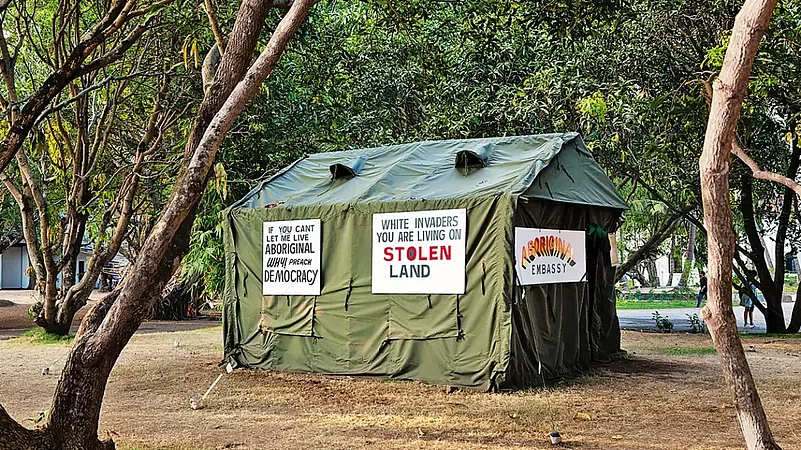

‘White Invaders You Are Living On Stolen Land’. These words are written in bold with black and red ink on a tent made of canvas. This installation—called ‘Aboriginal Embassy’—has been created by putting up a tent outside the main Biennale venue in Fort Kochi by Australian aboriginal artist Richard Bell, 70.

Constituted of different videos, installations and paintings, this tent stands in the face of the ruling classes across the world who have denied dues to the indigenous people. One of the posters pasted on the tent reads: ‘If You Can’t Let Me Live Aboriginal Why Preach Democracy’. This tent is a symbol of neglect, distance and dispossession.

The concept of ‘Aboriginal Embassy’ is rooted in the long movement that has been ongoing in front of the Old Parliament building at Canberra, Australia for more than 50 years.

At the peak of the black rights movement across the United States and the other parts of the world, Australian indigenous activists like Michael Anderson, Billy Craigie, Bertie Williams and Tony Coorey left their base in Redfern and reached Canberra. In 1972, on January 26—celebrated as Australia Day—they planted a beach umbrella in front of the Parliament building with a sign that read: ‘Aboriginal Embassy’. By calling it an Embassy these activists tried to make it clear that they neither had an engagement or deal with the Crown, nor had they ceded their land to them.

“If the aboriginals open an embassy in their own land to express their strong displeasure, can they be blamed? The embassy has been taken up as a symbol reflecting the pitiful condition of aboriginals at an international level,” says Bell, who considers his art a form of activism.

Seeking Solidarity

An integrated constituent of the indigenous rights movement, Bell’s work questions the authority and moral of the colonisers who have taken over their lands. His tent that has been roaming around the world since 2013, seeks solidarity of all the indigenous people across the world. One of his most famous paintings titled ‘Immigration Policy’ (2017) reads, ‘YOU CAN GO NOW’, in bold. These unapologetically assertive words pop out from the map of Australia that is whitewashed with a black background.

Bell has been calling for the restoration of indigenous rights for more than three decades. While talking to The Guardian newspaper he said: “We need a new constitution for a new republic.” He feels the exchange of money and land is the only thing that can ‘reset’ the whole system. “There’s got to be a day of reckoning. Exchanges of money and land cannot be avoided. Until then, we’re never going to say that you (non-indigenous people) belong here. You won’t be able to say that until we say you can,” Bell told The Guardian in an interview.

Reflection of his demands that the indigenous people must be paid back and only then they would decide whether to let the colonisers stay could be found in his work titled ‘Pay the Rent’. A digital board shows the ongoing and increasing debts of the Australian government to the indigenous people.

Bell’s works have never been received well by the white Australian elite artist groups. In 2019, he wanted to take the tent to the Venice Biennale. However, his proposals were not accepted perhaps due to the critique of the inner functions of the art world. “My proposal was critiquing the processes and inner workings of the art world. That’s what I do,” says Bell. As he was not allowed to present his work, he gate-crashed and took a replica of the Australian pavilion bounded in chains and pushed it into a canal on a barge.

‘Aboriginal Art is a White Thing’

Born in 1953 in Charleville, Queensland, he grew up amid extreme poverty. His childhood was spent waiting for the white men to throw corrugated irons to them. These were the constituents they used for making tin shacks. In 1968, after the historic referendum that gave the Commonwealth the power to make laws for the aboriginal people of the land, bulldozers were sent to demolish his house. They were moved to a house that was inhabitable.

Bell’s activism and life, however, changed when he landed in Redfern, the then boiling spot of the black rights movement. Since then, he started working with different activist organisations. Later, he also collaborated with the Black Panther member Emory Douglas, who is an American graphic artist.

One of the major artistic statements of Bell is the Bell’s theorem. It reads: ‘Aboriginal Art is a White Thing’. This assertive statement that he made in 2002 dominated his art works and the collaborative efforts he took up after that.

In 2003, he, along with a few other artists, started proppaNow—an artists’ collective that trains and gives space to aboriginal artists. However, Bell thinks that this Brisbane-based collective actually teaches collaboration. “The power of the collective is always greater than the sum of its parts. And we use that to assert ourselves into the Australian art scene,” says Bell.

This idea of collective came from his childhood experience. He used to see how the migrant workers coming from the city were asked for money by the villagers. “One of the men would come back from work and they’d be all cashed up. And, of course, everybody would borrow money from them. The first thing that the woman in the family would have to do is go and pay back all the people who lent her money when their husbands came home!” Bell told the National Indigenous Television.

The collective living and building of solidarity drove him to work as an activist-artist. The recent documentary titled ‘You Can Go Now’ that features Bell’s life and works rightly portrays him as he wants to be self-described—an ‘activist masquerading as an artist’. The cry of Bell perhaps could be better heard in the words of a poet from his own land, Zelda Quakawoot:

A right to be heard

Not censored of word

A voice that is true

Not a momentary view

A word that is said

It remains in our heads

Of value that’s true

In both me and you

It signals the start

From deep in our hearts

A sentence recalls

From the big to the small

It flows like a stream…

“I have a dream...”

(This appeared in the print edition as "THE TENT OF RESISTANCE")