Jamli Mohalla, located around Bapu Khote Street in south-central Mumbai, is densely packed with traders of all kinds—glass works, iron and steel merchants, acrylic stores, furniture makers and more. In the middle of this typical, old-world street is the small shop of Mohammed Ismail, a custom furniture maker. He was previously a dhaarwala, a knife sharpener, having inherited the business set up by his grandfather who moved to the city from Iraq in the 1930s. Ismail Bhai was also a former member of the appropriately named ustra (folding razor) gang, headed by his nephew Hussein, who he says was a sharpshooter often contracted by the police for hit jobs on other gangsters. Hussein paid the ultimate price for his association. Betrayed by his own aunt, he was shot dead in 1987. But not before making his mark. As Ismail Bhai says: “Hussein ne bahut wicket gira diyela hai” (“Hussein took many wickets”).

The entire phrase—with its cricketing metaphor, Marathi influence, and the cadences with which it is said—deftly demonstrates the collective heart and soul of Mumbai/Bombay, inhabited as it is by diverse ethnic, linguistic, religious, social and economic groups, all jostling for literal and figurative space while trying to grasp the grand, often illusory, mythic allure of the city. Ismail Bhai speaks Bambaiya. In particular, his speech is heavily laced with bhai-giri, the street style of taporis—wannabe thugs, wastrels, roadside Romeos, smart alecks, and of course, the quintessential fast-talking and endearing Bombay hustler of Hindi cinema. While Bhai is bro, the suffix giri is a mode of operation, code, style or trend. The successful Bollywood franchise of Munnabhai popularised Gandhigiri, a snappy expression to describe rightful civil disobedience, in its filmic scenarios of the good fight. The crowd-pleasing film dialogues found great favour, propagating the quirky, entrepreneurial, inclusive and fun side of the city that belonged to all. From stockbrokers to gangsters, rickshaw drivers to civic workers, gym instructors to film stars, one common idiosyncratic and beguiling tongue is heard on the streets of akkha Mumbai. Is this then the true essence of the city, wafting about effortlessly bringing together all its inhabitants? Is this the glue that binds the disparate metropolis?

The writer, journalist and raconteur Rafique Baghdadi, who grew up in the central district of Mazgaon, says Bambaiya was made popular by Hindi cinema. It existed all around him, with the influences of predominantly Konkani Muslims and Goan and East-Indian Catholics of the area. Hindi cinema has always mined the street for characters and their colourful ways. Baghdadi has been conducting a Sa’adat Hasan Manto walking tour for many years, traversing places the iconic writer lived, worked at and frequented. Manto often wrote empathetically of street life in Bombay, but his characters rarely speak the language of the street. In one story, Dhondu, the pimp at the street corner outside Manto’s favourite restaurant Sarvi, opposite Nagpada police station, complains about the melancholic, moody prostitute Siraj, saying, “Saali ka mastak phirela hai” (“The bitch’s head is screwed up”), indicating his Bombay street cred. Manto rarely used Bombay slang, choosing instead a standardised literary Hindustani/Urdu, which in many ways is the dominant spoken language of Hindi cinema. However, in the Hindi novelist and TV scriptwriter Manohar Shyam Joshi’s vertiginous, enigmatic post-modern novel Kuru-Kuru Svaha, a set of corresponding characters to Manto’s story, Manohar the narrator and Babu the pimp, have an entire Bambaiya exchange on Chowpatty beach. Babu’s succinct proposition “Tafri hone ka?” (Want some fun?) elicits a phoney enquiry from Manohar, and in reply Babu mentions a “nava gharelu chhokri”, a new, homely girl, who he says: “Abbi kiska saath baitha nai. Usku rupya ka jarurat. Din ka time hi aayinga. Pachas rupya lenga. Bolo hone ka? (She has not ‘sat’ with anyone yet. She is in need of cash. Will come only during the day. Takes Rs 50. Tell me, you want?) This typical Bambaiya with its unique inflections and word choices, is richly suffused with the cool breeze of the Arabian Sea, the ubiquitous odour of drying fish, the comforting clatter of local trains, the promiscuous density of slum dwellings and chawls, and the salty perspiration of the industrious, enterprising city.

The multi-talented actor, dancer and comedian Jaaved Jaaferi has often played Bombay street characters. Talking to this writer recently, he says he picked up cues from his father Jagdeep’s screen roles, which were drawn from the legendary Hindi film comic’s experiences of living on Bombay streets in the 1940s. Jaaferi grew up in the Catholic suburb of Bandra, but picked up influences from local trains, attending Muharram in Bhendi Bazaar every year, and the film community at large. This would all innovatively reflect in his collaboration with the writer Arshad Syed, director Shahid Sayed and researcher Imtiaz Baghdadi in Jafferi’s iconic sketches for the mid-1990s Channel [V] TV show Timex Timepass. Notably, during the late-1990s, his rap song Mumbhai for the film Bombay Boys, dexterously showcased Bambaiya, in all its filmy glory. Jafferi however, points to Guru Dutt’s classic noir film Aar Paar, which featured a young Jagdeep, as an outstanding example wherein several characters speak typical street slang.

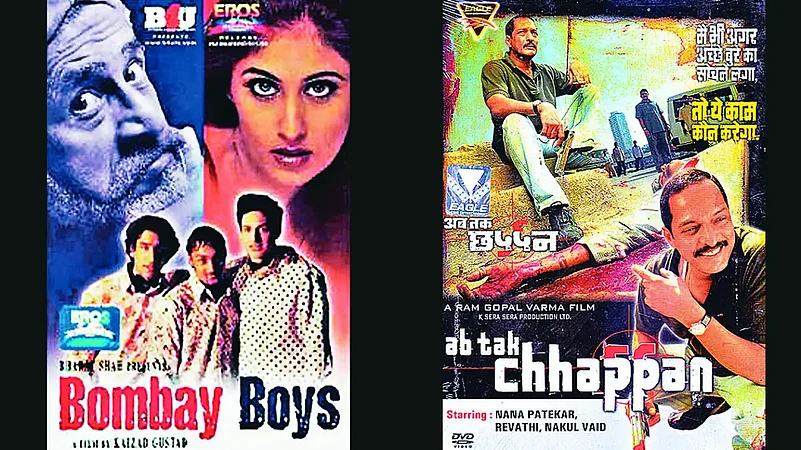

Bambaiya has mostly been used for comic effect on screen, but as Arshad Syed says, the gangster films of the 1980s and 1990s—including Naam, Gang, Satya, Vaastav, Company, Ab Tak Chhappan, among others—had characters speaking Bambaiya with varying degrees of authenticity. The cheeky and charming song Aati Kya Khandala from the film Ghulam, transformed into a popular catchphrase, illustrating as it were, the symbiotic, recursive relationship between the screen and the street. And actors such as Jackie Shroff, Arshad Warsi and Govinda truly embody the Bambaiya spirit, even if their screen characters are often more standardised. The 1988 outlier Salaam Bombay, is also notable for its authentic street depictions and dialogue. It is rare though, that the main lead in a Hindi film speaks entirely in Bambaiya. Three exceptions shine through: Amitabh Bachchan in Amar Akbar Anthony, Pawan Malhotra in Salim Langde Pe Mat Ro and Sanjay Dutt in the Munnabhai franchise. As Jaaferi, Syed and Baghdadi say, writers, actors and directors draw from their immediate surroundings to give authentic colour to Bombay characters. The most adept at this, all point out, were director Manmohan Desai, screenwriter Abrar Alvi, and writer/actor, Kader Khan, who Baghdadi says, never really got his due.

Salim Langde Pe Mat Ro, directed by Syed Mirza, is set in Dongri, the heartland of Bambaiya. As a review by Nandini Ramnath points out, in Mirza’s words, the lead character of this iconic film exploring the “social reality of a young, Muslim and uneducated hoodlum along with history”, declares in typical street style: “Apna bhi time aayenga re.” (“Our time will also come man”). The Bombay underdog knows that it’s all within his grasp. This aspirational expression has found its way into the recent hit film Gully Boy, wherein Bambaiya is infused with the contemporary flavours of rap and hip-hop. Salim Langde Pe Mat Ro, however, remains outstanding in how Bambaiya remains very close to the street. Reflecting the world of gangsters, grifters, and hustlers, Salim is nicknamed langda or lame. There are many other Salims, his character informs us at the very outset—Salim Chechak, Salim Kania, Salim Tempo, Salim Honda. Identified by their physical attributes (pockmarked, cross-eyed) or by the vehicle they use (Tempo, Honda), these nicknames are a common feature in the Bambaiya realm. Gang members or even local thugs, are often chaptya (flat-faced), taklya (bald) or machmach (blabbermouth), as the late associate of Chhota Shakeel (chhota indicating small or younger), Fahim Ahmed Sharif from Bhendi Bazaar, was known. This heartland of Bambaiya, of Mirza’s film, of Ismail Bhai’s neighbourhood—Kamathipura, Nagpada, Dongri, Muhammad Ali Road, Pydhonie, Zaveri Bazaar, etc.—is the realm of mawaalis—a polysemous Arabic word (the plural of mawla from the root waly) originally used for non-Arab Muslims in the subcontinent, which, over time, fell into semantic pejoration (the gradual depreciation of a word’s value) to refer to undesirables, goons and criminals.

The work of Abdus Sattar Dalvi, the founding head of Mumbai University’s Urdu department, has explored the linguistic history of Urdu in Bombay and Konkani Muslims. The first extant example of Bambaiya he says, is the autobiography of a migrant from Kathiawad named Haji Bhai Miyan, the patriarch of the renowned Tyabji family. He chose to record his memoir not in his mother tongue Gujarati, but in a hotchpotch of the spoken forms of his adopted home. Featuring the ubiquitous kanda-batata, a phrase combining a Marathi word with a Portuguese one for the household staples of onions and potatoes; as well as Gujarati/Marathi lafda and vanda (quarrel/problem and issue), this early exemplar served to perhaps codify an evolving city dialect. Earlier still, the narrative historical Marathi text Mahimchi Bakhar or Mahikavatichi Bakhar dated to the mid-15th century, integrated some proto-Urdu words for descriptions of military campaigns. The word bakhar itself is a metathesis of the Arabic khabar (news or information). Over the centuries, diverse influences appeared in travel accounts, poetry, and other writings, broadening the word pool and the realm of Bambaiya.

With the various spoken forms of the native Kolis, Pathare Prabhus, Kunbis and Bhandaris of the region; Gujarati traders, proselytising Sufi saints, Parsi merchants, Konkani fisherfolk, Marathi educated elite as well as provincial millworkers; the migrant labourers from UP, Bihar, Telangana, Andhra and Tamil Nadu; the entrepreneurial hoteliers from Mangalore and small vendors from Malabar; and the linguistic registers of various tradesfolk such as kite makers, weavers, washer folk, etc; as well as, the profound colonial influences of Portuguese and English, and the administrative influences of Persian; the complex tapestry that forms Bambaiya is an the inclusive umbrella that brings all under its ragtag oneness, as residents codeswitch nimbly, participating in each other’s linguistic quirks by sharing interoperable words, phrases, sounds and accents. This linguistic unity remains mostly intact despite the political actions of privileging Marathi as the true language of the region. Beyond all this is perhaps what most people say Bambaiya is: the tangy, tart, spicy, sweet, crispy, soggy, crunchy anarchic flavourful farrago that is bhel-puri chaat.

(This appeared in the print edition as "Bol Bachchan")

(Views expressed are personal)

Gautam Pemmaraju is a bombay-based writer, filmmaker & researcher