Delhi’s annual winter smog, once seen as a seasonal inconvenience, is now assuming the proportions of a slow-moving public health emergency, say doctors who witness its toll unfold in hospital wards every day. What they see, they warn, is no longer limited to worsening of pre-existing disease but an unsettling rise in new patients—previously healthy individuals now reporting breathlessness, persistent cough, inflamed airways and unexplained fatigue.

“As doctors treating the fallout of toxic air year after year, we know how deeply it is scarring public health. It is a sort of medical emergency, I would say not only as a medico but also as a resident of this city,” said Dr. Anant Mohan, Head of Pulmonology and Critical Care at AIIMS Delhi, cautioning that “all is not well” with the Capital’s air.

Dr. Mohan underlined a growing concern in global research — that ultra-fine pollutants are crossing the placenta and reaching the fetus. “Babies exposed in utero are more likely to be born underweight, with fragile lungs. If we fail to intervene now, the damage will echo across generations,” he warned.

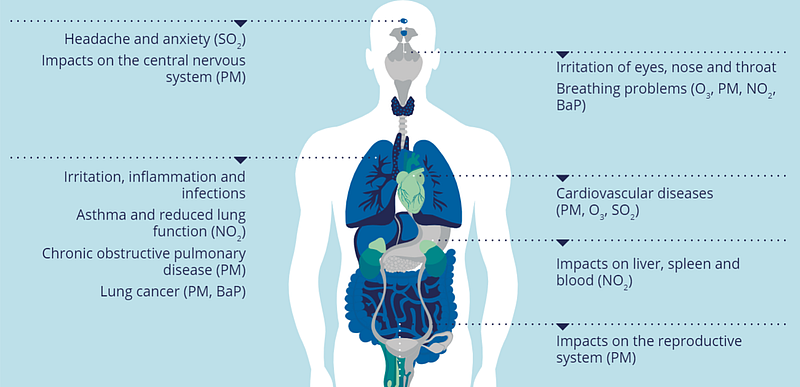

Echoing this, Dr. Saurabh Mittal, Assistant Professor at AIIMS, said that the fallout of prolonged pollution exposure is no longer restricted to cough or mild breathlessness. “We are witnessing an uptick in asthma flare-ups, lung inflammation, COPD, and cardiac complications. These particles enter the bloodstream, increasing risks of heart attacks and strokes.”

The surge is already visible in hospitals across the region. Dr. Vijay Kumar Agarwal, Head of Pulmonology and ICU at Yatharth Super Speciality Hospital, Faridabad, said emergency departments are seeing higher footfall. “We are seeing middle-aged patients with previously mild asthma now requiring nebulization. Geriatric wards are reporting spikes in COPD and heart-failure admissions triggered by high particulate exposure and hypoxia.”

Dr. Agarwal cited the World Health Organization’s classification of PM2.5 as a Group 1 carcinogen — placing it in the same category as tobacco smoke. “Cities like Delhi, Lucknow and Kanpur consistently report PM2.5 levels 10 times above the permissible limit. Even a 10 microgram rise in long-term exposure significantly increases lung cancer risk, even in lifelong non-smokers,” he said, referencing findings published in The Lancet.

A July study in Nature adds a sharper dimension to the concern, offering the strongest genomic evidence yet that polluted air leaves behind DNA damage patterns similar to tobacco exposure. “We’re seeing lung cancer increasingly appear in never-smokers, and our findings show that air pollution is linked to the same kinds of mutations we usually attribute to smoking,” said co-senior author Ludmil Alexandrov of the University of California San Diego.

Dr. Agarwal noted that each escalation in AQI — whether from “moderate” to “poor”, or “very poor” to “severe” — corresponds to a spike in PM₂.₅ and PM₁₀. “These particles travel into the bronchi and alveoli, triggering inflammation and impairing oxygen exchange. For asthma patients, this translates into wheezing and increased reliance on rescue inhalers. Among COPD patients, high particulate loads precipitate acute exacerbations with oxygen dips often requiring hospitalization.”

He advised residents to avoid outdoor exertion once air quality breaches 300, keep windows closed during peak pollution hours, and use certified air purifiers. Vulnerable groups, he said, should maintain a “pollution action plan” — strict adherence to inhalers, monitoring peak-flow readings, and early medical intervention for flare-ups.

Beyond immediate symptoms, the crisis is starkest for those with the fewest resources. Dr. Khyatee, physiotherapist and former AIIMS researcher, stressed that socio-economically disadvantaged communities remain disproportionately exposed. “Many live along busy roads or industrial belts where pollution is consistently higher and access to quality healthcare is limited. Actionable, ground-level plans must be drawn up for them,” she said.

Raising another red flag, Dr. Rahul Sharma, Additional Director – Pulmonology at Fortis Noida, called for mandatory lung screening. “Breathlessness, even occasional, should never be ignored. Spirometry must become part of routine check-ups. Respiratory complaints have risen by 30–40% over the last three months. Many COPD patients have never smoked, proving that pollution, biomass smoke, occupational dust, infections and second-hand smoke are equally harmful.”

A new scientific analysis adds urgency to these warnings. A study in Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety has found that nearly 40% of inhaled PM2.5 in children reaches the deepest regions of the lungs, posing long-term and potentially irreversible harm.

Paediatricians say the findings reflect the surge in children arriving with severe eye infections, breathlessness and persistent cough. The visible symptoms, they warn, may be “just the beginning”, with deeper health impacts likely to surface years down the line.

Environmental pollution’s role extends beyond respiratory stress. A review published in Science Direct last year underscores the growing evidence linking air pollution with kidney disease. The review notes that short-term exposure raises risks of kidney-related hospital admissions and death, particularly among vulnerable populations. Long-term exposure — even at moderately elevated levels — triggers systemic inflammation and oxidative stress, accelerating kidney damage. Pollution also worsens hypertension and diabetes, further advancing renal decline.

As the crisis deepens, doctors across disciplines are unanimous: Delhi can no longer treat pollution as routine.

Several experts reiterated that while short-term advisories are essential, they cannot compensate for the absence of decisive structural interventions. Clinicians argue that emergency measures — including stricter emissions control, industrial audits, real-time enforcement of construction rules, and targeted protection for vulnerable neighbourhoods — are urgently needed.

With evidence now showing impacts stretching from the womb to old age, and from lungs to kidneys, doctors insist that the health emergency must spur swift, coordinated government action to prevent what they describe as “intergenerational harm” to the Capital’s residents.