In mid-November 2018, a Bible-clutching American evangelist trespassed onto the forbidden North Sentinel Island in the Andamans and laid eyes on the “world’s most isolated” indigenous people—the Sentinelese. “My name is John [Chau] ... Jesus Christ gave me the authority to come to you,” he hollered. The Sentinelese, who live in voluntary isolation, repelled him. The evangelist, however, was resolute to “declare Jesus” to the inhabitants of “Satan’s last stronghold.” And the rest is history.

Two decades earlier, another American—a telescope and camera-clutching journalist—had illegally visited North Sentinel and published The Last Island of the Savages (2000), a long-form story that would later inspire Chau.

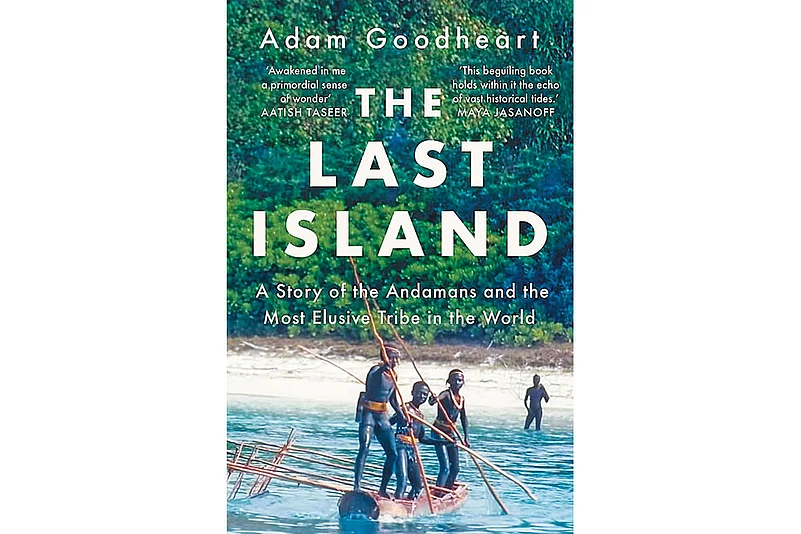

About a year after the evangelist’s tragic killing at the hands of the Sentinelese, the author (now a historian), Adam Goodheart, returned to the Andamans. His latest book, The Last Island: A Story of the Andamans and the Most Elusive Tribe in the World, draws from these expeditions, besides published texts and other primary sources.

Part travelogue and part narrative history, The Last Island is touted as “the first full-length book” on North Sentinel. However, it hardly offers substantial insights on the island beyond existing knowledge. The book unfolds across four chapters, covering around 180 pages of text and over a dozen black-and-white photographs and maps. Nearly half of it diverges from the Sentinelese, while a large portion merely reiterates Goodheart’s 2000 article, with added corrections and information.

The Last Island endeavours to navigate the extensive history of the Andaman islanders, connecting their colonial past to contemporary times. However, it lacks rigour. The narrative often falters due to inadequate details and perspectives, causing confusion and distorted comprehension, especially for readers unfamiliar with the complex history of the Andamans.

The absence of proper citations makes the verification of the author’s claims difficult, diminishing the book’s credibility and impeding readers’ ability to engage with its contents critically.

The Last Island exposes Goodheart’s disregard for research ethics, raising serious concerns about researchers’ responsibility while conducting studies in sensitive and protected environments. The author’s deliberate criminal trespass into the Sentinelese tribal reserve by enticing a hesitant and economically disadvantaged local fisherman with significant monetary incentives is particularly disquieting, among others.

The Andaman Islanders thrived in complete isolation until the British colonised them. Goodheart delves into their history but barely learns anything from it.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, scores of thrill-seeking Europeans thronged the “Human Zoos” where “savages” (indigenes) of the world were exhibited. Goodheart’s “wild adventure” to the North Sentinel was fuelled by similar sentiments—the exhilaration of a human safari—that he wanted to narrate to his friends for decades. “Chau’s and my dreams were perhaps more similar than I would like to admit... Unlike him ... my quest was not to shift the course of history, just to witness it,” he writes.

Goodheart was aware that trespassing into a protected reserve endangered a highly vulnerable Sentinelese people without providing him any opportunity to deepen his understanding of their society. Over two decades later, he perversely justifies his illegal action thus: “To seek such a moment of sublime experience … may be a foundational human desire. A pardonable sin.”

Goodheart also gives a detailed account of his first contact (a criminal offence) with the Jarawa in the late 1990s and of another human safari during his second visit to the Andamans. “I violated the rules and lowered a window ... Right alongside the road ... was a man. Naked, perfect, as taut and upright as the bow ... It felt suddenly intimate to have our faces so close ... The hunter looked right through me, his eyes as cold as any I have ever seen,” Goodheart narrates his encounter with the Jarawa.

For centuries, indigenous communities have endured the theft of their ancestral remains and cultural artifacts. The UNESCO 1970 Convention attempts to curb the illicit trafficking of cultural property globally. Similarly, in the United States, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, 1990, facilitates the return of stolen cultural objects to their rightful owners.

The Last Island recounts how the colonists robbed the sacred and cultural possessions of the Andaman islanders. However, it also reveals another disconcerting fact. During a conversation, a scrap dealer in Port Blair proudly shows his most coveted possession—a Sentinelese bow—to Goodheart. Enthralled by its craftsmanship, Goodheart instantly attempts to purchase it. Such an unethical and illegal act—trafficking of cultural property of the Sentinelese—undermines their survival and spiritual well-being, perpetuating the historical injustices inflicted upon the Andaman islanders by the colonists.

A litmus test for any work on North Sentinel is how it impacts the Sentinelese or the discourse on such societies. Globally, approximately 200 indigenous communities, comprising around 10,000 people, live in voluntary isolation, with a majority of them concentrated in the western hemisphere. The social, economic, spiritual, and cultural well-being of these communities depends on their relationship with their ancestral lands and natural resources.

India’s “eyes-on, hands-off” policy respects the Sentinelese’s right to self-determination and no contact, thus guaranteeing them the right to land and to live freely according to their culture and without any discrimination. It aligns well with the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) guidelines for the protection of indigenous peoples in voluntary isolation and initial contact.

Contrastingly, The Last Island strips the Sentinelese of their agency, and confuses its readers. “Chau’s secular critics—all the well-meaning bloggers, tweeters, and activists who want the outside world to leave North Sentinel Island in eternal isolation —are just as delusional, just as much in thrall to their own mythology,” argues Goodheart.

Having migrated out of Africa some 70,000 years ago, the Andaman islanders thrived in complete isolation on these islands until the British colonised and ravaged them in the 19th century. The Sentinelese continue to hold their last bastion.Goodheart delves into the history of the Andaman islanders but barely learns anything from it.

(Views expressed are personal)

(This appeared in the print as 'Silencing The Sentinelese')

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

Ajay Saini is Assistant Professor at IIT Delhi. He works with remote indigenous Communities