On September 23, 1996, Silk Smitha was tragically found deceased in her Chennai apartment, abruptly ending a promising life caught between fame and solitude.

She challenged South Indian orthodoxy, embracing glamour while demanding dignity on and off the screen.

Twenty-nine years later, her legacy endures as both transgressive and tragic.

On September 23, 1996, at thirty-five, Smitha’s tragic death in her Chennai apartment shook the film industry. The immediate verdict contemplated suicide, but the public conversation that followed revealed as much about those speaking as it did about the woman who had just passed away. Gossip and speculation about addiction, ill-treatment by producers, co-actors, and private heartbreak crowded the discourse, while the structural violence that shaped her life received only sporadic attention. A translation of the letter discovered in her Chennai apartment read: “Only I know how hard I worked to become an actress. No one loved me.” This is the festering wound beyond the glamorous legacy of a woman, whose name was synonymous with transgression. On her 29th death anniversary, the question still irks—for a woman who made a career by commanding attention, why was she treated with so much indifference and contempt? Why wasn’t she grieved and honoured, even in death? Hers is a story that has become a cautionary tale of an industry that devoured its own.

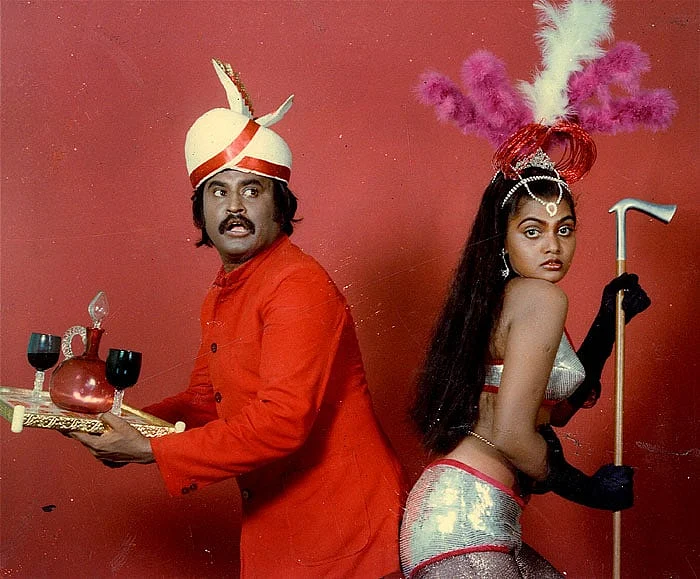

The 1980s cinema machine gave women only two fates: saintly mother-wife or vampish seductress. The good woman existed to preserve lineage and reputation. The bad woman existed as spectacle, an “available object”, or a narrative foil whose presence justified male desire and moral condemnation. Smitha, born Vijayalakshmi, fell into the latter—her “disobedient” body made to embody sexuality that upper-caste heroines were not allowed to show. Was it rebellion, or was it coercion disguised as choice? Perhaps both. Her power, however, was undeniable. She knew she was being objectified and decided to weaponise it. The vamp that patriarchy created became a powerhouse that held patriarchy hostage. She owned her sexuality, turned shame into spectacle, and reminded audiences that a woman at ease with her body could be terrifying to men who claimed to control it.

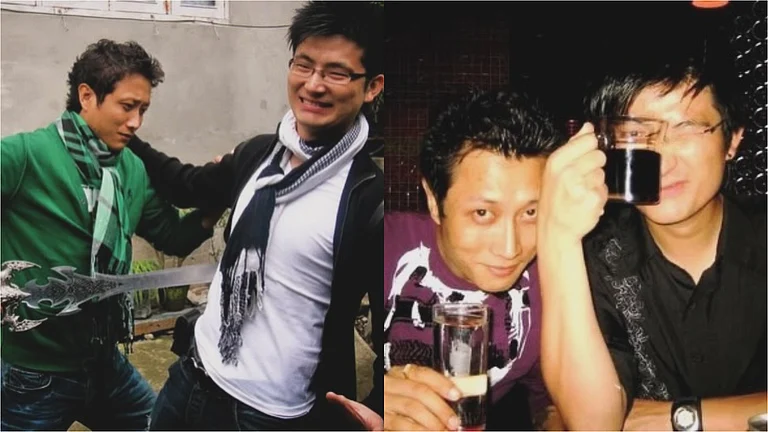

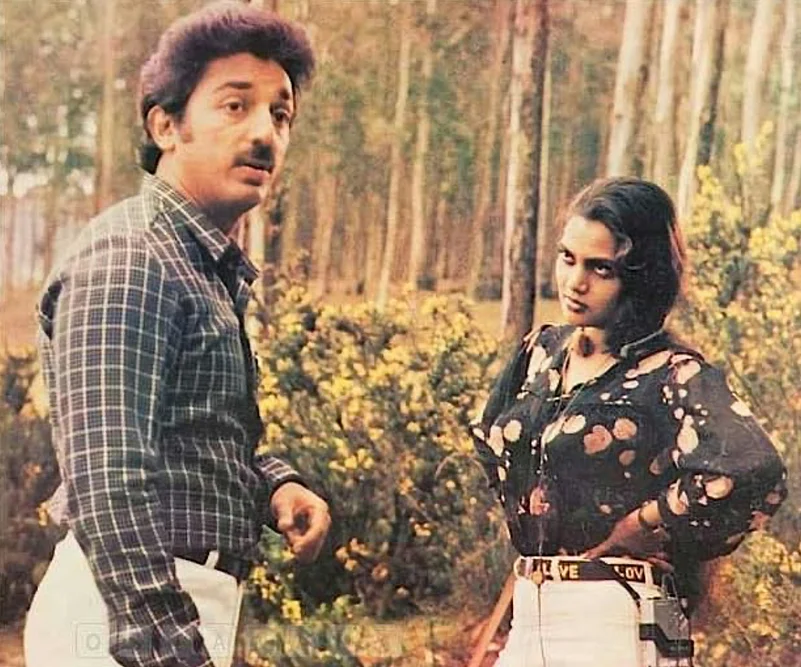

Public memory flattened Silk Smitha into a few durable images: the vamp, the seductress, the commodity. That image was manufactured by a film economy in which the producer and the director not only owned the means of production but also the register of value. Despite appearances in Malayalam, Telugu, Kannada, Tamil, and Hindi films and working with marquee names like Kamal Haasan and Sridevi, she seldom received the social prestige or the critical seriousness afforded to other performers. Actors like Smitha were assigned roles that reflected social hierarchies; their worth measured by box office promise rather than social or artistic respect. The irony is bitter: the industry mocked her, yet relied on her presence to guarantee box office success. She worked in over 450 films, commanded fees no heroine could dream of, and even designed her own costumes. Yet, none of this amounted to her being understood as a multi-dimensional actor.

Smitha wanted to be defined by character work, which the industry repeatedly refused. Acting gave her financial independence and public visibility, yet the roles available to her were tightly policed by producers’ tastes and audiences’ expectations. Smitha cultivated a persona that allowed her to profit from that visibility. There is an audacity to that survival strategy. When a woman who chooses to be visible acts with intelligence and agency inside a coercive structure, how should she be judged? Many of the cultural responses to Smitha answer that question with contempt.

Caste plays a central, often ignored role in how these binaries were policed. The vamp or the vampish body has historically been coded as lower-caste and therefore licit for sexualisation. Upper-caste female bodies were meant to preserve honour through invisibility and decorum. Women from marginalised backgrounds were made repositories for the industry’s fantasies about immorality. The consequence is predictable: sexual violence and casual exploitation are explained away or normalised because the target is culturally imagined as available. Smitha’s body was read through these lenses. Her screen presence doubled as a critique, deliberate or otherwise. Beyond the camera, she fought for dignity in the workplace—famously halting a shoot when crew members lacked safe drinking water. To friends and colleagues, including co-actor Anuradha, she endures in memory not only as a star, but as a woman of biting wit and disarming humour. In turn, the very industry that commodified her tried to humiliate her privately and diminish her politically.

Smitha left an abusive early marriage at the age of fourteen. Poverty interrupted her schooling and sent her into labour and survival strategies that would eventually lead her to cinema. The transformation from touch-up artist and uncredited extra to ubiquitous screen presence is a rags-to-riches trope in headlines; yet, it flattens the quotidian violence she had to endure. Vinu Chakravarthy saw her potential for screen, and in Vandichakkaram (1979), she played a bar girl named Silk—a name that would eclipse her own. Stardom brought financial independence, but also the shackles of typecasting. She was asked to tone down her “heat” for family dramas, only to be summoned again when producers needed a song that would set theatres buzzing. Directors and superstars asked for her in films—Rajinikanth, Chiranjeevi, and Sivaji Ganesan were among those who wanted at least one song featuring her.

So why did mass success not translate into dignity? Part of the answer lies in the genre work that became her hallmark. Many of her films were judged by critics and gatekeepers as B-grade or soft-core by Indian standards. Such genres enjoy mass appeal and commercial reward, but they rarely offer critical respect. The same films that made her famous were invoked to justify her dismissal as a serious artist. Contrarily, the very qualities that guaranteed audience fascination—garish makeup, short costumes, and bold choreography—became shorthand for immorality in conservative commentaries.

Personal heartbreak and dependence on substances are part of the narrative that circulated after her death. She is linked in many versions to a long relationship with a doctor identified in reports as Dr. Radhakrishnan, and later with other men whose loyalties were questioned in posthumous inquiries. Her letter, dissected and translated roughly into public readings, speaks of betrayal and exhaustion. If the letter is to be read at face value, it documents a woman who felt used and isolated, who believed her life’s labours had been repaid with theft of trust and possessions. At the same time, conspiracy theories propose murder, alleging that powerful men had reasons to silence her. Both narratives—the intimate and the conspiratorial—testify to a wider problem: female bodies and female stories are often interpreted through sensational frames that prefer scandal to systemic critique.

The pattern of tragic ends among visible women in the South Indian industry during the late twentieth century is chilling. Names recur: Disco Shanthi, Jayamalathi and Sasikala, among others. Many of these women shared trajectories of exploitation, precarious work, and narratives of broken relationships. The social and industrial culture of the film world in that era produced conditions that made certain deaths possible and certain explanations convenient.

In the years after her death, Smitha’s legacy has been reappraised. Filmmakers in Hindi, Kannada and Malayalam have attempted to narrativise her life, to retrieve complexity and the human cost. Fan pages on Instagram and Facebook keep circulating rare photographs, trivia and clips from films like Moondru Mugam (1982), Kanchana Maami (1982), Kottai Vasal (1983), and Silk Sakkath Hottey (1988). Popular culture’s appetite for revival and reinterpretation reveals two simultaneous impulses: one, to indulge nostalgia for a star whose image defined an era; two, to correct the historical record by insisting on a fuller account of personhood.

What remains most striking about Smitha’s story and the films that were made in her memory is the way her life exposes the film industry’s moral vocabulary. She lived in the space between exploitation and mastery, between humiliation and high pay, between yearning for romantic fidelity and the transactional realities that shaped relationships around fame. Her life’s tragedy lies in the fact that the industry rewarded her public body while denying her private dignity. She remained unapologetic about her body, even as she was being shunned because of it. That insistence on being physically present, glamorous and ambitious is itself a rebuttal to the industry and to social expectations. This visibility had costs, and those costs were gendered and caste-inflected. Smitha’s life compels us to see that cycle, to ask structural questions about who profits and who pays the price.

Finally, her life invites a crucial ethical demand: to treat performers, especially those on the margins, as whole persons. To ask about the circumstances that produced suffering is not to exonerate self-destructive acts. It is to insist that systems of entertainment and social prestige be accountable. Smitha remains a figure who resists neat categorisation. She was glamorous and ordinary, powerful and vulnerable, strategic and deeply wounded. Her screen presence was defiant in its willingness to claim desire, and her off-screen life was tragic in how it revealed the limits of human care inside an exploitative culture. Remembering her should mean both acknowledging her charisma and confronting the industry that commodified and then abandoned her. Only then can her legacy be anything more than the sum of scandal and spectacle.