually distinct from the nation. In the sports films of the last decade, like Paan Singh Tomar (2010), the protagonist loves the nation but hates officialdom. It was as if the patriotic Indian needed to connect directly with the nation without the mediation of the corrupt State. The new South Indian films target the State as represented by the police with renewed vigour, but there is no corresponding eulogy of the nation; and the criminals do not transform. The criminal hero may not be allowed to harm policemen, but with the brutal/corrupt conduct attributed to the latter, there is no doubt that the audience is with the lawbreaker against State authority.

I propose here that the decline of Bollywood—as implied by the weakening male star presence—happened at around the same time as the rise of Hindu nationalism as a sentiment in the public space. The following conclusion may be speculative, but the growing strength of jingoistic patriotism could have depleted the other narratives of the nation, in effect leaving no spaces for major Bollywood stars to explore, nor for possible roles to enact. Salman Khan’s popularity seemed to have survived longer, but his last film Radhe (2021)—in which he played a heroic policeman—is seen to have flopped. If recent regional South Indian cinema is any indication, it is taking a diametrically opposite position from Bollywood. It is dealing predominantly with social divisions (as in Jai Bhim, 2021) while Bollywood is being persuaded to eulogise national unity; and the signs are that the ‘divisions’ have the upper hand.

There is a large enough public favouring nationalist sentiments to keep propaganda films going as a successful enterprise—since The Kashmir Files was also phenomenally successful. But I believe that more thematic variety is available outside the narrow realm of patriotic discourse. If Bollywood is to survive as a cultural force, the only viable option available to it may be to stop being a national cinema and go ‘regional’, become pungently provocative as regional films are, although tentatively on smaller budgets. But the important thing would be to resist the temptation to be ‘national’ in its address and scope, which now seems to mean repeating, unthinkingly, the political rhetoric in the public space.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Phenomenon of Patriotism")

(Views expressed are personal)

ALSO READ

M.K. Raghavendra is a National Award-winning film critic and author