Summary of this article

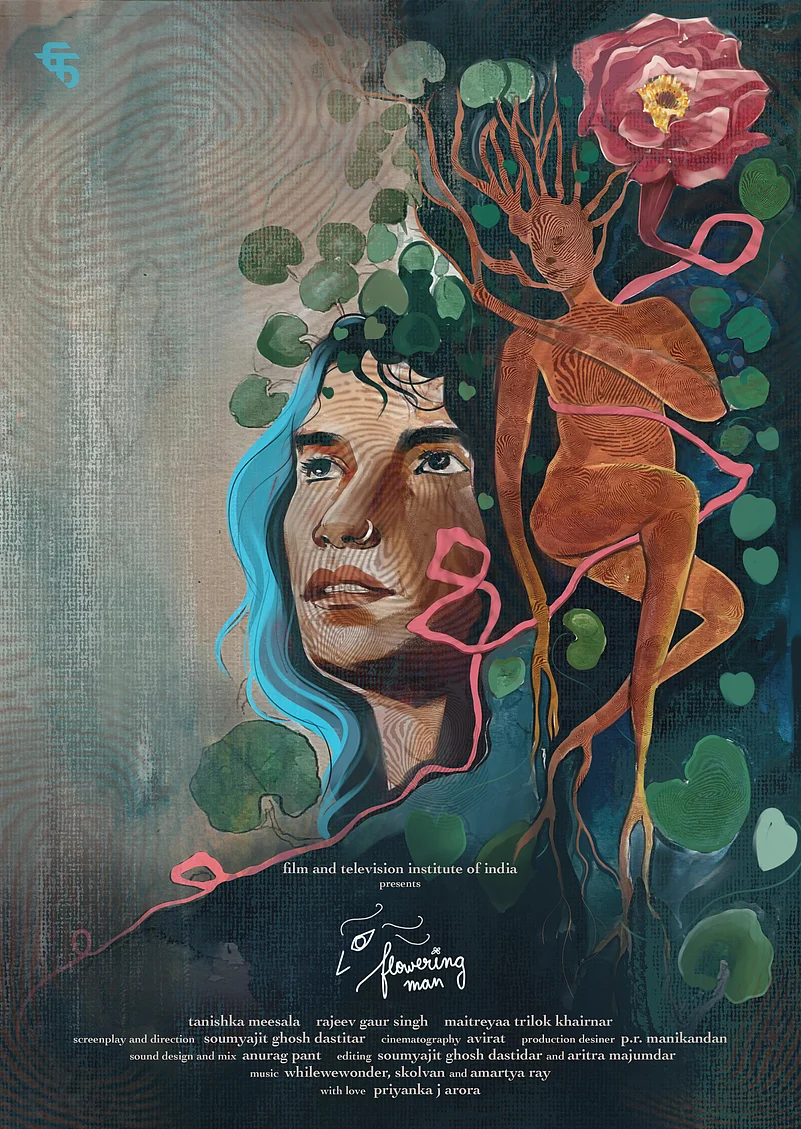

Flowering Man (2023) is directed by Soumyajit Ghosh Dastidar.

It won the national award for Best Non-Feature Film in 2025.

Flowering Man is not a conventional coming-out story; it is about the labour of acceptance, about what it takes to accept not just oneself but another.

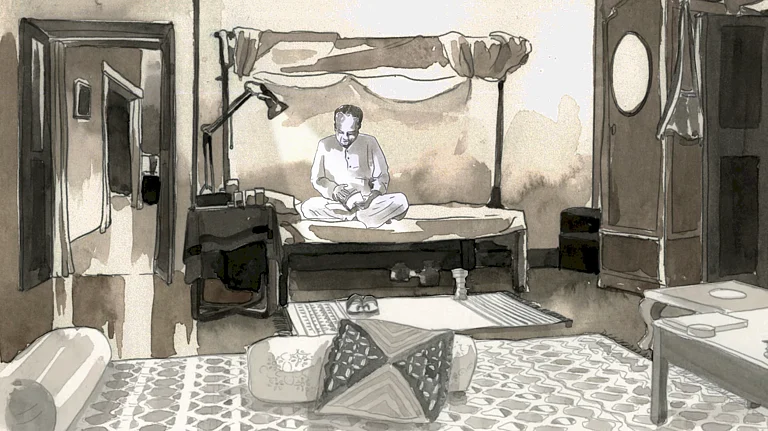

A flower blooms from a man’s mouth, while their daughter seeks a scent both familiar and impossible to name. Directed by Soumyajit Ghosh Dastidar, Flowering Man (2023) won the national award for Best Non-Feature Film in 2025. The film follows Sashi (Rajeev Gaursingh) and their daughter’s (Tanishka Meesala) relationship under strange circumstances. Sashi transforms into a plant that grows from their mouth and their daughter must accept this transformation and let go of a parent as they once were. But this situation is not unreal or impossible, because dreams allow anything. The film creates a surreal, dream-like world to explore identity and the courage required to accept oneself and others.

The film begins with the daughter narrating about Sashi, her father. Her narration is unreliable, fragmented and guided by her own feelings and memories. She tells us about a smell, familiar in its strangeness; but as the audience, we can only imagine. This gap between her experience and ours is not incidental. Ghosh Dastidar has placed it there deliberately and it is in this gap that the film locates its meaning, in the space before words arrive, where we can only look and recognise.

Within the narrative, the unknown smell guides everything. We begin with a search for the smell, for the father. The daughter looks through the hanging sheets as the camera lingers on her face. A train passes as if to mark the changing stages of life. The train will pass again before the film ends, to mark yet another stage—her loss of the father she knew and the consequent acceptance.

The father’s gender transformation does not announce itself. There is no confession. There is no confrontation. A plant grows from their mouth instead. Speech becomes impossible. And the daughter watches. She does not ask why. She does not demand an explanation. She learns to live with what cannot be explained.

This is not just an aesthetic preference. This is what happens when there are no words. Eight years after Section 377’s decriminalisation, India exists in a strange suspension. Queer existence is legal. Same-sex marriage is not. The culture has not yet caught up to queer existence. Western queer cinema has spent decades building its conventions of coming-out stories, identity politics and visibility as liberation. But Flowering Man arrives with a different grammar to tell this story, not only because the filmmaker prefers metaphor to directness, but because metaphor is the only language that exists when the culture offers none at all.

Flowering Man is not a conventional coming-out story, though it is certainly about coming out. It could have easily been about Sashi’s pain and the difficulty of gender transformation. But it is not. Instead, it is about the labour of acceptance, about what it takes to accept not just oneself but another. No one is speaking their truth here out loud; rather, one is accepted without any need for words. The narrative gives its time to the daughter. It explores the journey of those who must go through their loved ones’ transformation. It is about how they learn to accept, even if they struggle to understand; how they try to find the familiarity of old ways in the new form of existence. This inversion is significant. It reveals the reality of queer existence and lived experience in India—how Indian families absorb queer identity not as an individual truth but as a collective wound. The suppressed parents’ turmoil eventually reaches the child. And the film explores this intergenerational queer trauma that one endures in a society still ashamed of queer existence.

There’s one scene I keep going back to, again and again. Sashi rides behind their daughter on a scooter, the flowering plant sprouting from the mouth as they move through the streets. There is something both ordinary and surreal about this image—a daughter riding with her father, except her father has become something other than what fathers are supposed to be. This simple contradiction holds the film as a whole, and not just as an element between the scenes before and after.

It could have been played for revelation quite easily. But here, the filmmaker chose to domesticate the surreal. The impossible becomes what you live with daily. And this becomes the syntax of suggestion in Flowering Man. It delves into the grammar of symbolic displacement that one needs to tell this story in India, where queerphobia is still predominant, where it claims victims every day.

Flowering Man plays with imagination and the limits of the medium from time to time. The way we see things is affected by what we know or what we believe. It fragments the frames and creates dream-like, imaginable pieces that hold onto trauma. This translates to the daughter when she hears her father’s screams in her hostel. She flinches in pain until she learns to imagine clouds and talk to them and blow them away like her father did. Talking to the clouds requires a language that is there—but to see it is a choice. Afterall, we only see what we look at. The daughter refuses to; she remains strangled by the nostalgia of her father and resists who Sashi is becoming. The cassettes and the old songs prevent her from moving to this side of language, where she can speak to her father. Her trauma, passed down from her father, suspends her.

The film follows her transit to a space where she finally accepts her father,and it is love that guides her. The sight of love has a completeness which no words or embrace can match; it can only be realised by the smell. In the end, it is the scent that shows her the likeness, how she still carries Sashi within her and this recognition creates a haven that lets her finally rest.

Tanishka Meesala plays the daughter. She does not perform so much as withhold and allows the film to unfold. Rajeev Gaursingh, as Sashi, works in gesture and expression; he communicates what language cannot. Avirat Patil’s camera maintains a certain distance. It does not exploit. It could have—the conceit allows for it—but it does not. The editors, director Ghosh Dastidar himself along with Aritra Majumdar, let the film run on its own clock. Surreal dream-like situations require time. They require breath. Nothing here is rushed. The transformation—both literal and metaphorical—unfolds as it must, slowly.

But a question persists: whether the language that Flowering Man employs to address a queer story in India’s current socio-political climate is temporary; whether it will dissolve with legal recognition or endure.

Films across decades and geographies have discovered new languages to meet the pressures of their political moment. Flowering Man is not an exception. It is very much a product of the present time’s limitations. But it is also an artistic choice. The film has already discovered its own grammar. Its refusal to tell the conventional coming-out narrative is not only because it cannot access such a story creatively, but because it has found something more precise and honest to the present Indian context. Ghosh Dastidar made an artistic choice here to follow a form that reflects the country’s socio-political weather. In the space between legality and recognition, between visibility and language, he created a film that belongs entirely to this moment. And we can only hope that such a language sustains itself. The current scenario certainly requires it.

In the final scene of the film, we do not see Sashi at all. There is only the flower, the one in their hair and it looks back at the camera and joins the spectators in the act of seeing. The film achieves a different way of seeing, where the flower is placed on display, and the flowering reveals itself. What they see reminds them of their identity. The daughter finds her father not in memory but in metamorphosis, following the scent of the flower they are becoming and choosing to look at them with love.