One has to marvel at the disillusionment of the producer and director who once made a feeble case to claim that the film Dostana (2008) normalised homosexuality in Indian households. I was in eighth grade when the film was released. I remember how, after watching the song “Ma Da Ladla Bigad Gaya,” one of my classmates trilled merrily about the "abnormal" nature of the relationship between John Abraham and Abhishek Bachchan—as if that were the central theme of the story—and we chuckled dismissively. If that was mainstream Hindi cinema’s first introduction to queer relationships, then might I add: it was a lousy and irresponsible one.

It would be gutting to learn that, years later, this film—featuring Kirron Kher beating her chest and scurrying about, trying everything she can to "heal" her son’s supposed medical condition (read: homosexuality)—is being upheld as the one that normalised queerness. A film where the gay characters aren’t even gay, just pretending to be, all the while vying for a woman’s attention. Perhaps it really is that easy to set narratives these days—even with a film that treats homosexuality as “bin bulaiyan yeh bimariyan.” But let me sidestep the lure of a tirade and instead focus on three early Hindi films that deserve credit for representing queer relationships without reducing their characters to mindless capering or making duds of them for a few low-hanging cackles. With a sensitivity that has been rare in Hindi cinema, varied dimensions of queer existence emerged through what was said, what was implied, and what was allowed to linger in silence within these films.

Badnam Basti

Regarded by many as the first queer film of India, Badnam Basti (1971; dir. Prem Kapoor) would have been lost forever if it weren’t for Simran Bhalla, a postdoctoral fellow at Northwestern University, who—in 2019—procured a copy that had been sent to a film festival in Germany decades ago. Adapted from Kamleshwar Prasad Saxena’s novel Ek Sadak Sattavan Galiyan (1979), this film portrays a love triangle among two men and a woman—and hard as it may be to imagine today, it was funded by a government-run film corporation.

Interestingly, the film captures moments of intimacy not through grand confessions or sweeping gestures, but through acts of service as a love language. When Sarnam Singh, the protagonist, notices Shivraj—a temple worker—stranded by the roadside, he offers him a ride on his truck. Later, when Shivraj is turned away from his own home by his stepbrothers after his father’s death, Sarnam takes him in. There’s a moment where Sarnam says, “Tumhe toh jalebi achhi lagti hai na?” as he holds out a small parcel of sweets wrapped in leaves, along with a bunch of fresh flowers. Shivraj, in turn, picks up shards of glass from the floor when Sarnam drops them in a drunken stupor, or lifts him off the ground each time he passes out. Love, between them, is built on the steady foundation of showing up. Their interactions often play out to the sound of cheerful classical instruments, a familiar cinematic cue that has long been used to steer audiences’ emotions in directions considered palatable for the times. What emerges between the two men seems strikingly organic: two people, long uncared for, learning to care for each other while living together.

Fire

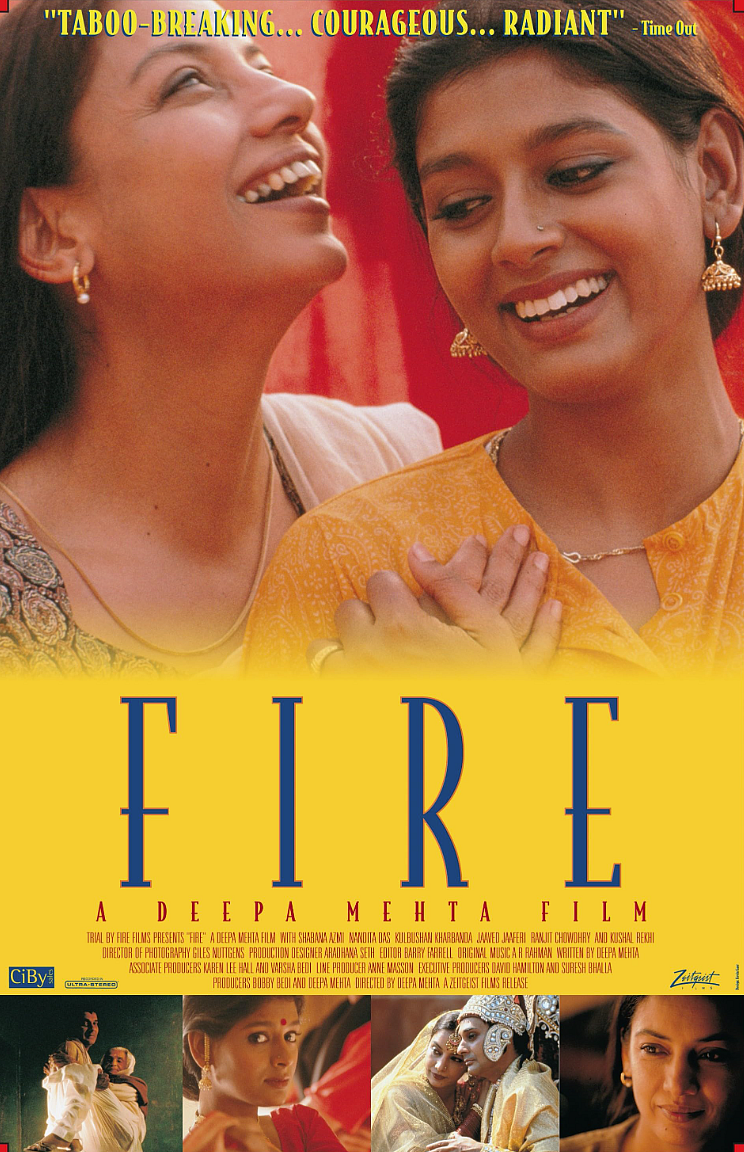

If one were to take a close look at Deepa Mehta’s Fire (1996), one would find multiple love languages shared between the protagonists. With the release of Fire in 1996, all hell broke loose. Shiv Sena vandalized movie theatres, and the word “lesbian” erupted into a full-blown national scandal. The film cast a searing light on oppression, longing, and the dimly lit corners of a crumbling Delhi household. Radha and Sita—names the Shiv Sena later cited in their outrage as insults to Hinduism—are two women married into the same suffocating joint family, who find in each other what their husbands withhold: attention, desire, and above all, the freedom to want.

The men are predictable: one piously obsessed with religion, the other with his mistress and pornography. Both are narcissists—committed to a kind of emotional absenteeism that drives the women to the brink, and eventually, to each other. Intimacy and tenderness unfold in glances exchanged across kitchen thresholds, in fingers grazing shoulders, in conversations thick with the unsaid. In the absence of meaningful male companionship, the women begin to spend long stretches of time together—at markets, shrines, on the rooftop soaking and drying clothes. This shared rhythm of everyday chores becomes a love language in itself. Gifting, too, becomes a tender form of expression: Radha gives Sita bangles to wear, when she oils Sita’s hair in a gesture of intimacy. Mehta, while drawing on several familiar tropes of love languages, deliberately uses physical space and color in lockstep with the story she tells. Among other warm tones, the color red—appearing in clothing, bindi, lipstick—emerges as a symbol of defiance and reclamation, in stark contrast to the cold and neutral undertones of Mehta’s frames.

My Brother…Nikhil

When speaking of love languages in the portrayal of queer relationships, one cannot overlook My Brother… Nikhil (2005, dir. Onir), where caregiving emerges with its own emotional vocabulary—stretching across acts of service, physical touch, and quality time. Set in 1980s Goa, the film follows Nikhil Kapoor (Sanjay Suri), a national swimming champion, a son, a brother, a lover, whose life is upended after he is diagnosed HIV-positive. The state detains him, the sports federation abandons him, his parents retreat into silence and shame. Overnight, talent isn’t enough. Kindness isn’t enough. Being a good son, a promising athlete—none of it is enough to shield him from what the world has already decided he deserves: isolation and retribution.

Besides his sister Anamika (Juhi Chawla), it is his partner Nigel (Purab Kohli) who becomes his quiet anchor—not guiding him toward some redemptive arc, but toward dignity. Queerness here is wrapped in grief, diagnosis, and acts of consolation. From handing out pamphlets demanding Nikhil’s release, to sitting beside him post-transfusion, to wordless evenings by the sea—Nikhil and Nigel insist on tenderness even in the face of shoulder-dropping grief and systemic erasure. Their love glimmers through their resilience and grace.

The cinematic archive of queer India is often embattled and burdened by decades of silence—but it is never forgotten. Regional films—deserving their own dedicated essay—have been telling queer stories in distinct voices for decades, tugging at the seams of India’s carefully stitched silence. From Badnam Basti’s defiance to Fire’s blazing rupture and My Brother… Nikhil’s tenderness, these films lay bare the battle scars that paved the way for works like Aligarh (2015), Margarita with a Straw (2014), and even Sheer Qorma (2021). Each pushed the boundary an inch further. Queerness here is no polished narrative shot in the sanitised locales of Miami Beach, set to songs like “Shut Up and Bounce” (yes, Dostana, still glaring at you) for easy consumption. It is jagged, urgent, and too fierce to be airbrushed.

Sritama Bhattacharyya has an M.Phil in Women’s Studies from Jadavpur University, Kolkata. She is currently an English Teacher based in Washington