The interim government’s order to enforce the July Charter—despite broad political support—has raised serious questions about its constitutionality and the legality of the proposed referendum.

The four referendum questions must be accepted or rejected as a whole, limiting voter choice and ignoring dissenting positions from parties that opposed certain institutional reforms such as the formation of constitutional bodies and a bicameral parliament.

Although most parties, including the BNP, have welcomed the implementation plan, unresolved constitutional ambiguities and procedural concerns threaten to create prolonged instability at a time when Bangladesh can least afford it.

For the observers of Dhaka’s politics, the chief adviser’s order regarding the implementation of the much-publicised July Charter is seen as a welcome step, after weeks of uncertainty. The charter sets out a reform package backed by most major political actors, except the Awami League, the party of deposed authoritarian leader Sheikh Hasina, despite some reservations among other parties. Yet its implementation could still prove explosive, raising more questions than answers.

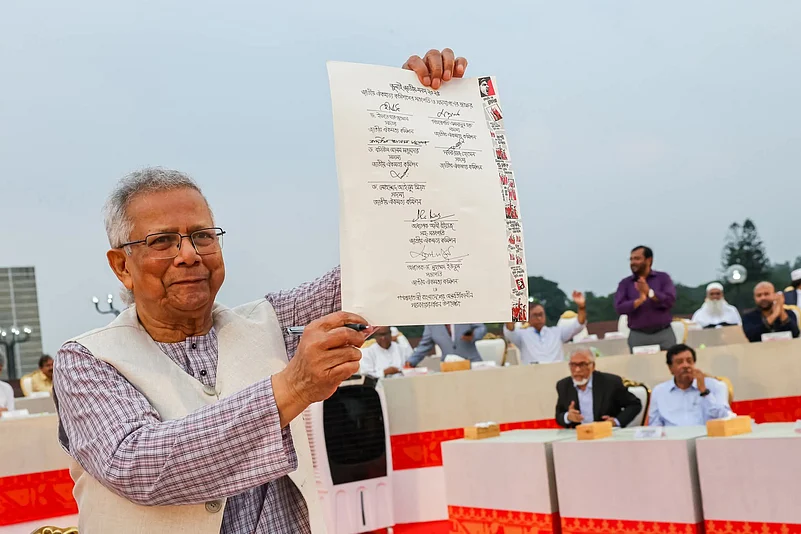

The technocratic interim government formed after Sheikh Hasina’s fall in early August 2024, led by Nobel Peace Prize laureate Muhammad Yunus, aims to repair the institutions that enabled her increasingly authoritarian, “fascist”, in the words of Professor Ali Riaz, rule. It established several reform commissions to propose changes to key institutions and to the constitution.

The decision to create these commissions was welcomed by all major parties, including the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP). Indeed, the establishment of such bodies was central to the BNP’s widely discussed 31-point programme. In its first 15 points, the BNP called for commissions on constitutional, administrative, judicial, media and economic reform, each expected to report within a set timeframe to enable swift implementation. The interim government has essentially done this work for them.

However, when the proposals from the commissions were revealed, they appeared more like a utopian vision than practical solutions. In response to the growing debates, a National Consensus Commission was established, with the Chief Adviser serving as its leader and Professor Ali Riaz as his deputy. Negotiations took place between parties with little to no experience in managing any public office, let alone the country’s complex bureaucracy, and the BNP, a party that had governed for fifteen years since 1978. This collaborative effort helped the commission understand the realities on the ground, leading to significant modifications of many of its initial proposals to better align with the country’s context.

Some imprudent proposals persisted because of the Commission’s insistence, which appeared to be colluding with certain political groups. The BNP expressed their dissent, fearing that these proposals might lead to instability. Their concerns were acknowledged in the July Charter, which was signed in mid-October, as the Charter included a provision stating that any party disagreeing with a particular proposal would have the right to act based on its stance, provided it had secured the mandate of the people through elections and had explicitly mentioned its plan on that issue in its manifesto.

As the Chief Adviser announced a special order for implementing the July charter, concerns have been raised from various fronts—some publicly and some in private discussions.

The first concern on the list involves the legality of the order. Citing Article 93 of the Constitution, which effectively restricts the President from altering the Constitution, eminent lawyer Barrister Shahdeen Malik opined that the provisions in the order, which later became a gazette, may create constitutional complications and can be deemed unconstitutional since the gazette proposes several provisions to be taken to a referendum that are contrary to the Constitution, since the Constitution has been in effect and was not suspended after August 5th 2024. The concern was also raised by the “blue-eyed boys” of the government, who formed the new political front, NCP, which has been against the idea of the President signing the gazette.

The next question is about the proposed referendum’s legality. After the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which annulled the provision for holding a referendum by amending an article, the country lacks the legal basis to hold a referendum to amend the Constitution. Although a court in Dhaka reinstated the provision, the decision is still pending review by the appellate division. It is currently unclear in which constitutional framework the government can hold the referendum.

Another major concern regarding the referendum is the nature of its questions and how they will be answered. The Chief Adviser has outlined four questions on the ballot, seeking consent for the formation of an election-time caretaker government and constitutional institutions based on the July charter, the introduction of a bicameral parliament with 100 members elected by party vote proportion, and whether the next government should implement 30 agreed-upon proposals and other relevant ones from the Charter. Voters must either agree to all four questions or none at all, limiting their ability to express their preferences on each question.

This attempt to steer public opinion reveals an elitist attitude among a small group of ‘intellectuals’ intent on imposing their preferred reform package, convinced they know best. The questions raised also disregard the objections submitted by parties that opposed proposals on forming constitutional bodies and creating an upper house, even though the July Charter allowed dissenting parties to pursue their own plans after the election, provided these were clearly stated in their manifestos.

Despite these concerns, most political parties seem to have accepted the interim government’s implementation plan, with the BNP welcoming the move. Yet if doubts over the referendum and the July Charter persist, they risk plunging the country into prolonged instability, something Bangladesh can ill afford.

The author, A K M Wahiduzzaman, is the Information and Technology Affairs Secretary of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party-BNP.